The Doors’ John Densmore on the Time Van Morrison Left Him Hanging Onstage

When All Else Fails, Smile and Play the Tambourine

On the night The Doors were fired from our first club gig, Ronnie Harran, the booker for the famous Whisky a Go Go, saw us and offered us the “house band” slot up the street. The London Fog Club had dumped us not because Jim was in a fog that night (which he sometimes was), but because a fight broke out and they blamed the band. Fortunately, Ronnie had good ears and knew we were headed somewhere. She also headed with the handsome lead singer to her boudoir, but that’s another story.

The first set at the Whisky was at 9 pm, when nobody was in the club. The headliner came next, then we did our second set, and finally the headliner closed the night.

We were quite nervous those first few weeks. The result was a horrible review from Pete Johnson of the LA Times. It was so horrible that, as I told the rest of the band, maybe it was good negative PR, since it made us sound like something interesting to see. After getting our feet wet, we jumped in full throttle and tried to blow off the stage each of the famous acts that had the big billing. The Rascals, Paul Butterfield, The Turtles, The Seeds, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, The Animals, The Beau Brummels, Buffalo Springfield, Captain Beefheart—all of them had to deal with us. I mean, of course we loved and admired all of these creative musicians, but we also were a force to be reckoned with ourselves.

We started to develop a following, freaks who loved freeform dancing and would show up for our first set each night. The great owner-promoter Elmer Valentine smartly took down the go-go dancing cages, sensing the new movement of “hippies” forming. It was our turf now. After we finished some of our songs, instead of applause, silence filled the room.

Most people are afraid of silence. We weren’t. The astrophysicist [Neil deGrasse] Tyson says that “dark matter”—the spaces in between the stars and the planets—is as important as matter, and perhaps even more important. Likewise, it’s the space the musician makes in between the notes that gives music the human element. When drum machines were first invented many years ago, they had a “human” button, which, when pressed, sped up or slowed down the machine. I guess human error is a good thing, or at least something that elicits compassion. So something scary, but very attractive to humans, resides in that “dark matter” space where sound gets swallowed up by silence. Complete emptiness. The Void. It was hard for some acts to follow us because of the ominous vibe we left in the air.

We heard that Elmer booked Them, the Irish band whose lead singer, Van Morrison, had penned “Gloria” and “Mystic Eyes” and so compellingly adapted “Baby, Please Don’t Go” to suit his voice and band. We were in awe. As the date approached, the decision to take our cover version of “Gloria” out of our set seemed wise. We thought our take of the song was pretty good, but it was not cool to step on the originator’s toes.

Back then, I hadn’t figured out the importance of both silence and sound in music.On opening night for the “boys from Belfast,” The Doors started with a nervous first set. During intermission, I situated myself at my usual spot on the stairway to the upper balcony. My first book, Riders on the Storm, sets the tone:

Them brashly took the stage. They slammed through several songs one right after another, making them indistinguishable. Van seemed drunk and very uptight, crashing the mike stand down on the stage. But when he dropped his lower jaw and tongue and let out one of those yells of rage, something Irish in me made my skin crawl with goose bumps. Ancient angst.

I was confused about this singer having so much talent while being so self-conscious. Ronnie drove me, Van, and a few other people to a small party at her apartment at 2 am. Most of us made small talk, while Van glowered in the corner. Then all of a sudden he grabbed Ronnie’s guitar and blasted into vocals, singing about being a stranger in this world and wanting to be reincarnated into another time with another face. Ultimately, these lyrics would end up on the transcendental Astral Weeks album. Riders tells what happened next:

It was as if Van couldn’t communicate on a small-talk party level, so he just burst into his songs. We were mesmerized. It didn’t seem appropriate to shower him with compliments, because his music came from such a deep place. So when he finished there was silence for a minute or so. A sacred silence.

I had been somewhat aware of the quiet in between the sounds way back in the sixties. Back then, I hadn’t figured out the importance of both silence and sound in music. I had only an intuitive understanding of it. Once we started getting to know the Irish lads during that magical week, The Doors put “Gloria” back into our set list. The very last night before Van and his crew went back to the Old Sod we all played “Gloria” together. Two drummers, two keyboards, two of everything. Even two Morrisons. After about twenty minutes, we all put “Gloria” to bed after a glorious night.

Van went on to pen many, many important songs. “Brown Eyed Girl, “Crazy Love,” and “Moondance,” to name just a few. With “Into the Mystic,” he seemed to be pointed in a more spiritual direction, which culminated with the hypnotic Astral Weeks. Using jazz musicians and not rehearsing beforehand, Astral Weeks is an impressionistic stream of consciousness. It remains a cult favorite to this day, despite the fact that it failed to achieve significant mainstream sales success for decades. After thirty-three years, it finally achieved gold in 2001. I’ve always said that Astral Weeks is one of my all-time favorite albums, and that sentiment seems widely shared, considering how many lists of “Greatest Albums of All Time” include it.

On November 6, 2008, I got a phone call from “Van’s people,” inquiring whether I wanted to play “Gloria” with him and his band at the Hollywood Bowl. “The Man” would perform some of his oldies up to intermission, then the brilliant album Astral Weeks in the second half. Hell yes! After all, I’d already played “Gloria” with him, his band, and my band at the Whisky in 1966.

I went to the afternoon rehearsal for “Gloria” at the Bowl. There were about fifteen musicians onstage, which is an unusually large group. I guessed that, for the second half, Van needed extra players, strings and the like, to replicate the sound of Astral Weeks. Bobby Ruggiero waved his hand for me to sit down on his drum stool. I did so, then looked out at the thousands of empty seats. Having played this venue twice, I was comfortable sitting on the drum riser and excited about the night that lay ahead. I tested out each drum. It felt easy, which was a relief. With drum sets, the angles are all different for each player, and playing on your own kit feels like wearing a comfortable glove.

Van was nowhere in sight, but they wanted to rehearse. We jumped into the song, and the backup singers sang Van’s lead parts. It was a groove kicking this big band on a tune I knew very well. I threw in my own signature licks, and the musicians turned around, acknowledging me with big smiles.

Then they stopped and said, “We might do a Bo Diddley section in the middle.”

“Okay,” I responded. “I should know that ahead of time.”

“Well, it’s up to Van.”

“Okay. Where is he?”

“In the dressing room.”

“Okay. Why don’t we ask him?”

I could feel a very pregnant pause, and then tension mounting among the players. No one was getting up to go ask Van about the arrangement. It was awkward, because if I didn’t know how they were going to play that section, I could fuck it up and that would be embarrassing for all concerned. I had heard horror stories about Van, like the time he screamed at one of his roadies for bringing him the wrong vintage of wine, but I had a long history with the guy, so I wasn’t going to let that deter me.

“Okay, fine! I’ll ask him!” I said getting up from the drum stool. The musicians looked at me with amazement as I headed toward the dressing rooms. They seemed to actually be afraid of their lead vocalist.

I put my ear up to one of the dressing room doors and could hear Van on the phone. I rapped. He didn’t respond. I rapped harder. Nothing. Then I banged hard, and he finally responded. “Yeah, what?”

“Van, it’s John Densmore. Are you going to do the Bo Diddley section in the middle of ‘Gloria?’”

“Whatever you want” was his response, as he went back to his conversation.

We finished rehearsing, and I went home. When I came back in the evening with my girlfriend Ildiko, we went backstage, since Van had already started. His manager told me the plan was for “Gloria” to be the encore just before intermission. I would walk out with Van, he would introduce me, and then we’d play the song. Easy enough.

We walked out together on that magnificent stage under the shell at the Hollywood Bowl, but I could tell that Van couldn’t take in the applause he was getting. Something was torturing him. Then he began to torture me, though not on purpose, I think.Ildiko and I listened to several songs from the side of the stage. They sounded good, although up close, it was clear that Van wasn’t relaxed. Something inside him seemed to be always on pins and needles.

They finished the last song, and Van the Man exited stage right. Later, Ildiko would say that she could feel Van’s nervous energy. I stood beside him as we waited for our cue. He asked about Ray and Robby, which was sweet. I was reminded of that time a few months after he finished the Whisky gig years ago when I saw him in town and he asked, “How’s Jim doing?” Two Morrisons caring about each other.

We walked out together on that magnificent stage under the shell at the Hollywood Bowl, but I could tell that Van couldn’t take in the applause he was getting. Something was torturing him. Then he began to torture me, though not on purpose, I think. In his preoccupied state of mind, he forgot to introduce me. The band was waiting for their cue to start the song, and it didn’t come. The awkward silence needed to be broken, so the guitar player started the opening chords to “Gloria.” After a few bars, the rest of the band had to kick in, so they did.

Leaving me standing there in front of ten thousand people, wondering what to do. Walking off would have been weird. I spotted a tambourine under the backup singers’ riser, so I walked over, picked it up, and started playing it as if that had been part of the plan. Needless to say, I was not happy. At that moment, I didn’t give a shit about how talented Van was. This was humiliating.

No one in the audience knew that anything was wrong, but yours truly felt tremendously awkward as I worked my way over to Bobby, the drummer. We were trying to figure out how to switch—him jumping up and grabbing the tambourine, me grabbing his sticks and sitting down without missing a beat. It couldn’t be done. If we tried it, the beat would definitely drop for a few bars, and Van the Man would have definitely been pulled out of his “flow.” He would have turned around with a big frown on his face, even though he himself had caused the problem. So I just continued to play the tambourine with a fake smile.

At the finish, we all headed for the wings, with the roaring crowd fading as we exited. Van seemed to disappear. His manager came up to me expounding major apologies. No one would dare try to go look for “The Man” to get his take, let alone an apology.

Ildiko gave me a big hug when I met her at our box seats for the second half. Only she and the Doors’ manager, Jeff Jampol, knew what I had been through. After a few songs from one of my favorite albums of all time, Astral Weeks, we left. The performance wasn’t bad, but the vibe, which only Jeff, me, and our two girlfriends knew about, had taken the wind out of our Van Morrison sails.

Since then, I’ve reduced the capital letter “M” to lowercase “m” when I write about him: Van the man. Also, this book is subtitled Meetings with Remarkable Musicians, not Meetings with Remarkable Men, for a reason. Van blew it. I was going to pay him a compliment in front of ten thousand people, but he didn’t remember to introduce me, so he didn’t get that compliment. I was going to say, “It’s a great honor to be playing with a Morrison again.”

It took me a year or so to get over what had happened because, when someone you know behaves badly, it can cloud your appreciation of their work. Anytime one of Van’s songs came on the radio, I had to change the station. Later, admiration for his gifts crept back into my psyche. “Into the Mystic” won me over again. I just can’t resist the spiritually brilliant music The Man has produced.

When Van Morrison sings, “We were born before the wind, / Also younger than the sun,” he is talking about “the flow.” Even with all his phobias, he usually taps into the jet stream of sound circling the planet. Van has described that feeling in interviews: “It’s just plugging in and going with the flow and then sourcing that energy.”

Jay-Z speaks of getting into “the flow” while rapping. It’s the rapper’s choice whether to go fast with an amazing cadence, like Eminem, or wonderfully slow, like Snoop Dogg. It’s how the rap sits on top of the beats, just as it’s a drummer’s choice whether to push the feel or to lay back. Singers make choices through their phrasing, deciding when to start a line and how long to drag it out.

Van, who obviously listened to early R&B, is impeccable when he’s into his flow. Randy Lewis, the esteemed music critic for the LA Times, hit the nail on the head: “Van Morrison strives to reach a special space through music, an ethereal place perhaps best summarized in the title of his 1970 song ‘Into the Mystic.’ ‘Just like way back in the days of old, [and] magnificently we will float into the mystic.’”

__________________________________

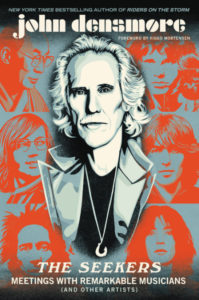

Excerpted from The Seekers: Meetings With Remarkable Musicians (and Other Artists) copyright © 2020 by John Densmore, reprinted with permission of Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.