One morning at half-past eight precisely, Colonel Ennio Molinas sat down at his desk at the head of a large room in Cip (Cipher Office). Like all other servicemen attached to the Ministry, he wore civilian clothes. Since he was the head of the department his desk stood on a small platform from which he could supervise the desks of his decoders: a sort of dais. The walls were lined with tall shelves filled with books and records: dictionaries, encyclopedias, atlases, directories, sets of newspapers and periodicals, the basis for all sorts of reference and research. The whole great office had been organized for the war, and functioned at a slacker pace nowadays; but the staff of the department was still complete. The men who worked there were the best in the country at the particular work concerned. They were known jokingly within the Ministry as the “twenty–four geniuses.”

The Colonel smoothed his whiskers, opened the daily register, read the morning’s notes made by the secretary shortly beforehand and looked up to take the roll call. Eight of the twenty-four desks were empty. “Ahem,” he muttered to himself in his own particular way. One of the decoders in the front row caught his worried glance and smiled at him. The Colonel, who was always pleasant yet knew how to keep his distance, shook his head. The young man’s smile broadened: “If things go on like this, sir, the department will be empty in a couple of days.” Molinas nodded silent assent.

At this point Sbrinzel, the absurdly lean and hungry-looking secretary of Department Int (Interception and Troop Movements), came in with the sheaf of messages to be decoded. Despite his modest position Sbrinzel commanded much respect. Some said that he was related to the Minister of Internal Affairs, but this may have been nonsense. Others flatly proclaimed him a spy. In short, he was feared. People spoke guardedly in his presence.

The Colonel, seeing Sbrinzel enter, checked an instinctive movement to stand smartly to attention as though Sbrinzel were a superior. Instead, he smiled broadly.

Sbrinzel went up onto the platform, put down the file and indicated the desks, a third of which were empty, with a wink. “Well, sir, something of a purge, eh?” For some reasons his jokes were always ambiguous.

“Influenza, my dear Sbrinzel . . . this year it really is an epidemic . . . luckily it’s taking quite a harmless form so far, no complications . . . four days in bed and it’s all over . . .”

“Eh, four days! And sometimes four years, eh!” leered Sbrinzel, launching into one of his hateful laughs, dry, harsh and completely lacking in inner gaiety.

Molinas did not understand. “Four years? How could anyone’s influenza last four years?”

“Eh”—Sbrinzel invariably began and ended his speeches with this unpleasantly nasal sound—“I quite agree that the present form is mild, but personally I would prefer the Spanish variety, with all its attendant risks . . . This epidemic is unlikely to dispatch anyone to the next world, but it’s unpleasant all the same, eh!”

“Well, naturally. Influenza is never exactly pleasant!”

“Eh, it’s quite plain that you, sir, know nothing about it, eh.”

“About what? What should I know?”

Sbrinzel shook his head. “For the head of Cip, if you’ll excuse my saying so, sir, this is a bit much. I, for instance, understood without any assistance.”

“Understood what?” asked the Colonel, now faintly disquieted.

“Eh, eh—I could confide in you, I suppose, you’re a responsible man, reserved; you’d hardly occupy this position if you weren’t”—he paused at length to savor the Colonel’s anxiety, then went on mysteriously, in a lower tone—“But, sir, have you not noticed . . . have you not noticed that this influenza does not choose its victims at random, eh?”

“State influenza! Don’t you think it’s wonderful? Influenza which attacks only pessimists, skeptics, opponents, enemies of the country lurking all over the place.”

“I simply don’t understand, my dear Sbrinzel, I really don’t . . .”

“Eh, then I shall have to spell it out word for word. These bacilli, or viruses, or whatever the hell they’re called . . . well, they have a special flair, they pick people out as if they could read into their very hearts . . . and there’s no way of deceiving them, eh!”

Molinas looked at him in perplexity. “Look, my dear Sbrinzel, you may feel like joking . . . but as long as you continue to speak in riddles, how do you expect me to understand? Perhaps I am a little slow today . . . I woke up with a headache . . . I hope I . . .”

“Eh, not you, sir, not you! You couldn’t have influenza! You’re the very personification of discipline, eh!”

“How does discipline come into it?”

“Eh, I must admit that you’re not at your best this morning, sir . . .” He lowered his voice still further: “The fact is this, sir, to put it crudely: if you get influenza, it means you’re against the government!”

“Against the government?”

“Eh, I found it hard to believe too . . . but finally I was convinced. Believe me, not even we have any idea of the brilliance of the Chief who leads us. . . . A magnificent idea for taking the country’s pulse . . . State influenza! Don’t you think it’s wonderful? Influenza which attacks only pessimists, skeptics, opponents, enemies of the country lurking all over the place . . . while the devoted citizens, the patriots, the conscientious workers are untouched!”

Here the Colonel managed to voice his objection: “But my dear Sbrinzel, how could such a thing happen? You mean that all those absent today are against the government?”

“Eh, just think carefully if you don’t believe it, take the cases one by one . . . you’ll see how perfectly it all fits . . . whose desk is that one, for instance?”

“Lieutenant Recordini’s.”

“Eh, would you be prepared to swear to it that Recordini isn’t against the Regime? Think back a little . . . I’m certain he must have given himself away at some time or other, that he has confided in you, eh . . .”

“Oh, Lord, Recordini certainly isn’t a great enthusiast, but surely that doesn’t mean one should accuse him . . .”

“Eh, come now, State influenza never makes a mistake . . . whose is that other empty desk there?”

“That’s Professor Quirico’s desk, he’s the specialist in triple cipher . . . the most brilliant brain in the department.”

“Eh, there you are then! He’s already had a few brushes with authority, if I’m not mistaken . . . wasn’t he nearly dismissed last year?”

“You’re quite right,” agreed the Colonel, somewhat worried, “but . . . but couldn’t some of them be ill with other things? . . . This is a most dangerous system . . . one could so easily be mistaken.”

“Eh, no fear of that sir, the Information Service sees to that . . . look at your register . . . the names of the absentees are marked with a small red cross if it’s influenza . . . perfect, eh?”

The Colonel passed a hand over his forehead. And what if I get ill too? he thought. Unfortunately I’ve cursed the Chief at times, as well. How can one repress one’s thoughts?

“Eh, a headache, didn’t you say? You’re looking rather pale today, sir, eh!” Sbrinzel gave a vicious little laugh.

“No, no, I feel fine now,” said Molinas, controlling himself. “I feel simply fine, thank goodness.”

“Eh, just as well . . . see you later sir, eh?” He went off, cackling to himself.

Was it just a joke? Had Sbrinzel wanted to make fun of him? Or had the government really put into effect so infernal a means of trying consciences? Molinas considered his eight absent juniors. The more he thought about it, the more he had to agree that State influenza—if that was what it really was—had chosen its victims very aptly. For one reason or another, all eight were men of dubious patriotism, all eight very intelligent, and of course intelligence, as far as matters of political faith are concerned, is known to be a negative element. But here he asked himself, “Surely these wretched bacilli could sometimes make mistakes and affect innocent people as well? Possibly myself? Surely everyone must have had a hostile or irreverent thought about the Chief at some time or other? If I fell ill what would they do to me? Dismiss me? Court–martial? I mustn’t give in at any price, even if I do begin to feel ill.”

And he did feel ill. His headache had become worse. A buzzing in his ears. Overwhelming desire for warmth and rest. With an effort he opened the file that Sbrinzel had brought. He studied the messages and divided them up. But they swam before his eyes.

Under cover of pretending to examine a sheet covered with incomprehensible figures, he took his pulse, using his watch to time the beats: ninety–eight. Temperature? Or just fear?

As soon as he reached home he rushed for the thermometer. He kept it in his mouth for over a quarter of an hour. Finally he plucked up enough courage to look at it and was left breathless: 102.

Well dosed with quinine, ears booming, head aching at every move, he went back to the office that afternoon. Strange: Sbrinzel was waiting for him at his desk, and set malicious eyes upon him: “Eh, sir, excuse my saying so, but perhaps you drank a little too much at lunchtime . . . your eyes, they’re terribly bright, eh!”

“A couple of glasses, certainly no more,” said Molinas to parry the blow.

“Eh, by the way, how’s the headache?”

“Gone entirely,” said the Colonel, thoroughly nervous. He put on a show of having a great deal of work to do, scrabbling helplessly amid piles of papers.

Sbrinzel did go away, but came back a little while later. He enjoyed thinking up excuses for frequent visits. He would continue with his series of sibylline questions: Why did the Colonel have that scarf around his neck? Was he cold? Or did he have a cough? Slight laryngitis?

“None of the juniors with influenza (there were sixteen by now) had yet reappeared. Where were they? Telephone calls to their homes for news were greeted by relatives with the answer ‘He’s not here’ without further explanation.”

Molinas continued to defend himself, but he was tired. Sbrinzel’s words echoed inside his head as if it were a bell. There seemed to be a leaden weight at the nape of his neck. Shivering fits. A confined, burning feeling in the chest. Thoroughgoing influenza, in fact. And not being able to mention it to anyone, because that would make it worse. And that wretched spy Sbrinzel, who had obviously guessed that he didn’t feel well and could hardly wait for his final collapse.

No, he mustn’t give in. The following day the Colonel was still at his post, though his temperature was almost 103 and his head felt like molten lead. “How come, sir, you’re so flushed, eh?”

“The cold, perhaps,” answered the Colonel, determined not to weaken.

“Eh, sir, I do believe you’re shivering. Why on earth are you shivering like that?”

“Shivering? Absolute nonsense.”

“Eh, sir, I really would be upset if you didn’t feel well.”

“Nonsense, nonsense, I say . . . just a slight irritation in the throat . . .” A hundred and two point six, a hundred and two point eight. The Colonel would appear at the office at the usual time with the regularity of a robot, divide the work up among his juniors and then sit motionless at his desk, racked by bursts of hollow coughing.

“Eh, sir, it sounds as though you’ve caught bronchitis, eh?”

“No, no, it’s all in the throat . . . I’m perfectly well, I assure you.”

On the fourth day he was almost defeated. “Let’s go out and have a coffee,” suggested Sbrinzel, obviously intending to put him to some sort of test. Outside it was bitterly cold, and the Colonel’s teeth were chattering even in the warm office.

“No thanks; I’ve got a lot to do today.”

“Eh, we won’t be long: a couple of minutes.”

“No thanks, old fellow.”

“Perhaps you’re not feeling too good, eh?”

“No, no, I’m fine.”

“Eh, I’m sorry, sir. It’s just that you do look a little drawn today . . .”

On the fifth day he could hardly stand up. None of the juniors with influenza (there were sixteen by now) had yet reappeared. Where were they? Telephone calls to their homes for news were greeted by relatives with the answer “He’s not here” without further explanation. In prison? In hiding? Deported? Molinas was certain that he had pneumonia but didn’t dare consult a doctor, who would certainly tell him to go to bed and possibly inform the Ministry.

Sixth day. All twenty-four desks were empty: their occupants all had influenza. Sbrinzel sniggered more insinuatingly than ever: “Eh, eh, you can hardly say the Chief is wrong to distrust intellectuals! What remains there of the famous Cip? Delivery men, porters, night watchmen, clerks, the simple souls, they’re the ones who believe whole-heartedly! . . . While the geniuses are all laid low, the geniuses, the government haters! . . . Eh, eh, sir, you’re the only exception, still holding out!” Sbrinzel winked, as if implying “but you’re of the same ilk and you’ll go too!”

Eighth day. His chest like a pile of burning coals and with a temperature of almost 104, the Colonel entered his office at the usual time. He looked like a ghost. At the thought that Sbrinzel would soon be arriving and would have to be parried he felt a dull surge of sweetish nausea rise from deep within him, rise and rise like the water in a hand basin.

But this morning Sbrinzel was not so prompt. Molinas thought, Perhaps he knows I’ve got influenza, perhaps he’s already reported it and I’m already in disgrace, ruined—and that’s why he hasn’t appeared.

Shortly afterward he heard steps approaching across the silent empty room. Not Sbrinzel, but some slave of his, with the folder of messages. “And Sbrinzel?” asked the Colonel.

The man gestured despairingly: “He hasn’t come today. He’s not coming. He’s in bed.”

“With what?”

“He’s got a roaring temperature.”

“Who? Sbrinzel?”

“He’s got influenza too . . . and an absolutely prize case at that.”

“Influenza? Sbrinzel? You must be joking.”

“Why? What’s odd about it? He wasn’t at all well yesterday either . . .”

The Colonel straightened up on his chair. A burst of life and hope came over him. He was safe, safe! He had won! That miserable spy had fallen, not he! Molinas felt better already, no more sickness, no more burning in his chest, no more temperature. The worst was over.

He breathed deeply. For the first time in years he raised his eyes to the windows and saw, beyond the frozen roofs and under the crystal clear sky, the distant mountains gleaming, white with snow. They looked like silver clouds sailing gaily along, slow-moving, above the worries of the earth. He looked at them: for how long had he been oblivious to their existence? He thought, How different they are from us men, God, how pure and beautiful.

__________________________________

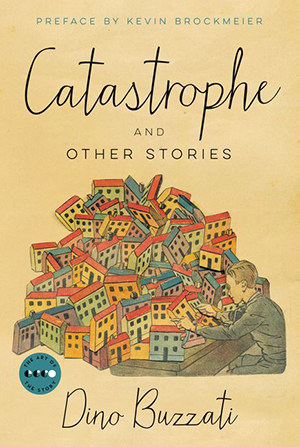

From Catastrophe and Other Stories. Used with permission of Ecco. Copyright © 2018 by Dino Buzzati.