The Enduring Legacy of Eleanor Bumpurs, Murdered by the NYPD For Resisting Eviction

“Gender and femininity have never shielded Black women and girls from unfettered anti-Blackness or police violence.”

I spent summer 2017 mustering the courage to contact Mary Bumpurs. Toward the end of that summer, I stood outside Mary’s apartment, hoping she would not slam the door in my face or give me a tongue-lashing for showing up unannounced. A seventy-something-year-old silver-haired Mary slightly opened the door, holding a large barking dog by the collar. I was frozen.

After several moments of fear, I introduced myself and the reason for my spontaneous visit. Mary graciously listened to me and surprisingly gave me her phone number. Several days later, I was sitting in Mary’s apartment, one she shared with her son, two dogs, and two Cockatiel birds named George and Weezy. That one visit turned into many visits with Mary.

“What is the legacy of your mother’s case?” During many conversations with Mary, I frequently posed that question to her. She always answered the same way, fiercely saying, “To keep her spirit moving. To let people know what happen to her. No more people killed by police.” Mary connected her mother’s legacy to public memorialization and to contemporary activists’ fights for police reform and abolition.

Mary’s hope for public acknowledgment of her mother’s death is not lost on today’s activists and cultural artists. They remember Eleanor and have introduced her tragic story to new generations of social justice advocates. Thirty years after Eleanor’s death, New Yorkers and those beyond the Empire State continue to #SayHerName. Her name and story are mentioned in scholarly conversations, books, newspaper editorials, and in social media posts. Her widely circulated 1980s New York Daily News photograph is featured on political activists’ protest placards and in museum and art exhibitions across the nation.

In February 2017, the Bronx Documentary Center debuted the photography show Whose Streets? Our Streets, an exhibit that featured the photography of more than thirty-eight photojournalists, including that of September 11 victim Bill Biggart. Photographs show 1980s and 1990s New Yorkers taking to the streets, demonstrating against racial injustices and advocating for legal justice for Eleanor Bumpurs and other victims of police brutality. Renowned visual artist and painter Mickalene Thomas features Eleanor Bumpurs in her 2023 Resist series. Thomas is known for her mixed-media paintings and collage installations featuring rhinestones, colorful acrylic, and enamel. Eleanor appears in “Resist #11,” a collage, according to Thomas, inspired by a series of police and racial killings from 2014 to 2022.

Gender and femininity have never shielded Black women and girls from unfettered anti-Blackness or police violence.

Mary’s vision to see an end to police violence has not been realized. Police brutality continues to be a pressing issue for Black women and girls. They are beaten, placed in chokeholds, sexually violated, and gunned down as they socialize, travel, and work on city streets, as they navigate the nation’s carceral institutions, and as they enjoy the comforts of their homes. And those living with mental health illnesses are also vulnerable to police abuse. They are more likely than the general population to be victimized by police.

Despite the NYPD’s and other local law enforcement agencies’ decades-old investments in de-escalation and specialized crisis intervention trainings and their revised use-of-force policies and procedures, individuals living with mental disabilities still face incarceration and militarized police units. They rarely if ever receive assistance from mental health professionals. And some, especially those experiencing mental health crises, continue to die at the hands of police.

Sixty-six-year-old Bronx mental health patient Deborah Danner hoped her disability would not bring her into contact with the NYPD. In a 2012 six-page personal essay, Danner described the mortal dangers Eleanor Bumpurs and others living with mental health issues face when interacting with police. In “Living with Schizophrenia,” the former computer specialist wrote: “We are all aware of the all too frequent news stories about the mentally ill who come up against law enforcement instead of mental health professionals and end up dead. Teaching law enforcement how to deal with the mentally ill in crisis so as to prevent another ‘Gompers’ [Bumpurs] incident. Gompers was killed by police by shotgun because she was perceived as a ‘threat to the safety’ of several grown white men who were also police officers. They used deadly force to subdue her because they were not trained sufficiently in how to engage the mentally ill in crisis.” Danner’s fears of experiencing a mental health crisis and encountering police came true on October 18, 2016. That day, NYPD sergeant Hugh Barry fatally shot Danner in her Bronx home.

Hearing of Danner’s killing, Mary was reminded of her mother’s death. “I have never gotten over the outrage of that day. I relive it every time someone is killed by the police. That’s something that I’ll never get over.” Eleanor Bumpurs’s granddaughter Shantel Bumpurs, who was not yet born when Eleanor was killed, spoke to a reporter about the parallels between Danner and her grandmother’s killings. Articulating the Bumpurs family’s lingering pain and lack of police accountability, she said, “My family went through a lot of the same troubles, but nothing has changed. It’s shocking after all these years there is no justice.”

Unlike the killings of Deborah Danner and Eleanor Bumpurs, many Black women’s police murders are barely visible. Their narratives garner little-to-no media attention or political mobilization, and their stories are seldom foregrounded in contemporary conversations about state violence. Erasure from such conversations suggest that women, particularly Black women, are not victims of police violence and that gender protects them from police brutality. This is hardly the case.

The campaign makes clear that women’s violations should not be an afterthought.

Gender and femininity have never shielded Black women and girls from unfettered anti-Blackness or police violence. In a 2015 statement titled “Modern Day Lynching of Black Women in the U.S. Justice System,” the Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH) rightfully stated that Black women and girls “have never been afforded a femininity that deemed them innocent.”

On the contrary, they “are readily blamed and maligned [brutalized] rather than assisted or protected.” A failure to produce gender-inclusive narratives on policing and recognize “the terror of the mundane and quotidian” has broad implications for victims and survivors. Limited visibility of the varying intersections between race, gender, and policing overlooks the everyday dangers looming over women’s and girls’ lives and disregards their collective struggles against what ABWH describes as a “modern-day Red Record of anti-Black female violence.”

Like their foremothers of the 1980s, Black women scholars, cultural producers, and political activists continue to spearhead anti–police brutality movements. In 2014, one year after organizers Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi created the #BlackLives-Matter movement, legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw’s African American Policy Forum and Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies and surviving families of police brutality launched the #Say-HerName campaign. #SayHerName “mobilizes around the stories of Black women who have lost their lives to police violence.” The campaign makes clear that women’s violations should not be an afterthought.

Documentary filmmakers and other artists have lent their labor to bringing greater visibility to gendered police violence. In 2020 Black filmmaker Yoruba Richens and the New York Times premiered The Killing of Breonna Taylor, a moving film that centers on the no-knock police raid that led to the twenty-six-year-old emergency medical technician’s death.

In October 2020, New York City activist Tamika Mallory and other members of the social justice group Until Freedom organized the State of Emergency Rally. Held near 2020 Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s Manhattan hotel on 62nd Street, the demonstration, while highlighting the importance of voter participation in the presidential election, brought together “the mother of #BreonnaTaylor, the family of #EleanorBumpurs and many others who have lost their loved ones to police violence.” In a rare public appearance, Mary Bumpurs and her children and grandchildren participated in the rally.

We need histories that render visible victims’ full and multifaceted lives.

Standing next to her grandmother Mary, Eleanore Bumpurs, a working-class mother of two and a public housing resident, spoke on behalf of the family. She gave an impassioned speech about her great-grandmother, Eleanor, her namesake and someone she has only known through family stories and newspaper accounts. Eleanore tearfully articulated her frustrations with ongoing police violence, asking the crowd, “When does it stop?” and “Where is the justice?” for her grandmother and for Breonna Taylor and other victims. The budding activist wanted attendees not to forget what happened to her great-grandmother.

Eleanore’s appearance at the State of Emergency Rally is telling. Her testimony reveals intergenerational family pain. “The death of my great-grandmother really messed up my whole family. It’s still a sore soul-touching subject for the family. [My family] still get angry about it.” It also exposed to rally attendees a different kind of trauma. For Eleanore and other Bumpurs grandchildren and great-grandchildren, Eleanor’s death meant mourning the loss of a woman they never got the chance to know. Police violence robbed Eleanor’s progeny of experiencing the often special relationship between grandmothers and grandchildren.

A new generation of family activists like Eleanore Bumpurs, political organizers, and scholars are committed to telling Black women’s heartbreaking stories of police violence. Those complicated and often hidden stories are important to share with society. They spark global outrage and empathy for victims and their families. They inspire international movements for legal justice and police reform and abolition. Collective stories and testimonies about police violence represent powerful resistance strategies against inequitable policing and racist socioeconomic and political regimes. Yet, as this book has shown, we must go beyond narratives primarily centered on human violation and death.

Stories focused on violence reduce individuals to one-dimensional portrayals. They often ignore people’s complex life histories. They advance incomplete narratives and falsehoods, causing victims to lose their identities. Singular stories leave persons frozen in time, limiting their socioeconomic and political possibilities and trapping them in death photographs, video footages, and protest hashtags.

We need histories that render visible victims’ full and multifaceted lives. Restoration of personal identities acknowledges rich and sometimes complicated life experiences: the joys, the connections to family and community, and the personal hardships. An account of state violence victims’ interior worlds encourages the public to invest in their layered and vibrant lives and compels us to analyze their tragic deaths in more meaningful ways.

__________________________________

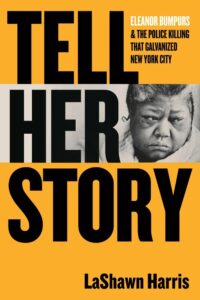

Excerpted from Tell Her Story: Eleanor Bumpurs & the Police Killing That Galvanized New York City by LaShawn Harris. Copyright 2025. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.

LaShawn Harris

LaShawn Harris is an associate professor of history at Michigan State University, the former managing and book review editor for the Journal of African American History (JAAH), and a scholar of African American and Black women’s histories. Her first book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Number Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy, won the Organization of American Historians’ (OAH) Darlene Clark Hine Award for best book in African American women's and gender history and the Philip Taft Labor Prize from the Labor and Working-Class History Association (LAWCHA). Harris’s work has been featured in several outlets, including TV-One, Glamour, Huffington Post, Vice, and the History Channel. Follow her on X @madameclair08.