I used to go to thrift stores with my friends. We’d take the train into Boston, and go to The Garment District, which is this huge vintage clothing warehouse. Everything is arranged by color, and somehow that makes all of the clothes beautiful. It’s kind of like if you went through the wardrobe in the Narnia books, only instead of finding Aslan and the White Witch and horrible Eustace, you found this magic clothing world—instead of talking animals, there were feather boas and wedding dresses and bowling shoes, and paisley shirts and Doc Martens and everything hung up on racks so that first you have black dresses, all together, like the world’s largest indoor funeral, and then blue dresses—all the blues you can imagine—and then red dresses and so on. Pink reds and orangey reds and purple reds and exit-light reds and candy reds. Sometimes I would close my eyes and Natasha and Natalie and Jake would drag me over to a rack, and rub a dress against my hand. “Guess what color this is.”

We had this theory that you could learn how to tell, just by feeling, what color something was. For example, if you’re sitting on a lawn, you can tell what color green the grass is, with your eyes closed, depending on how silky-rubbery it feels. With clothing, stretchy velvet stuff always feels red when your eyes are closed, even if it’s not red. Natasha was always best at guessing colors, but Natasha is also best at cheating at games and not getting caught.

One time we were looking through kids’ T-shirts and we found a Muppets T-shirt that had belonged to Natalie in third grade. We knew it belonged to her, because it still had her name inside, where her mother had written it in permanent marker when Natalie went to summer camp. Jake bought it back for her, because he was the only one who had money that weekend. He was the only one who had a job.

Maybe you’re wondering what a guy like Jake is doing in The Garment District with a bunch of girls. The thing about Jake is that he always has a good time, no matter what he’s doing. He likes everything, and he likes everyone, but he likes me best of all. Wherever he is now, I bet he’s having a great time and wondering when I’m going to show up. I’m always running late. But he knows that.

We had this theory that things have life cycles, the way that people do. The life cycle of wedding dresses and feather boas and T-shirts and shoes and handbags involves The Garment District. If clothes are good, or even if they’re bad in an interesting way, The Garment District is where they go when they die. You can tell that they’re dead, because of the way that they smell. When you buy them, and wash them, and start wearing them again, and they start to smell like you, that’s when they reincarnate. But the point is, if you’re looking for a particular thing, you just have to keep looking for it. You have to look hard.

Down in the basement at The Garment District they sell clothing and beat-up suitcases and teacups by the pound. You can get eight pounds’ worth of prom dresses—a slinky black dress, a poufy lavender dress, a swirly pink dress, a silvery, starry lamé dress so fine you could pass it through a key ring—for eight dollars. I go there every week, hunting for Grandmother Zofia’s faery handbag.

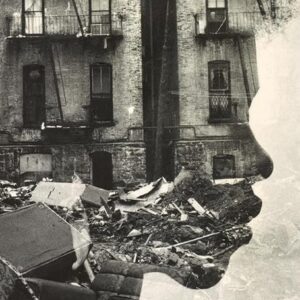

The faery handbag: It’s huge and black and kind of hairy. Even when your eyes are closed, it feels black. As black as black ever gets, like if you touch it, your hand might get stuck in it, like tar or black quicksand or when you stretch out your hand at night, to turn on a light, but all you feel is darkness.

Fairies live inside it. I know what that sounds like, but it’s true.

Grandmother Zofia said it was a family heirloom. She said that it was over two hundred years old. She said that when she died, I had to look after it. Be its guardian. She said that it would be my responsibility.

I said that it didn’t look that old, and that they didn’t have handbags two hundred years ago, but that just made her cross. She said, “So then tell me, Genevieve, darling, where do you think old ladies used to put their reading glasses and their heart medicine and their knitting needles?”

I know that no one is going to believe any of this. That’s okay. If I thought you would, then I couldn’t tell you. Promise me that you won’t believe a word. That’s what Zofia used to say to me when she told me stories. At the funeral, my mother said, half-laughing and half-crying, that her mother was the world’s best liar. I think she thought maybe Zofia wasn’t really dead. But I went up to Zofia’s coffin, and I looked her right in the eyes. They were closed. The funeral parlor had made her up with blue eyeshadow, and blue eyeliner. She looked like she was going to be a news anchor on Fox television, instead of dead. It was creepy and it made me even sadder than I already was. But I didn’t let that distract me.

“Okay, Zofia,” I whispered. “I know you’re dead, but this is important. You know exactly how important this is. Where’s the handbag? What did you do with it? How do I find it? What am I supposed to do now?”

Of course, she didn’t say a word. She just lay there, this little smile on her face, as if she thought the whole thing—death, blue eyeshadow, Jake, the handbag, fairies, Scrabble, Baldeziwurlekistan, all of it—was a joke. She always did have a weird sense of humor. That’s why she and Jake got along so well.

I grew up in a house next door to the house where my mother lived when she was a little girl. Her mother, Zofia Swink, my grandmother, babysat me while my mother and father were at work.

Zofia never looked like a grandmother. She had long black hair, which she plaited up in spiky towers. She had large blue eyes. She was taller than my father. She looked like a spy or ballerina or a lady pirate or a rock star. She acted like one too. For example, she never drove anywhere. She rode a bike. It drove my mother crazy. “Why can’t you act your age?” she’d say, and Zofia would just laugh.

Zofia and I played Scrabble all the time. Zofia always won, even though her English wasn’t all that great, because we’d decided that she was allowed to use Baldeziwurleki vocabulary. Baldeziwurlekistan is where Zofia was born, over two hundred years ago. That’s what Zofia said. (My grandmother claimed to be over two hundred years old. Or maybe even older. Sometimes she claimed that she’d even met Genghis Khan. He was much shorter than her. I probably don’t have time to tell that story.) Baldeziwurlekistan is also an incredibly valuable word in Scrabble points, even though it doesn’t exactly fit on the board. Zofia put it down the first time we played. I was feeling pretty good because I’d gotten forty-one points for zippery on my turn.

Zofia kept rearranging her letters on her tray. Then she looked over at me, as if daring me to stop her, and put down eziwurlekistan, after bald. She used delicious, zippery, wishes, kismet, and needle, and made to into toe. Baldeziwurlekistan went all the way across the board and then trailed off down the righthand side.

I started laughing.

“I used up all my letters,” Zofia said. She licked her pencil and started adding up points.

“That’s not a word,” I said. “Baldeziwurlekistan is not a word. Besides, you can’t do that. You can’t put an eighteen-letter word on a board that’s fifteen squares across.”

“Why not? It’s a country,” Zofia said. “It’s where I was born, little darling.”

“Challenge,” I said. I went and got the dictionary and looked it up. “There’s no such place.”

“Of course there isn’t nowadays,” Zofia said. “It wasn’t a very big place, even when it was a place. But you’ve heard of Samarkand, and Uzbekistan and the Silk Road and Genghis Khan. Haven’t I told you about meeting Genghis Khan?”

I looked up Samarkand. “Okay,” I said. “Samarkand is a real place. A real word. But Baldeziwurlekistan isn’t.”

“They call it something else now,” Zofia said. “But I think it’s important to remember where we come from. I think it’s only fair that I get to use Baldeziwurleki words. Your English is so much better than me. Promise me something, mouthful of dumpling, a small, small thing. You’ll remember its real name. Baldeziwurlekistan. Now when I add it up, I get three hundred and sixty-eight points. Could that be right?”

If you called the faery handbag by its right name, it would be something like orzipanikanikcz, which means the “bag of skin where the world lives,” only Zofia never spelled that word the same way twice. She said you had to spell it a little differently each time. You never wanted to spell it exactly the right way, because that would be dangerous.

I called it the faery handbag because I put faery down on the Scrabble board once. Zofia said that you spelled it with an i, not an e. She looked it up in the dictionary, and lost a turn.

Zofia said that in Baldeziwurlekistan they used a board and tiles for divination, prognostication, and sometimes even just for fun. She said it was a little like playing Scrabble. That’s probably why she turned out to be so good at Scrabble. The Baldeziwurlekistanians used their tiles and board to communicate with the people who lived under the hill. The people who lived under the hill knew the future. The Baldeziwurlekistanians gave them fermented milk and honey, and the young women of the village used to go and lie out on the hill and sleep under the stars. Apparently the people under the hill were pretty cute. The important thing was that you never went down into the hill and spent the night there, no matter how cute the guy from under the hill was. If you did, even if you spent only a single night under the hill, when you came out again, a hundred years might have passed. “Remember that,” Zofia said to me. “It doesn’t matter how cute a guy is. If he wants you to come back to his place, it isn’t a good idea. It’s okay to fool around, but don’t spend the night.”

Every once in a while, a woman from under the hill would marry a man from the village, even though it never ended well. The problem was that the women under the hill were terrible cooks. They couldn’t get used to the way time worked in the village, which meant that supper always got burnt, or else it wasn’t cooked long enough. But they couldn’t stand to be criticized. It hurt their feelings. If their village husband complained, or even if he looked like he wanted to complain, that was it. The woman from under the hill went back to her home, and even if her husband went and begged and pleaded and apologized, it might be three years or thirty years or a few generations before she came back out.

Even the best, happiest marriages between the Baldeziwurlekistanians and the people under the hill fell apart when the children got old enough to complain about dinner. But everyone in the village had some hill blood in them.

“It’s in you,” Zofia said, and kissed me on the nose. “Passed down from my grandmother and her mother. It’s why we’re so beautiful.”

When Zofia was nineteen, the shaman-priestess in her village threw the tiles and discovered that something bad was going to happen. A raiding party was coming. There was no point in fighting them. They would burn down everyone’s houses and take the young men and women for slaves. And it was even worse than that. There was going to be an earthquake as well, which was bad news because usually, when raiders showed up, the village went down under the hill for a night and when they came out again, the raiders would have been gone for months or decades or even a hundred years. But this earthquake was going to split the hill right open.

The people under the hill were in trouble. Their home would be destroyed, and they would be doomed to roam the face of the earth, weeping and lamenting their fate until the sun blew out and the sky cracked and the seas boiled and the people dried up and turned to dust and blew away. So the shaman-priestess went and divined some more, and the people under the hill told her to kill a black dog and skin it and use the skin to make a purse big enough to hold a chicken, an egg, and a cooking pot. So she did, and then the people under the hill made the inside of the purse big enough to hold all of the village and all of the people under the hill and mountains and forests and seas and rivers and lakes and orchards and a sky and stars and spirits and fabulous monsters and sirens and dragons and dryads and mermaids and beasties and all the little gods that the Baldeziwurlekistanians and the people under the hill worshipped.

“Your purse is made out of dog skin?” I said. “That’s disgusting!”

“Little dear pet,” Zofia said, looking wistful. “Dog is delicious. To Baldeziwurlekistanians, dog is a delicacy.”

Before the raiding party arrived, the village packed up all of their belongings and moved into the handbag. The clasp was made out of bone. If you opened it one way, then it was just a purse big enough to hold a chicken and an egg and a clay cooking pot, or else a pair of reading glasses and a library book and a pillbox. If you opened the clasp another way, then you found yourself in a little boat floating at the mouth of a river. On either side of you was forest, where the Baldeziwurlekistanian villagers and the people under the hill made their new settlement.

If you opened the handbag the wrong way, though, you found yourself in a dark land that smelled like blood. That’s where the guardian of the purse (the dog whose skin had been sewn into a purse) lived. The guardian had no skin. Its howl made blood come out of your ears and nose. It tore apart anyone who turned the clasp in the opposite direction and opened the purse in the wrong way.

“Here is the wrong way to open the handbag,” Zofia said. She twisted the clasp, showing me how she did it. She opened the mouth of the purse, but not very wide, and held it up to me. “Go ahead, darling, and listen for a second.”

I put my head near the handbag, but not too near. I didn’t hear anything. “I don’t hear anything,” I said.

“The poor dog is probably asleep,” Zofia said. “Even nightmares have to sleep now and then.”

After he got expelled, everybody at school called Jake Houdini instead of Jake. Everybody except for me. I’ll explain why, but you have to be patient. It’s hard work telling everything in the right order.

Jake is smarter and also taller than most of our teachers. Not quite as tall as me. We’ve known each other since third grade. Jake has always been in love with me. He says he was in love with me even before third grade, even before we ever met. It took me a while to fall in love with Jake.

In third grade, Jake knew everything already, except how to make friends. He used to follow me around all day long. It made me so mad that I kicked him in the knee. When that didn’t work, I threw his backpack out the window of the school bus. That didn’t work either, but the next year Jake took some tests and the school decided that he could skip fourth and fifth grade. Even I felt sorry for Jake then. Sixth grade didn’t work out. When the sixth graders wouldn’t stop flushing his head down the toilet, he went out and caught a skunk and set it loose in the boys’ locker room.

The school was going to suspend him for the rest of the year, but instead Jake took two years off while his mother homeschooled him. He learned Latin and Hebrew and Greek, how to write sestinas, how to make sushi, how to play bridge, and even how to knit. He learned fencing and ballroom dancing. He worked in a soup kitchen and made a Super 8 movie about Civil War reenactors who play extreme croquet in full costume instead of firing off cannons. He started learning how to play guitar. He even wrote a novel. I’ve never read it—he says it was awful.

When he came back two years later, because his mother had cancer for the first time, the school put him back with our year, in seventh grade. He was still way too smart, but he was finally smart enough to figure out how to fit in. Plus he was good at soccer and he was yummy. Did I mention that he played guitar? Every girl in school had a crush on Jake, but he used to come home after school with me and play Scrabble with Zofia and ask her about Baldeziwurlekistan.

Jake’s mom was named Cynthia. She collected ceramic frogs and knock-knock jokes. When we were in ninth grade, she had cancer again. When she died, Jake smashed all of her frogs. That was the first funeral I ever went to. A few months later, Jake’s father asked Jake’s fencing teacher out on a date. They got married right after the school expelled Jake for his AP project on Houdini. That was the first wedding I ever went to. Jake and I stole a bottle of wine and drank it, and I threw up in the swimming pool at the country club. Jake threw up all over my shoes.

So, anyway, the village and the people under the hill lived happily ever after for a few weeks in the handbag, which they had tied around a rock in a dry well that the people under the hill had determined would survive the earthquake. But some of the Baldeziwurlekistanians wanted to come out again and see what was going on in the world. Zofia was one of them. It had been summer when they went into the bag, but when they came out again, and climbed out of the well, snow was falling and their village was ruins and crumbly old rubble. They walked through the snow, Zofia carrying the handbag, until they came to another village, one that they’d never seen before. Everyone in that village was packing up their belongings and leaving, which gave Zofia and her friends a bad feeling. It seemed to be just the same as when they went into the handbag.

They followed the refugees, who seemed to know where they were going, and finally everyone came to a city. Zofia had never seen such a place. There were trains and electric lights and movie theaters, and there were people shooting each other. Bombs were falling. A war going on. Most of the villagers decided to climb right back inside the handbag, but Zofia volunteered to stay in the world and look after the handbag. She had fallen in love with movies and silk stockings and with a young man, a Russian deserter.

Zofia and the Russian deserter married and had many adventures and finally came to America, where my mother was born. Now and then Zofia would consult the tiles and talk to the people who lived in the handbag and they would tell her how best to avoid trouble and how she and her husband could make some money. Every now and then one of the Baldeziwurlekistanians or one of the people from under the hill came out of the handbag and wanted to go grocery shopping, or to a movie or an amusement park to ride on roller coasters, or to the library.

The more advice Zofia gave her husband, the more money they made. Her husband became curious about Zofia’s handbag, because he could see that there was something odd about it, but Zofia told him to mind his own business. He began to spy on Zofia, and saw that strange men and women were coming in and out of the house. He became convinced that either Zofia was a spy for the Communists, or maybe that she was having affairs. They fought and he drank more and more, and finally he threw away her divination tiles. “Russians make bad husbands,” Zofia told me. Finally, one night while Zofia was sleeping, her husband opened the bone clasp and climbed inside the handbag.

“I thought he’d left me,” Zofia said. “For almost twenty years I thought he’d left me and your mother and taken off for California. Not that I minded. I was tired of being married and cooking dinners and cleaning house for someone else. It’s better to cook what I want to eat, and clean up when I decide to clean up. It was harder on your mother, not having a father. That was the part that I minded most.

“Then it turned out that he hadn’t run away after all. He spent one night in the handbag and came out again twenty years later, exactly as handsome as I remembered, and enough time had passed that I had forgiven him all the quarrels. We made up and it was all very romantic and then when we had another fight the next morning, he went and kissed your mother, who had slept right through his visit, on the cheek, and then he climbed right back inside the handbag. I didn’t see him again for another twenty years. The last time he showed up, we went to see Star Wars and he liked it so much that he went back inside the handbag to tell everyone else about it. In a couple of years they’ll all show up and want to see it on video and all of the sequels too.”

“Tell them not to bother with the prequels,” I said.

The thing about Zofia and libraries is that she’s always losing library books. She says that she hasn’t lost them, and in fact that they aren’t even overdue, really. It’s just that even one week inside the faery handbag is a lot longer in library-world time. So what is she supposed to do about it? The librarians all hate Zofia. She’s banned from using any of the branches in our area. When I was eight, she got me to go to the library for her and check out biographies and science books and Georgette Heyer romance novels. My mother was livid when she found out, but it was too late. Zofia had already misplaced most of them.

It’s really hard to write about somebody as if they’re really dead. I still think Zofia must be sitting in her living room, in her house, watching some old horror movie, dropping popcorn into her handbag. She’s waiting for me to come over and play Scrabble.

Nobody is ever going to return those library books now.

My mother used to come home from work and roll her eyes. “Have you been telling them your fairy stories?” she’d say. “Genevieve, your grandmother is a horrible liar.”

Zofia would fold up the Scrabble board and shrug at me and Jake. “I’m a wonderful liar,” she’d say. “I’m the best liar in the world. Promise me you won’t believe a single word.”

But she wouldn’t tell the story of the faery handbag to Jake. Only the old Baldeziwurlekistanian folktales and fairy tales about the people under the hill. She told him about how she and her husband made it all the way across Europe, hiding in haystacks and in barns. What she told me was how once, when her husband went off to find food, a farmer found her hiding in his chicken coop and tried to rape her. But she opened up the faery handbag in the way she showed me, and the dog came out and ate the farmer and all his chickens too.

She was teaching Jake and me how to curse in Baldeziwurleki. I also know how to say I love you, but I’m not going to ever say it to anyone again, except to Jake, when I find him.

When I was eight, I believed everything Zofia told me. By the time I was thirteen, I didn’t believe a single word. When I was fifteen, I saw a man come out of her house and get on Zofia’s three-speed bicycle and ride down the street. He wore funny clothes. He was a lot younger than my mother and father, and even though I’d never seen him before, he was familiar. I followed him on my bike, all the way to the grocery store. I waited just past the checkout lanes while he bought peanut butter, Jack Daniel’s, half a dozen instant cameras, and at least sixty packs of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, three bags of Hershey’s Kisses, a handful of Milky Way bars, and other stuff from the rack of checkout candy. While the checkout clerk was helping him bag up all of that chocolate, he looked up and saw me. “Genevieve?” he said. “That’s your name, right?”

I turned and ran out of the store. He grabbed up the bags and ran after me. I don’t even think he got his change back. I was still running away, and then one of the straps on my flip-flops popped out of the sole, the way they do, and that made me really angry so I just stopped. I turned around.

“Who are you?” I said.

But I already knew. He looked like he could have been my mom’s younger brother. He was really cute. I could see why Zofia had fallen in love with him.

His name was Rustan. Zofia told my parents that he was an expert in Baldeziwurlekistanian folklore who would be staying with her for a few days. She brought him over for dinner. Jake was there too, and I could tell that Jake knew something was up. Everybody except my dad knew something was going on.

“You mean Baldeziwurlekistan is a real place?” my mother asked Rustan. “My mother is telling the truth?”

I could see that Rustan was having a hard time with that one. He obviously wanted to say that his wife was a horrible liar, but then where would he be? Then he couldn’t be the person that he was supposed to be.

There were probably a lot of things that he wanted to say. What he said was, “This is really good pizza.”

Rustan took a lot of pictures at dinner. The next day I went with him to get the pictures developed. He’d brought back some film with him, with pictures he’d taken inside the faery handbag, but those didn’t come out well. Maybe the film was too old. We got doubles of the pictures from dinner so that I could have some too. There’s a great picture of Jake, sitting outside on the porch. He’s laughing, and he has his hand up to his mouth, like he’s going to catch the laugh. I have that picture up on my computer, and also up on my wall over my bed.

I bought a Cadbury Creme Egg for Rustan. Then we shook hands and he kissed me once on each cheek. “Give one of those kisses to your mother,” he said, and I thought about how the next time I saw him, I might be Zofia’s age, and he would be only a few days older. The next time I saw him, Zofia would be dead. Jake and I might have kids. That was too weird.

I know Rustan tried to get Zofia to go back with him, to live in the handbag, but she wouldn’t.

“It makes me dizzy in there,” she used to tell me. “And they don’t have movie theaters. And I have to look after your mother and you. Maybe when you’re old enough to look after the handbag, I’ll poke my head inside, just long enough for a little visit.”

* * * *

I didn’t fall in love with Jake because he was smart. I’m pretty smart myself. I know that smart doesn’t mean nice, or even mean that you have a lot of common sense. Look at all the trouble smart people get themselves into.

I didn’t fall in love with Jake because he could make maki rolls and had a black belt in fencing, or whatever it is that you get if you’re good in fencing. I didn’t fall in love with Jake because he plays guitar. He’s a better soccer player than he is a guitar player.

Those were the reasons why I went out on a date with Jake. That, and because he asked me. He asked if I wanted to go see a movie, and I asked if I could bring my grandmother and Natalie and Natasha. He said sure and so all five of us sat and watched Bring It On and every once in a while Zofia dropped a couple of Milk Duds or some popcorn into her purse. I don’t know if she was feeding the dog, or if she’d opened the purse the right way, and was throwing food at her husband.

I fell in love with Jake because he told stupid knock-knock jokes to Natalie, and told Natasha that he liked her jeans. I fell in love with Jake when he took me and Zofia home. He walked her up to her front door and then he walked me up to mine. I fell in love with Jake when he didn’t try to kiss me. The thing is, I was nervous about the whole kissing thing. Most guys think that they’re better at it than they really are. Not that I think I’m a real genius at kissing either, but I don’t think kissing should be a competitive sport. It isn’t tennis.

Natalie and Natasha and I used to practice kissing with each other. Just for practice. We got pretty good at it. We could see why kissing was supposed to be fun.

But Jake didn’t try to kiss me. Instead he just gave me this really big hug. He put his face in my hair and he sighed. We stood there like that, and then finally I said, “What are you doing?”

“I just wanted to smell your hair,” he said.

“Oh,” I said. That made me feel weird, but in a good way. I stuck my nose in his hair, which is brown and curly. I smelled it. We stood there and smelled each other’s hair, and I felt so good. I felt so happy.

Jake said into my hair, “Do you know that actor John Cusack?”

I said, “Yeah. One of Zofia’s favorite movies is Better Off Dead. We watch it all the time.”

“So he likes to go up to women and smell their armpits.”

“Gross!” I said. “That’s such a lie! What are you doing now? That tickles.”

“I’m smelling your ear,” Jake said.

Jake’s hair smelled like iced tea with honey in it, after all the ice has melted.

Kissing Jake is like kissing Natalie or Natasha, except that it isn’t just for fun. It feels like something there isn’t a word for in Scrabble.

The deal with Houdini is that Jake got interested in him during Advanced Placement American History. He and I were both put in tenth-grade history. We were doing biography projects. I was studying Joseph McCarthy. My grandmother had all sorts of stories about McCarthy. She hated him for what he did to Hollywood.

Jake didn’t turn in his project—instead he told everyone in our AP class except for Mr. Streep (we call him Meryl) to meet him at the gym on Saturday. When we showed up, Jake reenacted one of Houdini’s escapes with a laundry bag, handcuffs, a gym locker, bicycle chains, and the school’s swimming pool. It took him three and a half minutes to get free, and this guy named Roger took a bunch of photos and then put the photos online. One of the photos ended up in The Boston Globe, and Jake got expelled. The really ironic thing was that while his mom was in the hospital, Jake had applied to MIT. He did it for his mom. He thought that way she’d have to stay alive. She was so excited about MIT. A couple of days after he’d been expelled, right after the wedding, while his dad and the fencing instructor were in Bermuda, he got an acceptance letter in the mail and a phone call from this guy in the admissions office who explained why they had to withdraw the acceptance.

My mother wanted to know why I let Jake wrap himself up in bicycle chains and then watched while Peter and Michael pushed him into the deep end of the school pool. I said that Jake had a backup plan. Ten more seconds and we were all going to jump into the pool and open the locker and get him out of there. I was crying when I said that. Even before he got in the locker, I knew how stupid Jake was being. Afterwards, he promised me that he’d never do anything like that again.

That was when I told him about Zofia’s husband, Rustan, and about Zofia’s handbag. How stupid am I?

So I guess you can figure out what happened next. The problem is that Jake believed me about the handbag. We spent a lot of time over at Zofia’s, playing Scrabble. Zofia never let the faery handbag out of her sight. She even took it with her when she went to the bathroom. I think she even slept with it under her pillow.

I didn’t tell her that I’d said anything to Jake. I wouldn’t ever have told anybody else about it. Not Natasha. Not even Natalie, who is the most responsible person in all of the world. Now, of course, if the handbag turns up and Jake still hasn’t come back, I’ll have to tell Natalie. Somebody has to keep an eye on the stupid thing while I go find Jake.

What worries me is that maybe one of the Baldeziwurlekistanians or one of the people under the hill or maybe even Rustan popped out of the handbag to run an errand and got worried when Zofia wasn’t there. Maybe they’ll come looking for her and bring it back. Maybe they know I’m supposed to look after it now. Or maybe they took it and hid it somewhere. Maybe someone turned it in at the lost-and-found at the library and that stupid librarian called the FBI. Maybe scientists at the Pentagon are examining the handbag right now. Testing it. If Jake comes out, they’ll think he’s a spy or a superweapon or an alien or something. They’re not going to just let him go.

Everyone thinks Jake ran away, except for my mother, who is convinced that he was trying out another Houdini escape and is probably lying at the bottom of a lake somewhere. She hasn’t said that to me, but I can see her thinking it. She keeps making cookies for me.

What happened is that Jake said, “Can I see that for just a second?”

He said it so casually that I think he caught Zofia off guard. She was reaching into the purse for her wallet. We were standing in the lobby of the movie theater on a Monday morning. Jake was behind the snack counter. He’d gotten a job there. He was wearing this stupid red paper hat and some kind of apron bib thing. He was supposed to ask us if we wanted to supersize our drinks.

He reached over the counter and took Zofia’s handbag right out of her hand. He closed it and then he opened it again. I think he opened it the right way. I don’t think he ended up in the dark place. He said to me and Zofia, “I’ll be right back.” And then he wasn’t there anymore. It was just me and Zofia and the handbag, lying there on the counter where he’d dropped it.

If I’d been fast enough, I think I could have followed him. But Zofia had been guardian of the faery handbag for a lot longer. She snatched the bag back and glared at me. “He’s a very bad boy,” she said. She was absolutely furious. “You’re better off without him, Genevieve, I think.”

“Give me the handbag,” I said. “I have to go get him.”

“It isn’t a toy, Genevieve,” she said. “It isn’t a game. This isn’t Scrabble. He comes back when he comes back. If he comes back.”

“Give me the handbag,” I said. “Or I’ll take it from you.”

She held the handbag up high over her head, so that I couldn’t reach it. I hate people who are taller than me. “What are you going to do now?” Zofia said. “Are you going to knock me down? Are you going to steal the handbag? Are you going to go away and leave me here to explain to your parents where you’ve gone? Are you going to say good-bye to your friends? When you come out again, they will have gone to college. They’ll have jobs and babies and houses and they won’t even recognize you. Your mother will be an old woman and I will be dead.”

“I don’t care,” I said. I sat down on the sticky red carpet in the lobby and started to cry. Someone wearing a little metal name tag came over and asked if we were okay. His name was missy. Or maybe he was wearing someone else’s tag.

“We’re fine,” Zofia said. “My granddaughter has the flu.”

She took my hand and pulled me up. She put her arm around me and we walked out of the theater. We never even got to see the stupid movie. We never even got to see another movie together. I don’t ever want to go see another movie. The problem is, I don’t want to see unhappy endings. And I don’t know if I believe in the happy ones.

“I have a plan,” Zofia said. “I will go find Jake. You will stay here and look after the handbag.”

“You won’t come back either,” I said. I cried even harder. “Or if you do, I’ll be like a hundred years old and Jake will still be sixteen.”

“Everything will be okay,” Zofia said. I wish I could tell you how beautiful she looked right then. It didn’t matter if she was lying or if she actually knew that everything was going to be okay. The important thing was how she looked when she said it. She said, with absolute certainty, or maybe with all the skill of a very skillful liar, “My plan will work. First we go to the library, though. One of the people under the hill just brought back an Agatha Christie mystery, and I need to return it.”

“We’re going to the library?” I said. “Why don’t we just go home and play Scrabble for a while.” You probably think I was just being sarcastic here, and I was being sarcastic. But Zofia gave me a sharp look. She knew that if I was being sarcastic that my brain was working again. She knew that I knew she was stalling for time. She knew that I was coming up with my own plan, which was a lot like Zofia’s plan, except that I was the one who went into the handbag. How was the part I was working on.

“We could do that,” she said. “Remember, when you don’t know what to do, it never hurts to play Scrabble. It’s like reading the I Ching or tea leaves.”

“Can we please just hurry?” I said.

Zofia just looked at me. “Genevieve, we have plenty of time. If you’re going to look after the handbag, you have to remember that. You have to be patient. Can you be patient?”

“I can try,” I told her. I’m trying, Zofia. I’m trying really hard. But it isn’t fair. Jake is off having adventures and talking to talking animals, and who knows, learning how to fly and some beautiful three-thousand-year-old girl from under the hill is teaching him how to speak fluent Baldeziwurleki. I bet she lives in a house that runs around on chicken legs, and she tells Jake that she’d love to hear him play something on the guitar. Maybe you’ll kiss her, Jake, because she’s put a spell on you. But whatever you do, don’t go up into her house. Don’t fall asleep in her bed. Come back soon, Jake, and bring the handbag with you.

I hate those movies, those books, where some guy gets to go off and have adventures and meanwhile the girl has to stay home and wait. I’m a feminist. I subscribe to Bust magazine, and I watch Buffy reruns. I don’t believe in that kind of shit.

We hadn’t been in the library for five minutes before Zofia picked up a biography of Carl Sagan and dropped it in her purse. She was definitely stalling for time. She was trying to come up with a plan that would counteract the plan that she knew I was planning. I wondered what she thought I was planning. It was probably much better than anything I’d come up with.

“Don’t do that!” I said.

“Don’t worry,” Zofia said. “Nobody was watching.”

“I don’t care if nobody saw! What if Jake’s sitting there in the boat, or what if he was coming back and you just dropped it on his head!”

“It doesn’t work that way,” Zofia said. Then she said, “It would serve him right, anyway.”

That was when the librarian came up to us. She had a name tag on as well. I was so sick of people and their stupid name tags. I’m not even going to tell you what her name was. “I saw that,” the librarian said.

“Saw what?” Zofia said. She smiled down at the librarian, like she was Queen of the Library, and the librarian was a petitioner.

The librarian stared hard at her. “I know you,” she said, almost sounding awed, like she was a weekend bird-watcher who had just seen Bigfoot. “We have your picture on the office wall. You’re Ms. Swink. You aren’t allowed to check out books here.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Zofia said. She was at least two feet taller than the librarian. I felt a bit sorry for the librarian. After all, Zofia had just stolen a seven-day book. She probably wouldn’t return it for a hundred years. My mother has always made it clear that it’s my job to protect other people from Zofia. I guess I was Zofia’s guardian before I became the guardian of the handbag.

The librarian reached up and grabbed Zofia’s handbag. She was small but she was strong. She jerked the handbag and Zofia stumbled and fell back against a work desk. I couldn’t believe it. Everyone except for me was getting a look at Zofia’s handbag. What kind of guardian was I going to be?

“Genevieve,” Zofia said. She held my hand very tightly, and I looked at her. She looked wobbly and pale. She said, “I feel very bad about all of this. Tell your mother I said so.”

Then she said one last thing, but I think it was in Baldeziwurleki.

The librarian said, “I saw you put a book in here. Right here.” She opened the handbag and peered inside. Out of the handbag came a long, lonely, ferocious, utterly hopeless scream of rage. I don’t ever want to hear that noise again. Everyone in the library looked up. The librarian made a choking noise and threw Zofia’s handbag away from her. A little trickle of blood came out of her nose and a drop fell on the floor. What I thought at first was that it was just plain luck that the handbag was closed when it landed. Later on I was trying to figure out what Zofia said. My Baldeziwurleki isn’t very good, but I think she was saying something like “Figures. Stupid librarian. I have to go take care of that damn dog.” So maybe that’s what happened. Maybe Zofia sent part of herself in there with the skinless dog. Maybe she fought it and won and closed the handbag. Maybe she made friends with it. I mean, she used to feed it popcorn at the movies. Maybe she’s still in there.

What happened in the library was Zofia sighed a little and closed her eyes. I helped her sit down in a chair, but I don’t think she was really there anymore. I rode with her in the ambulance, when the ambulance finally showed up, and I swear I didn’t even think about the handbag until my mother showed up. I didn’t say a word. I just left her there in the hospital with Zofia, who was on a respirator, and I ran all the way back to the library. But it was closed. So I ran all the way back again, to the hospital, but you already know what happened, right? Zofia died. I hate writing that. My tall, funny, beautiful, book-stealing, Scrabble-playing, storytelling grandmother died.

But you never met her. You’re probably wondering about the handbag. What happened to it. I put up signs all over town, like Zofia’s handbag was some kind of lost dog, but nobody ever called.

So that’s the story so far. Not that I expect you to believe any of it. Last night Natalie and Natasha came over and we played Scrabble. They don’t really like Scrabble, but they feel like it’s their job to cheer me up. I won. After they went home, I flipped all the tiles upside-down and then I started picking them up in groups of seven. I tried to ask a question, but it was hard to pick just one. The words I got weren’t so great either, so I decided that they weren’t English words. They were Baldeziwurleki words.

Once I decided that, everything became perfectly clear. First I put down kirif which means “happy news,” and then I got a b, an o, an l, an e, another i, an s, and a z. So then I could make kirif into bolekirifisz, which could mean “the happy result of a combination of diligent effort and patience.”

I would find the faery handbag. The tiles said so. I would work the clasp and go into the handbag and have my own adventures and would rescue Jake. Hardly any time would have gone by before we came back out of the handbag. Maybe I’d even make friends with that poor dog and get to say good-bye, for real, to Zofia. Rustan would show up again and be really sorry that he’d missed Zofia’s funeral and this time he would be brave enough to tell my mother the whole story. He would tell her that he was her father. Not that she would believe him. Not that you should believe this story. Promise me that you won’t believe a word.

“The Faery Handbag” from MAGIC FOR BEGINNERS. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2004 by Kelly Link.