The island nation of Mauritius lies about 500 kilometers east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. It is best known for having been the home of the dodo, a flightless bird that was mercilessly picked off to extinction by Dutch sailors (and other invasive mammals like rats) who landed there in the late 16th century. Off its coast is the tiny island of Iles Aux Aigrettes. Since being designated a wildlife refuge in 1965, Iles aux Aigrettes has been the site of a sustained experiment carried out by the Mauritius Wildlife Foundation. Under the leadership of its scientific director Carl Jones, the MWF has been working to reestablish, as authentically as possible, the island’s pre-colonial ecology.

The dodo is gone forever, but the endangered pink pigeon, telfair skink, ornate day gecko and several other species have been carefully bred, a scrap of forest has been painstakingly restored, and non-indigenous animals (cats, for example) have been unceremoniously removed. The Mauritius tortoise is also extinct, so the Foundation imported a cousin species from Aldabra in the Seychelle Islands. These gentle giants, some over 200 years old, roam the trails as they will. They seem to think they have all the time in the world.

Though allowing a minimal human presence necessary to bring the island to self-sufficiency, the objective of the MWF’s initiative has been to recover a bit of lost ecology in which humans used to have, and some day will have again, no place. The small group of volunteers who maintain this fragile experiment live lightly on the island; they record behavior and reproduction of the fauna, while also taking care to stay out of their way.

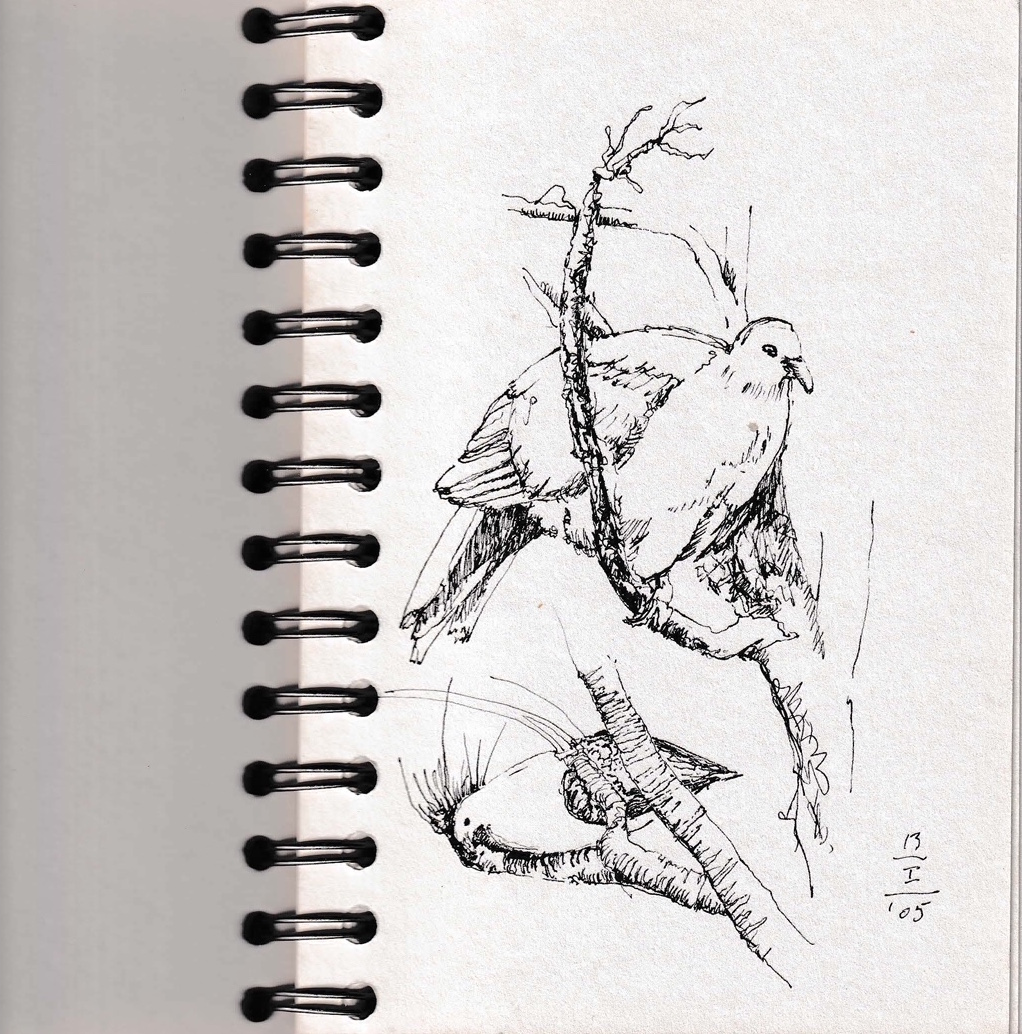

In 2005, my daughter was one of these volunteers, assigned to monitor pink pigeons by sitting motionless with them in the treetops for hours each day. I had the privilege to spend some time there with her and the team, by day tiptoeing behind the giant tortoise Shorty as he lumbered along the paths, and at night watching from my cot the weird shadows of moonlit geckos as they skittered across the walls. While I was there, one of the women ferried a delicate tortoise egg from a hatchery on the mainland, tucked in her bra to keep it warm, then carefully placed it among others on a nest of soft clothing in a dresser drawer. The next day one of the eggs hatched, and I reckoned that this tiny creature might, with some luck and the aid of our humility, outlive our great-great grandchildren on this very island, long after the last human has left.

Sketch of pink pigeon, courtesy of Jill Stoner.

Sketch of pink pigeon, courtesy of Jill Stoner.

The dedicated work of the MWF seemed like tangible progress, and over the past 15 years, I’ve referred to Ile Aux Aigrettes as “the last island,” a hopeful pocket on Earth that might eventually be completely free of human interference. But on July 25, 2020, some thoughtless crew members on the Japanese-owned ship MV Wakashio steered their vessel much too close to shore in search of a stronger phone signal, running aground on a coral reef. Within just a few days, a thousand tons of oil had gushed out into the Indian Ocean. The conservation director at the MWF reported: “We are starting to see dead fish. We are starting to see animals like crabs covered in oil, we are starting to see seabirds covered in oil, including some which could not be rescued.” Already, the viscous black crude had washed up on the beaches of Ile Aux Aigrettes.

What is remarkable is not that Ile Aux Aigrettes is contaminated once again. Rather, it is remarkable that our hapless blunderings through the oceans took this long to reach its shores. The trash accumulating in our largest ocean, referred to as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, is now three times the size of Texas. Manipulated by circular currents called gyres, plastics and other materials both collect into snarly masses and decompose into tiny pieces, endangering sea creatures by catching them up in tangles of nets and by entering their systems when mistaken for food. Like the raw petroleum from which it is made, these products, so ubiquitous in our daily human lives, have now become ubiquitous in the lives of nearly all living things. The billions of bits bob along on the gulf streams from one continent to another, from ocean to ocean at the rate of eight millions tons each year.

Landmasses that go by the name island will no doubt remain evident, scattered amidst our expansive oceans. Powerful currents will continue to swirl around them even as melting icecaps slowly eat away at their edges, and plastic detritus piles up on their shores. But the idea of island, as a world unto and within itself, implies that there still might exist innocent and isolated systems, of the kind that Ile Aux Aigrettes might have been. This is no longer possible.

*

During the first decade of the Cold War, on the island called Bikini in the South Pacific, a series of nuclear weapons tests left an atoll poisoned for the next ten millennia or more. Residents were evacuated from Bikini to other islands in the Marshall archipelago before the first atomic blast, but Pacific breezes blew the airborne radioactive dust downwind, where it settled like snow. Children played in the unfamiliar white substance, centimeters thick on the ground. It seemed to them like magic. And then they died, of cancer.

Their isolated world, until that moment preserved in a semblance of pre-industrial innocence, was unintentionally but tragically destroyed, collateral damage of both pure scientific progress and a power competition among nations, recklessly deployed in the guise of deterring war. These islands in the Pacific were islands no more.

To reach back much further, one might say that the idea of island began its journey toward obsolescence in the same era that struck the dodo dead, when European explorers proved what had been known for centuries—that indeed the world is a sphere. Until then every map had been a patch of some future quilt, a picture indeterminate, its borders terrae incognitae and cartouched with mythic creatures of the sea. Somewhere beyond the paper’s edge was the precarious rim of the earth. Those brave voyages (never mind their disastrous consequences for Indigenous people and flightless birds) were lines of connection, like the Silk Road or Roman aqueducts, bringing resources, language and ideas from one place to another. These were the first threads in a developing global infrastructure, the first challenges to island-as-idea.

Over time, multiple and increasingly complex infrastructures have eroded the age-old myths and meanings we invented for our islands.In western literature and myths, islands have functioned for centuries primarily as ideas. Whether Eden or exile, whether paradise or prison, whether retreat or exclusion, “island” is one of our most versatile and malleable metaphors—we construe its meaning to suit our story. Yet connected as it is to an image of solid matter bounded by fluidity, the idea of island is also absent of ambiguity, and thus curiously innocent. Such simplicity lends itself to allegory. For the sinner, island is exile; for the ascetic, island offers deprivation; for lovers, island provides a paradise. And as allegory, the idea of island loosens the specific geographical implications of land surrounded by water. It can be as large as a continent or as small as a room.

But over time, multiple and increasingly complex infrastructures have eroded the age-old myths and meanings we invented for our islands. These structures traverse our mental landscape against the backdrop of a unified but threatened global ecology. If some oceanic islands like Bikini remained isolated for a few more centuries, their isolation was only by accident. During the past half-century, the idea of island has turned ever darker. Beginning around 1973, its edges could no longer hold.

Nineteen seventy-three was the year of the first Arab Oil Embargo, the year that legislation was first passed to save endangered animals, the year that the Bretton Woods system of monetary management, decoupling the dollar from gold, was abandoned. Thus, a mere decade after Rachel Carson’s seminal study of environmental pollution (Silent Spring, 1962), the picture became clear: resources are finite, and species extinction is the result of many specific and identifiable aspects of human progress. A new kind of war, concurrent with the Cold War, was heating up not between national powers, but in spite of them.

It led to a global consensus that achieved the Paris Climate Accord in 2015. This consensus, a de-politicization of the sort that occasionally emerges in times of crisis, was promising and real, if fragile. In these days of hyper-partisanship, we tend to forget that one of the last documents signed by Republican President Richard Nixon in 1973 was the Endangered Species Act, the purpose of which was “to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost.” (Emphasis mine.)

Also in 1973, the British writer J.G. Ballard wrote the novel Concrete Island, a prescient allegory for its time, and for ours. Anticipating the trappings of globalized structures that were escalating their influence on the cultural landscape, he isolated his protagonist Maitland not by shipwreck on a bit of land surrounded by the sea, but by car-wreck in a concrete wasteland surrounded by motorways. No water laps at the edges of Maitland’s island; but, like Crusoe, he is nevertheless marooned in abject isolation. He scavenges the disused objects of civilization to recreate a semblance of home. Over time, in dubious companionship with a former prostitute and a derelict tinkerer, Maitland finds himself content in his new circumstances and at one with the island.

We can read Ballard’s story in multiple ways; the meaning evolves differently from decade to decade, and depending upon one’s own political context. In July 2016, this British literary work became an allegory for Britain itself, as the nation voted to exit the European Union. Of all the things driving that vote, nostalgia was certainly part of a dream-state that produced the election result: a desire to become an island again.

*

Such an island may be the dream of those who still talk and vote as isolationists. Such an island represents to me and to the overwhelming majority of Americans today a helpless nightmare of a people without freedom, the nightmare of a people lodged in prison, handcuffed, hungry, and fed through the bars from day to day by the contemptuous, unpitying masters of other continents.

–Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Commencement Address, 1940

Article continues after advertisement

In the years following the first major global conflict, then-president Roosevelt saw that a defensive and insular sovereign territory fighting back the creatures at its margins was doomed to fail under its own weight. He reminded us, in this fragile period between two wars, that isolationism is a false power and a slave to Darwinian hierarchies, to contests determining winners and losers in a zero-sum game.

Atmosphere is the most ubiquitous of all earth’s physical networks; according to scientific consensus, its character is now a by-product of human actions.As a more recent US presidency so clearly revealed, the island zeitgeist Roosevelt feared, fought, and pre-empted for almost eighty years has been awakened. Nativism and protectionism continue to rise up around the world, and the architects of such would-be islands are not motivated by nostalgia for a more innocent time. Instead, they are dedicated to ever more sinister zones of isolation. In these current political climates, fake news circles like a malignant wind, sealing off parts of national populations from networks of discourse and debate.

This quest for separation, however, is a futile fantasy, a deluded denial of interdependent networks and climatic realities. Atmosphere is the most ubiquitous of all earth’s physical networks; according to scientific consensus, its character is now a by-product of human actions. We are now, as poet Adam Dickinson has written, “a people of the resin,” living in a world where “resins are always falling from the sky.”

This human-altered atmosphere is as much a part of defining our era as the ground-based strata that give definition to our current epoch, layers like the white dust of radioactivity, or petroleum-based particulates compressed and preserved in landfills. But while geologists may define the Anthropocene only by such layers, atmospheric strata tell an equally compelling story about climate. These include both the physically changing climate caused by our exploitation of the earth’s resources, and the equally dangerous climate of lies that denies human responsibility for those changes.

The English origin of the word climate traces to late 14th-century Scots, where it is defined as “a horizontal zone of the earth.” But looking further back, to Greek (klima) and to Latin (climatis), the meaning is “a sloping surface of the earth,” hence the sister word “to climb.” And these Greek and Latin words each derive from the Proto-Indo-European root klei, a verb meaning “to lean,” implying contingency. Indeed, climate is neither flat nor independent. The pandemic of 2020 brought greater clarity to this truth, as various climates and atmospheres, including our lust for travel to faraway islands, spread the SARS-CoV-2 pathogen worldwide. Not the least of these were microclimates formed of contaminated droplets, issuing from the unmasked faces of the very people who denied the pathogen’s threat.

Though science may cure a particular pandemic, or even ameliorate the severity of our climate crisis, it cannot engineer a clear path out of the wicked dilemmas intrinsic to global interdependence. Instead, our current moment requires a new and shared climate of thought that acknowledges and even embraces the end of the island idea, and its implied state of innocence. Whether as a perceived safe haven from pathogens and petroleum byproducts, or as a political ecosystem in which lies are disguised as truth, the idea of island is obsolete. Our climate, in its broadest sense, is the slope we all must climb together, as literal and phenomenal atmospheres tilt toward uncertain futures.

Once upon a time, the idea of island provided a destination that allowed our literary imaginations to flourish. These days, the island idea represents a failure of imagination at a moment when we need to imagine the world in its absence.