The Difficulty of Writing About Male Intimacy

Michael Pedersen on Male Friendship and Vulnerability

I always felt an irregular fit for the algebra of male friendship that I was taught to adhere to, a roll call for which I consistently fell short during my boyhood years: too sloppy; too sentimental; too silly; too desperate for their love; too easily a greeter face; too long a bed wetter; trying too hard to work it out.

I recently lost the most valuable friendship I’ve ever had, my dear one left this world dramatically, defiantly, devastatingly. Just weeks later, I took myself to a tower in Northern Ireland—The Curfew Tower at Cushendall—and reflected on the memory of it. I think we lose a bit of ourselves when someone so vital leaves this spinning planet. A little more goes when they were young and tragedy was close at hand. Within the bricks of Curfew Tower, I hoped to claw some back.

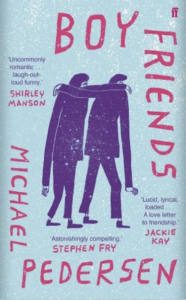

This residency became a month-long scavenge into my own life via the friendships that inhabited me—those that buoyed me up, the ones that broke my heart, the cherished few that sculpted me into the love hungry being I am today. It was an epoch of paying homage to the friends I’ve held closest in my life. Although wildly disparate in their timelines, timbre, and tenacity, each friend I visited in my work, which became the book Boy Friends, arrived rich in sagacity and left me hugely edified. I was fully in love with each of them. We embraced, we hugged and kissed, we championed each other’s quiddity.

Though most are lost to me now—geographically, socially or temporally—I carry them with me always. I am able to love so fiercely because of them. I laud the effect these humans had on me, celebrate my jam-jelly-in-the-centre-of-a-doughnut-turned-heart for knowing them. One thing they all had in common, to my naïve surprise, was that each friend I visited was male—boy on boy to man on man.

I would frequently give too much, too fast, in the male friendships of my boyhood; would give myself over to the friendships in a way that was labelled effeminate or girlish.I grew up with one sibling, a sister, and had a closer relationship to my mum than anyone else in my gargantuan extended family, with nearly thirty first cousins within my ken. I thus grew up bearing witness to, and envious of, the fabulous female friendships that fomented around them both. They exhibited a tender nature and a ritualistic lovingness. I yenned for the physical vocabulary of my sister’s friendships—a corporeal closeness not present nor welcomed in the more stoic male friendships that I seemed to be forging. No linking arms, no cuddling each other when upset, no sharing-the-bed sleepovers, no hand-holding, for fear of rebuke.

I would frequently give too much, too fast, in the male friendships of my boyhood; would give myself over to the friendships in a way that was labelled effeminate or girlish. This would result in everything from playful mockery to ostracization or homophobic slurs. In later years, I served as a trusted confidant for many of these same boys when they had news, sensitive or shocking, they needed to unpack by clandestine means.

For many males of this emotionally restrained persuasion, they will become part of the loneliness epidemic, held back by their own shame or inhibitions from truly expressing themselves—unable to invite other male friends out for a walk, or to dinner, or to confab with them on matters vital to their heart and well-being. This lack of intelligent physical intimacy inhibits many of these men from being more considerate, confidant lovers, their carnality as human beings having been stymied.

At best, this mode of feeling comes hand-in-hand with unfulfilled emotion potential. At worst, it is a killer.

In my book, I delve into this unusual middle terrain whereby men let spill their concerns and trepidations under the caveat of sport or the indorsed occasion of drinking together. Both parlours grant these men the emotional permission (perhaps the emotional passport?) to unfurl their vulnerabilities under the guise and protection of a more stable narrative—the watching of sport, the sense of occasion.

Foremost to this (or rather to me) is the well-cast trope of having “gone fishing”: males setting off with other males to steep in the silence until the guards are down, the pressure ebbs, and it becomes less uncomfortable to simply address the matter unspoken than not to. Often friends are sent off on friendship dates of this ilk and told not to come back until they’ve confessed to all their sins (or, more often, their worries).

Also, such fishing trips, sports away days, and boozy splurges come equipped with the knowledge that’s what spoken about in these sanctioned spaces should be held privy to time and location; it is not be repeated or regurgitated within the general fold of things under fear of breaking the code. These are short-term answers to long-term issues, but progress nonetheless. That these honesties and sensitivities might become more pervasive in each reluctant voyagers day-to-day life is my hope—a chimera worth fighting and dancing for.

In my own writing, I find nourishment in sharing my heart’s desires alongside the sonorous and solemn bits. It was always the way for me, always the path to happiness. Yet it comes with the risk of giving too much of myself and others I love away. Over the years, I’ve learned better what is valuable to the narrative and what might offer the reader the best chance to project their own life into my story. I’ve no interest in writing something that doesn’t proffer the reader in, that doesn’t suggest companionship, and that isn’t as much an invitation to feel as it is a visitation into my life. When the writing gets too personal I look for safe landing paths, a point of universal truth—an objective question within my subjective tale.

My body too is a guide. Sometimes it speaks to me in mellifluent poetics, wispy and verbose, and other times it talks curtly in New York mobster slang. It calls me a motherfucker. It’s my mind’s way of cushioning the steps ahead. My skeleton and organs are as vocal as the people in my books.

It’s no surprise that the contemporary writers and artists best exploring masculinity are those who felt excluded from it during their boyhood or teenage years: those who were labelled unmasculine, fell short of the bar—the emotionally vivacious, vulnerable, flamboyant. Now able to better articulate the forms of masculinity they were (the whole time) inhabiting, they are reclaiming it. From writers like Ocean Vuong, Bryan Washinton and Andrew McMillan, I’ve learned so much in this area. If I become just a small part of this wave of wonderment, a ripple within a ripple, that’s enough, more than enough.

__________________________________

Boy Friends by Michael Pedersen is available via Faber & Faber.