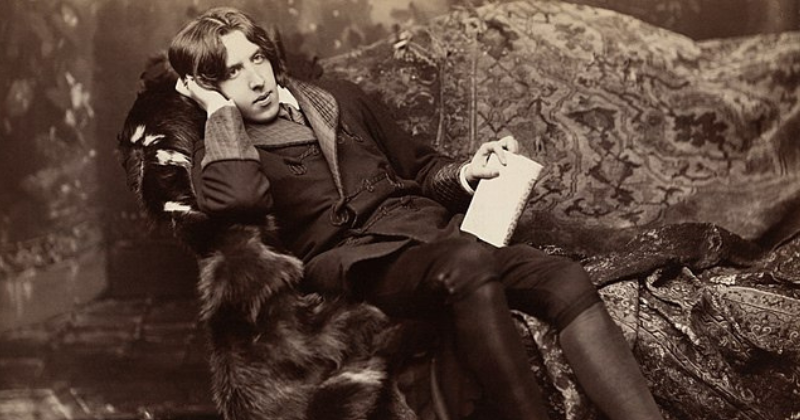

The Exile of Oscar Wilde, Dublin’s Charming Ghost

Alexander Poots on Northern Ireland's Literary Past

When still a boy, Forrest Reid saw Oscar Wilde in Belfast.

I beheld my first celebrity. Not that I knew him to be celebrated, but I could see for myself his appearance was remarkable. I had been taught that it was rude to stare, but on this occasion, though I was with my mother, I could not help staring, and even feeling I was intended to do so. He was, my mother told me, a Mr. Oscar Wilde.

Reid presents his boyhood sighting of the famous writer as little more than a curious anecdote. He was 20 years old in 1895, the year of the Wilde Affair. In early April of that year, the newspapers were full of Wilde’s lawsuit against the Marquess of Queensberry. Just a few weeks later, the papers were full of Wilde’s fall from grace. He became a byword for infamy in England and Ireland. Worst of all, his very name became a slur.

Reid lived through it all. The man he had seen promenading through Belfast was now circling a prison yard. How did they make him feel, those broadsheets at the breakfast table? Perhaps they frightened him. An unwelcome premonition of his own future. Desire reduced to commerce, letters sent and regretted, a life spent waiting for the blackmailer’s note or the policeman’s knock. And yet even then Reid must have known that his life, queer fellow though he was, would not take that shape. Wilde’s passions were shallower than Reid’s, and much more dangerous.

The taint associated with Wilde’s name outlived him by decades. Seventeen years after Wilde’s death, C. S. Lewis told Arthur Greeves that he was happy to discuss male beauty, as long as they avoided “everything that tends to sordidness (and beastly police court sort of scandal out of grim real life, like the O. Wilde story).” It was Wilde’s tragedy that his care fully curated persona should come to be synonymous with “grim real life.” Even E. M. Forster kept him at arm’s length. In Maurice, the eponymous character confesses to his doctor that he is “an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort.”

For many, Wilde’s life is a tale of two cities. There is little room for Dublin in this version of his story.

Fifty-four years after Wilde’s death, Brian O’Nolan, a Tyrone man fond of pseudonyms, who wrote novels as Flann O’Brien and a weekly column for the Irish Times as Myles na Gopaleen, railed against a proposed memorial in Dublin: “Oscar Wilde was not an Irishman, except by statistical accident of birthplace. He had become completely déraciné and living in England before he was 20. Not one shred of his literary work even suggests an Irish inflection.” Oscar’s shame could not be allowed to reflect on Ireland.

Wilde’s connection to the North of Ireland is little known. The fact that Wilde was Irish at all is news to some people. Born in Dublin in 1854, Wilde spent his earliest years at 21 Westland Row and 1 Merrion Square. After seven years of boarding school in County Fermanagh, he returned to Dublin for a degree at Trinity College. He did not leave for England until he was 20 years old—still young, but then he would be dead at the age of 46. Nearly half of his short life was lived in Ireland. And yet Oscar’s Irishness can still surprise. In 1998, Jerusha McCormack, then a lecturer at University College Dublin, noted her “frustration at having to explain to Irish students that Oscar Wilde was, yes, indeed, Irish.”

Wilde at his apogee—that brief period between the initial publication of The Picture of Dorian Gray in 1890 and his conviction for gross indecency in 1895—was synonymous with London theatre, London society, and London fashion. His downfall came at the Old Bailey, London’s infamous criminal court, a cramped and airless building notorious for its ability to inspire despair in defendant and judge alike.

After two years of hard labour came Paris: the boulevards, the café terraces, the hotel rooms, and, in 1900, a pauper’s grave at Bagneux. London and Paris: for many, Wilde’s life is a tale of two cities. There is little room for Dublin in this version of his story, despite the recent efforts that have been made to celebrate Oscar in the city of his birth. In Dublin, Wilde is a ghost twice over.

If Wilde’s Dublin days get short shrift in the popular imagination, then there is even less room for Enniskillen. It is true that there is not much to go on. Wilde himself was uncharacteristically tight‑lipped about his seven years at Portora Royal School, situated in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh. The school closed down in 2016, but the building that Wilde knew between 1864 and 1871 is still there. An assemblage of austere, graphite‑colored boxes, Portora perches on a little hill above Lough Erne. Other pupils called Wilde “Grey Crow.” That nickname would do very well for the school itself. It is a bleak and cold place, where high Georgian windows look out over dark water.

The school’s almost theatrically dour character seems better suited to a later pupil, Samuel Beckett, who studied there between 1920 and 1923. Yes, Portora is more Molloy than Earnest. Wilde seems to have taken little from Portora apart from a knowledge of Greek and Latin, but a boy of his gifts would have acquired that knowledge wherever he had gone to school. He certainly learned nothing about Ireland at Portora, which seemed to operate under the pretence that it was sited in Oxfordshire rather than Fermanagh—English history was the only history.

Nor was there much relief outside the classroom. Extracurricular activities suited to a boy like Oscar were thin on the ground. Even the opportunities for sexual experimentation that supposedly abound at boarding schools seem to have passed him by. No wonder that in later life Wilde would revise his time at school down from seven years to one. When he was convicted of gross indecency in 1895, the authorities at Portora revised his time down even further, from seven years to none. His name was removed from the school’s Honours Board. The letters O. W., which he had carved into a windowsill as a boy, were scraped away by the headmaster.

The removal of this childish graffito is particularly affecting. That the masters were aware of it at all in a large school, a building presumably scrimshawed with scratches and doodles made by generations of bored boys, is telling. Those letters on the windowsill were a part of school history for a while. They had been made by a boy who had gone on to do great things. But the boy had gone too far in the end. The school’s history had to be scraped back, given a fresh lick of paint.

Portora was not a glamorous start to Wilde’s life. It was a dun seven years that even he could not be bothered to mythologize. Instead he minimized his schoolboy years, and succeeded in doing so. But there was one part of his Irish childhood that would follow Wilde across the sea to England. A tiny part of his childhood, admittedly. The merest scintilla of his youth. Yet this was a figure from Oscar’s past who would prove instrumental in his downfall, though few now remember Sir Edward Carson for that reason.

He is better known as the man who created Northern Ireland.

The facts of Wilde’s downfall are so well known that a brief summary will suffice. He met Lord Alfred Douglas in 1891. Douglas was beautiful, narcissistic, and bored. Wilde never looked back. By 1893, the pair were inseparable. Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, became increasingly agitated by his son’s association with London’s foremost dandy.

Things came to a head when Queensberry left a card for Wilde at his club in February 1895. The card read: “For Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite [sic].” Posing is the key word. It meant that Queensberry could insult Wilde without being prosecuted for libel—he was not accusing Wilde of being a sodomite, but of posing as one. Being a sodomite was a crime, posing as one was not. Perhaps the misspelling of sodomite was a defense of the same kind—accusing a man of “somdomy” could hardly be considered libelous—though from what is known of Queensberry’s intellectual capacity, it is more likely that he simply could not spell the word.

Later came the questions about the boys. Did Mr Wilde recognize this name? And this name? And this name?

Despite the card’s careful phrasing, Wilde sued Queensberry for libel. This was against the advice of many of his friends. The card was insulting, but it had been a personal insult delivered from one man to another. There was no danger of Queensberry’s accusation reaching wider society unless Oscar chose to publicize it by taking legal action. And the court room was no place for a man like Wilde, even as the injured party. His very private life left him vulnerable to counterattack.

Edward Carson was approached to defend Queensberry. Initially, he demurred. Like Wilde, he had been born in Dublin in 1854. They had played together as children on holidays in County Waterford, and the two men had attended Trinity College at the same time. They had bumped into one another once or twice in London over the years, though they were never friends. Carson felt that this prior association with Wilde, however slight, presented a conflict of interest. He would not defend a man accused of libeling one of his acquaintances, especially a man like Queensberry, an oafish buffoon whose one distinction in life was having been an enthusiastic proponent of cremation.

Carson changed his mind when it became clear that Queensberry’s allegations could be definitively proved in court. Rent boys had been tracked down, witness statements taken, gifts from Oscar to his amours seized as evidence. This change of heart is intriguing. No doubt the reality of Oscar’s many liaisons shocked the deeply religious lawyer into action. Equally, it seems arguable that Carson had initially refused the case because he did not think it possible to win: Wilde’s prose and plays exhibited a decadent sensibility and a queer approach to morality, but this was nowhere near enough to prove that Queensberry was correct to call him a sodomite. Now that the labyrinth of Wilde’s private world had been mapped, the marquess’s acquittal seemed certain.

Edward Carson’s cross‑examination was a sensation. Wilde’s wit, charm, and talent for outrageous (though formulaic) paradox were no match for Carson’s dogged questioning. His very first sally was a victory. Wilde had stated to the court that he was 38. Carson, who knew that Wilde had been born in the same year as himself, reminded the playwright that he must be at least 40 years old. A small moment, but it mattered. Wilde had perjured himself. Later came the questions about the boys. Did Mr Wilde recognize this name? And this name? And this name? And had he given this boy a cigarette case, and that boy a new suit of clothes and a silver‑topped cane? Why had he done that? Why, Mr Wilde? Why, why, why?

Wilde’s wit faltered. The paradoxes were replaced by desperate little quips. Spectators in the courtroom had laughed along with him at first. Now they eyed him coldly. On the third day of the trial, Wilde’s barrister dropped the case against Queensberry. It has been said that Wilde had to seek his fortune in England for the simple reason that the Irish are not impressed by clever talk. In the end, perhaps it was inevitable that a fellow Irishman would be the one to run him to earth.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Stranger’s House: Writing Northern Ireland. ©2023 Alexander Poots and reprinted by permission from Twelve Books/Hachette Book Group.

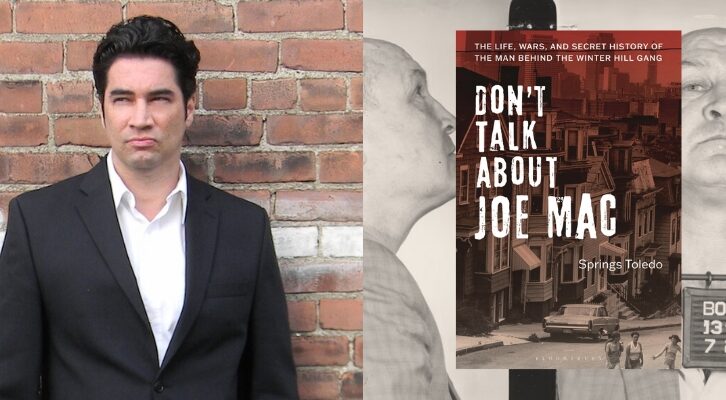

Alexander Poots

Alexander Poots was born in London in 1985. After studying at the University of Manchester and Magdalen College, Oxford, he worked as a bookseller. The Strangers’ House is his first book. He lives in Belfast.