The Earth and the Flesh: On Channeling the Serenity of the Tao to Endure a Tibetan Expedition

Sylvain Tesson Journeys Across the Changtang Plateau

At four in the morning, the alarm went off. The thermometer read −35°C. There was something profoundly rash about getting out of a sleeping bag.

In order not to suffer from the cold in such conditions meant being organized. Every movement had to correspond to a single note: find a glove, lace one’s boots inside the sleeping bag, keep everything prepared, take off a mitten in order to close a strap then quickly slip it on again. The slightest delay allowed the cold to bite into a limb, and it let go only to sink its teeth into another. Cold prowled inside the body. The body did not become inured to it over time. But by making swift, precise gestures, it was possible to reduce the pain. Munier had so often folded up his tent in winters spent in Ellesmere or Kamchatka that he moved quickly and did not seem to suffer from the cold. Léo’s every gesture was meticulous. He was ready before me. His rucksack strapped, his clothes wrapped tightly. Marie and I scrambled to get ready, we keenly felt the pain of waking in a cold room and were eager to set off walking. According to the Tao, “movement overcomes cold.” This was also the premise of the first law of thermodynamics. That morning, in accordance with Chinese philosophy and thermal physics, we joyously threw ourselves into exertion.

We climbed to an altitude of 5,200 meters along broad ridges. Not being acclimatized, we moved slowly. The peak was a small platform of smooth stone cracked by the ice. Day was breaking and, from the summit, a vista unfurled of the Changtang plateau. A plain spanning 1,000 kilometers that shimmered with dust and was shot through by opalescent marshes. The horizon was the morning mist. Within this emptiness was life, concealed.

I imagined long treks from east to west. There are places whose very names conjure dreams, and Changtang did so for me. Sometimes, these magical words become the names of paintings, the titles of poems. Victor Segalen dreamed of Thibet, a place he never reached, one he spelled with an “h.”

He saw it as an abyss in which to cleanse the soul. Later, Thibet became the title of one of his collections, a declaration of love to inaccessible places. He expressed the Germanic notion of fernweh, a homesickness for the far‑distant he would never visit. Spread out at my feet, Changtang offered up its nothingness to future adventures: it was a kingdom to be conquered, a land to be crossed on horseback, in formation, pennants fluttering. One day, we would step directly onto its arid terrain. I was happy to have seen the plain from above. I made an appointment with a place I would never know. We spend two hours at the summit without seeing a single animal, not even a raptor. A bleeding piece of earth marked the place where the Chinese had gouged the land with bulldozers. Prospecting for metals?

That morning, in accordance with Chinese philosophy and thermal physics, we joyously threw ourselves into exertion.

“The whole area was cleared,” says Munier, “like my part of the Vosges. When I was young, back in the 60s, my father warned his fellow citizens. He foresaw disasters. Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring to condemn the use of pesticides. There weren’t many people back then who saw the looming threat. René Dumont, Konrad Lorenz, Robert Hainard: they were wasting their breath. My father fretted, he agonized, people called him a leftist, in the end it made him sick, cancer of despair.”

“He suffered the ills of the earth in his flesh,” I say. “If you like,” says Munier.

*

We spent a day returning to the center of the world, our lake. Night was falling, and, after an eight‑hour trek, we sat on the lake shore. The silence thrummed. The shadowy ranks of the Kunlun Mountains mounted a friendly guard. The vast plain was empty. No sound, no movement, no scent. This was the great sleep. The Tao rested, not a wrinkle stirred the lake. From its stillness, wisdom was born.

The ten thousand things stir about; I only watch for their going back.

Things grow and grow, But each goes back to its root.

Going back to the root is stillness.

I loved this narcotic abstruseness. The Tao, like the whorls from a Havana cigar, tracing pleasing enigmas. We are not called upon to understand much, but drowsiness is as voluptuous as reading Saint Augustine.

Monotheism could never have been born in Tibet. The notion of the one God had been forged in the Fertile Crescent. A throng of crop farmers and livestock farmers converged. Along the riverbanks, small towns appeared. It was no longer enough to simply slaughter a sacrificial bull to the mother goddess. Communal life needed to be ordered, harvests celebrated, sheep led safely home. They forged an image of the world that glorified the herd, the pack. Invented a universal thought. The Tao remained the creed of a solitary soul, wandering the plains. The faith of a lone wolf.

“Read the Tao again!” Léo said to me.

“All things originate from Being.”

No sprinting antelope came to contradict this verse.

__________________________________

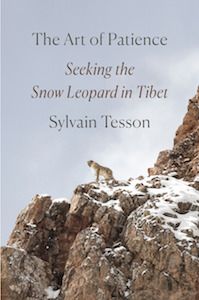

From The Art of Patience: Seeking the Snow Leopard in Tibet by Sylvain Tesson, translated from French by Frank Wynne, to be published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Editions Gallimard, Paris. Translation Copyright © 2021 Frank Wynne.

Sylvain Tesson

Sylvain Tesson has traveled the world by bicycle, train, horse, and motorcycle, and on foot. His bestselling accounts of his travels have won numerous prizes, including the Dolman Best Travel Book Award. Berezina is his first book to appear in English.