The Failure of Democratic Storytelling

Economist James Kwak on Free-Market Mythmaking and 'Economism'

The lesson of November 8, according to many, is that Democrats need a better electoral message for “white, working-class” voters in the Upper Midwest. That is too narrow a conclusion. The broader lesson is that the Democratic Party needs a new economic vision.

It was a close election. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote handily and only lost the presidency by about 110,000 votes in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. But Donald Trump’s victory exposed a problem that existed regardless of the Electoral College tally: Democrats do not have a coherent economic story that can appeal to people on the wrong side of the growing inequality divide. People who think their financial situation is worse than four years ago voted for Trump by an astounding 78-19 margin.

The underlying historical problem is that, since the early days of Bill Clinton’s administration, Democrats have been chasing Republicans when it comes to economic issues. The Republican Party’s economic vision can be expressed in two words: free markets. Beginning in the 1950s, Milton Friedman and other prominent economists transformed the abstract models of Economics 101—in which competitive markets, driven by supply and demand, produce the best of all possible worlds—into a universal framework for interpreting social reality. This worldview, which I call economism, became the default economic handbook for the conservative movement and the Republican Party. It brilliantly fulfilled the crucial role of any ideology: it made the interests of a class—businesses and the wealthy—appear identical to the interests of society as a whole.

From the inauguration of Ronald Reagan in 1981, Republicans’ embrace of introductory economics put Democrats at an ideological disadvantage. The rhetoric of economism is simple and compelling: competitive markets maximize social welfare, so well-meaning government policies—welfare, regulation, even Social Security—only make people worse off. (And, if you don’t agree, you just don’t understand economics.) The solution to any problem is to unleash the forces of free enterprise and innovation. By comparison, the Democrats’ economic vision was an unsatisfying jumble of social insurance, industrial policy, consumer protection, welfare, and fiscal stimulus.

Bill Clinton tried to solved this problem—by making the Democrats the other free market party. To Reagan’s diagnosis, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” Clinton responded with the cure: “The era of big government is over.” Confronted by Newt Gingrich’s increasingly radical Republican Party, Clinton positioned himself as the responsible steward of the markets—reducing budget deficits, ratifying NAFTA, enacting welfare reform, cutting capital gains taxes, repealing the Glass-Steagall Act, and signing off on the non-regulation of derivatives. Politically, his party was rewarded by a major increase in contributions from the corporate sector, particularly Wall Street, which gave them the firepower to remain competitive in national elections.

As Democrats internalized the vocabulary of economism, however, they increasingly conceded the battle of ideas to their rivals. While Republicans ritualistically invoke the magic of supply and demand, Democrats are stuck with “me, too” messaging: We also love markets, only we want to make them work even better by correcting for “market failures.” One story is simple: freedom and competition create prosperity; government intervention kills jobs. The other is complicated: government programs are necessary to fix market imperfections.

This pattern continued under President Obama, who governed as an economic technocrat. Obama embraced the Trans-Pacific Partnership on the textbook grounds that more trade is good for everyone. The Dodd-Frank Act attempted to fix the financial system by mandating hundreds of new rules to carefully prune risks and improve market functioning. Even Obamacare, the president’s signature achievement, relies on market forces to expand health coverage, following a blueprint laid down by the conservative Heritage Foundation and adopted by Mitt Romney in Massachusetts.

As economics, it is true that market failures can be mitigated by government action. But as politics, “impose an individual mandate to correct for adverse selection by forcing the healthy to subsidize the sick” isn’t much of a rallying cry. Democratic policies have often offered little to families struggling to make ends meet. And when they have helped the working class—Medicaid expansion and the Obamacare health insurance subsidies, for example—the lack of a compelling economic story has ensured that Democrats get little political benefit.

After two decades of promising that markets (properly regulated) will take care of everyone, it is little wonder that Democrats have lost credit with people who feel worse off in the age of globalization and technology. To restore that credit, the party needs more than smart policies, which Hillary Clinton offered by the dozen. Democrats need to reach back to their forefathers, past John Kennedy—who famously said that “a rising tide lifts all boats”—to Franklin Roosevelt. It was Roosevelt, in the “Four Freedoms” speech, who recognized that the strength of our democracy depends on its ability to fulfill citizens’ basic expectations, including: “equality of opportunity for youths and others; jobs for those who can work; security for those who need it; [and] the ending of special privilege for the few.”

The genius of economism is to disguise a political ideology—shrink government, deregulate markets, and let the chips fall where they may—as an abstract, value-neutral description of the world. If Democrats want to reclaim their heritage as the party of working men and women, they need an alternative economic vision, one centered on jobs, security, and fairness—not smoothly humming markets that will magically make everyone better off.

This does not mean abandoning sensible economic policy. In many contexts, free competition is the best way to create jobs and ensure fair outcomes. But we also need structural constraints on the financial system to reduce the risk of cataclysmic crises, strong unions to ensure the bargaining power of workers, and robust social insurance programs to protect people against the risks of severe illness, disability, and unemployment. Competitive markets should be one means to the end of broadly shared prosperity—not an end in themselves.

Franklin Roosevelt knew what people want: to work at a decent job, to have protection against unforeseen catastrophes, and to be treated fairly. That is the future that Democrats need to offer to working families left behind in our new age of inequality.

James Kwak’s latest, Economism, is available tomorrow from Pantheon.

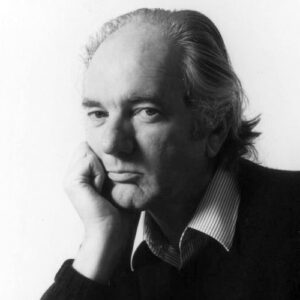

James Kwak

James Kwak is a professor at the University of Connecticut School of Law and the co-author, with Simon Johnson, of 13 Bankers and White House Burning. He has a Ph.D. in intellectual history from UC Berkeley and a J.D. from the Yale Law School. Before going to law school, he worked in the business world as a management consultant and a software entrepreneur.