From close up the warts on the toads look just like capers. I hate the taste of capers, those little green buds. And if you pop one between your thumb and index finger, some sourish stuff comes out, just like from a toad’s poison gland. I poke at a toad’s fleshy rump with a stick. There’s a black stripe running down its back. It doesn’t move. I push harder and watch the rough skin fold around the stick; for a moment its smooth belly touches the tarmac that has been warmed by the first rays of spring sun, where they love to squat.

“I only want to help you,” I whisper.

I put down the lantern they gave us at the Reformed church next to me on the road. It is white with sticking-out folds in the middle. “God’s word is a lamp to your feet and a light to your path,” Reverend Renkema had said as he handed them out to the children. It’s not yet eight o’clock and my candle has already shrunk to half its size. I hope God’s word isn’t going to start fading too.

In the light of my lantern I see that the toad’s front feet aren’t webbed. Maybe a heron bit them off or he was born like that. Maybe it’s like Dad’s gammy leg that he drags around after him across the farmyard like one of those tube sandbags from the silage heap.

“There’s squash and a Milky Way for everyone,” I hear a church volunteer say behind me. The thought of having to eat a Milky Way in a place where there are no toilets makes my stomach heave. You never know whether someone’s sneezed onto the squash or spat in it or whether they’ve checked the sell-by dates of the Milky Ways. The chocolate layer around the malt nougat might have turned white, the same thing that happens to your face when food makes you sick. After that death will follow swiftly, I’m sure of that. I try to forget about the Milky Ways.

“If you don’t hurry up, you won’t just have a stripe along your back but tire tracks,” I whisper to the toad. My knees are starting to hurt from the squatting. Still no movement from the toad. One of the other toads tries to catch a lift on his back, trying to hang on with its front legs under its armpits, but it keeps sliding off. They’re probably scared of water like me. I stand up again, pick up my lantern and quickly shove the two toads into my coat pocket when no one’s looking, then I search the group for the two people wearing fluorescent vests.

She turned the corners of her mouth downwards. They’d been constantly turned downwards recently, as though there were fruit-shaped weights hanging on them.

Mum had insisted we put them on. “Otherwise you’ll be as flat as the run-over toads yourselves. Nobody wants that. These will turn you into lanterns.”

Obbe had smelled the fabric. “No way I’m going to put that on. We’ll look like total idiots in these dirty, stinking sweatbags. No one else will be wearing safety vests.”

Mum sighed. “I always get it wrong, don’t I?” And she turned the corners of her mouth downwards. They’d been constantly turned downwards recently, as though there were fruit-shaped weights hanging on them, like on the tablecloth that goes with the garden set.

“You’re doing fine, Mum. Of course we’ll wear them,” I said, gesturing to Obbe. The vests are only used when the kids in the last year of primary take their cycling proficiency test, which Mum oversees. She sits on a fishing chair at the only crossroads in the village, and puts on her concerned face, lips pursed—a poppy that just won’t open. It’s her job to check that everyone sticks out their arm to indicate and gets through the traffic safely. The first time I felt ashamed of my mum was on that crossroads.

A fluorescent vest comes towards me. Hanna is carrying a black bucket of toads in her right hand, and her vest is half open, its panels flapping in the wind. The sight of it makes me feel anxious. “You have to close your vest.” Hanna raises her eyebrows, staples in the canvas of her face. She manages to keep looking at me like this—with slight irritation—for a long time. Now the sun is becoming hotter during the day, she’s getting more freckles around her nose. An image flashes into my mind: a flattened Hanna with the freckles splattered around her over the tarmac, the way some run-over toads end up in pieces. And then we’d have to scrape her off the road with a spade.

“But I’m so hot,” Hanna says.

At that moment, Obbe joins us. His blond hair is long and hangs in greasy strings in front of his face. He repeatedly smooths it behind his ear before it slowly tumbles back again.

“Look. This one looks like Reverend Renkema. See that fat head and those bulging eyes? And Renkema doesn’t have a neck either.” A brown toad is sitting on the palm of his hand. We laugh but not too loudly: you mustn’t mock the pastor, just like you mustn’t mock God; they’re best friends and you have to watch out with best friends. I don’t have a best friend yet but there are lots of girls at the new school who might become one. Obbe started secondary ages ago, and Hanna is two years below me at primary school. She’s got as many friends as God had disciples.

Suddenly Obbe holds his lantern above the toad’s head. I see its skin glow pale yellow. It squeezes its eyes shut. Obbe begins to grin.

“They like heat,” he says, “That’s why they bury their ugly heads in the mud in the winter.” He moves the lantern closer and closer. When you fry capers they go black and crispy. I want to knock Obbe’s hand away, but then the lady with the squash and the Milky Ways comes over to us. He quickly puts the toad in his bucket. The squash lady is wearing a T-shirt that says LOOK OUT! TOADS CROSSING. She must have seen Hanna’s shocked expression because she asks us if everything’s all right, if all the crushed bodies aren’t upsetting us. I lovingly wrap my arm around my little sister who has put on a sulky pout. I’m aware there’s a risk she could suddenly burst into tears, like this morning when Obbe flattened a grasshopper against the stable wall with his clog. I think it was mainly the sound that scared her, but she stuck to her guns: to her it was that little life, the wings folded in front of the grasshopper’s head like mini fly-screens. She saw life; Obbe and I saw death.

The squash lady smiles crookedly, and fetches a Milky Way for each of us from her coat pocket. I accept it out of politeness and, when she’s not looking, take it out of its wrapper and drop it into the bucket of toads: toads never get tummy ache or stomach cramps.

“The three kings are OK,” I say.

Since the day Matthies didn’t come home, I’ve been calling us the three kings because one day we’ll find our brother, even though we’ll have to travel a long way and go bearing gifts.

I wave my lantern at a bird to drive it away. The candle wobbles dangerously, and a drop of candle-grease falls on my welly. The startled bird flies up into a tree.

__________________________________

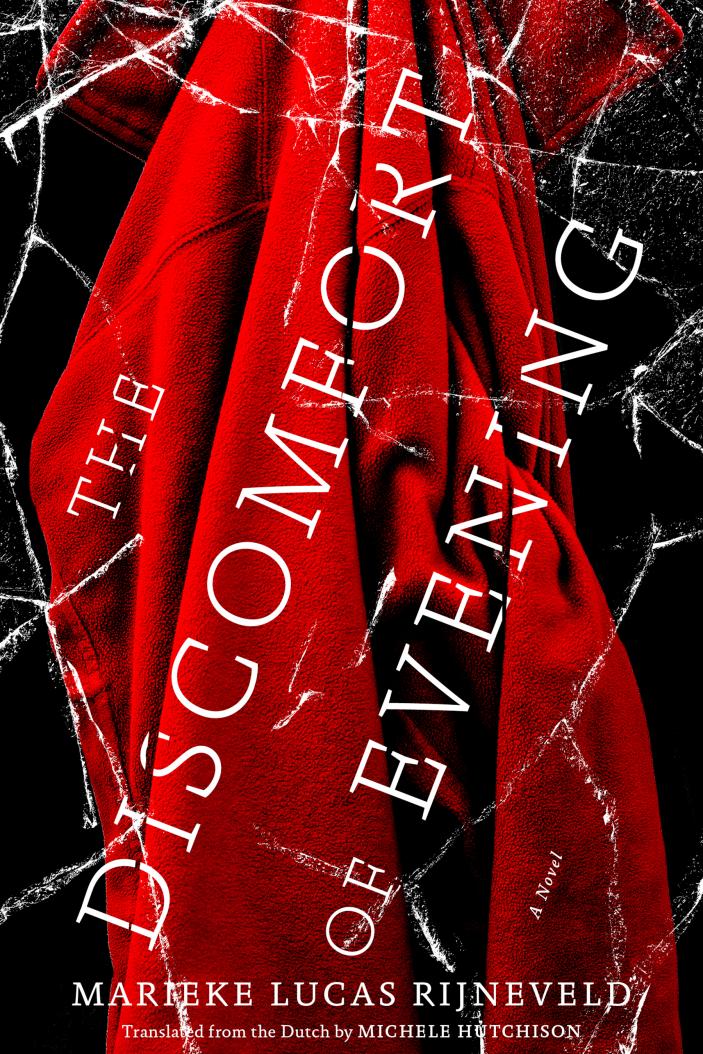

Excerpt from The Discomfort of Evening. Copyright © 2020 by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld. English translation copyright © 2020 by Michele Hutchison. Reproduced with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota.