Getting in had been accomplished with extraordinary consistency—no loss of control—and in his delight, he passed up a glance at his depth gauge. The pill had made his mouth pasty and numbed the underside of his tongue. To double-check action of the drug, he slammed the big key on a showcase full of necklaces. This time, the impact produced a clear, shapely tinkling sound: no ebbing or wobbling. Sometimes noises would go into an endless quaver like a cassette tape run too slow. That was usually a bad sign. He slammed the showcase again, savoring the crisp clink attesting to the solidity of the world around him. He crossed the boutique without glancing at the jewelry on display. What he’d come for was always deep in a safe in back, far from prying customers. Another fundamental rule, not to be argued with. No matter the shop, the safe was always the same: fat, black, oafish, and anachronistic, with a huge dial in the middle of the door. A forbidding cube that never rang hollow, that no crane could have lifted or budged so much as an inch. The perfect safe . . . Once in back, he reached a door with a brass plate that said PRIVATE. The big key let him in. Behind it was a sitting room with heavy red draperies, cluttered with bronzes and sculptures. The safe was at the very back of the room, its big black door guarding the entrance to a forbidden citadel. David took his stethoscope from the briefcase and began sounding out the door. The dial rattled, amplified by his instrument. David focused on the clicks rising from the cast iron. Now, more than ever, he needed a musician’s ear. Abruptly incongruous images formed in his mind, and he saw himself in a doctor’s office, leaning over the abdomen of an obese patient. As if following suit, the safe let out a burp, painfully vibrating the stethoscope’s diaphragm. Enough! David thought, as if that naïve magic word were all it took to restore order. Now a great big heart was beating behind the reinforced door, making a dreadful, unbearable racket, masking the clicking of the dial. Then the safe began saying, “33 . . . 33 . . . 33 . . .” with the regularity of a clock bent on running forever. David tore the stethoscope from his ears and swallowed another consistency pill. He was perspiring freely now; sweat trickled in an unbroken stream from his armpits. Without thinking, he patted his jacket pocket, where he kept a dime bag of realism powder. He could sniff it on the glass-topped desk right here and now, but even though the powder curbed oneiric drift, it also hastened the ascent: a side effect he had to keep in mind. He fingered the bag, hesitating. Too much realism and he could take off right in the middle of the heist. He didn’t relish the prospect. Better to try to push forward through the parasitic drift, keeping his eye on the prize. He turned back to the safe and began listening again. At first all he heard through the chestpiece was intestinal gurgling, and he had to strain his ears to make out the faint clicking of the dial as it turned. Click . . . click . . . clack! said the lock. Screw you! the chorus of tumblers retorted. Take your hardware and scram! added the armor plating. They were chanting in rhythm, spinning off endless variations on their simple theme, the singsong harmoniously dovetailing like an operetta with a strangely metallic aftertaste. Each click of the dial was another note the iron choir fell in tune with. David shrank back, his face slick. He mopped his forehead and palms with the starchy handkerchief. A scratching sound from the desk made him turn around. With some anxiety, he saw the jeweler’s severed hand had escaped from the briefcase and crawled across the blotter adorning the desktop. It had grabbed a pen and was now writing in large, tremulous letters, My dear man, you’ll get nowhere tonight. Beat it before the police surround the building. The eyeball was floating in the air, peering at the statues and bronzes; sometimes it swooped down and froze over the ledgers, hovering like a helicopter. David pressed his forehead against the safe’s icy door. He couldn’t back out; it was an easy job. Nadia had said so. Besides, there was no way he could go back up empty-handed; these last few weeks he’d already dived three times without bringing anything back. If this unlucky streak dragged on, they’d soon be accusing him of incompetence. They’d even go so far as to claim his powers were wearing out. I’m rising, he thought as panic seeped in. Yes, we’re going up, the severed hand feverishly scribbled on the blotter. 5th floor: women’s lingerie, silken trifles; 6th floor, children’s department—frantically, David grabbed the dial. The door to the safe let out a loud sigh. Why Doctor, what icy hands you have! the lock snickered. I’m too light, thought David, I’m flying upwards. It’s like my feet aren’t even on the ground anymore. My pockets are full of bubbles. Echoing this last thought, a heavy cut-glass inkwell rose from the desk, wafting gently over the books and the clock. As a phenomenon, weightlessness meant the world of the job was in the process of losing its initial density. Objects hollowed, grew friable, fragile as papier-mâché. A thick leatherbound tome took flight next, joining the inkwell. David touched the door. The metal had changed textures too; now it felt like something between terra cotta and stucco. Might as well. David steeled himself. What are you waiting for? He made a fist, drew it back, and punched the safe with all his might, as if trying to flatten a giant in an unfair match. There was an eggshell crack as his fist hit the steel door. Off-balance, he fell into the cube, his arm shoulder-deep inside the safe. His fingers blindly groped the shelves, fumbled crunching bagfuls of loose stones. He came across bags like that in every heist; the psychologist said it was negative thinking. Objects with a precise shape, however convoluted, would’ve been worth more. The bags invariably meant a small take. He grabbed them anyway.

His heart was beating way too fast. The veins in his left arm were beginning to ache, a painful blister throbbing on his wrist, right over his pulse. He leaned on the desk to catch his breath. He had to stay cool in the face of a nightmare, or else the dream would eject him without regard for decompression stops. He mastered his breathing. If he gave in to the nightmare, the excess of anxiety would result in a brutal awakening as his consciousness tried to flee unbearable images by snapping back to reality. If he wasn’t careful, he’d take off right from where he was standing, literally sucked up toward the surface. He’d rise straight into the air, clothes and shoes tearing away, punch through the ceiling and the whole building like an arrow through a lump of clay . . . he’d lived through it once or twice before, and it was a horrible memory. The feeling of suddenly becoming a human cannonball, tearing headfirst at the most terrifying obstacles: walls, floorboards, ceilings, rafters, roofs . . . Each time he was sure his skull would burst open at the next impact, and even though that never happened, hurtling through buildings of slime was still a disgusting experience. When the dream stopped short, the structure of things weakened, the hardest materials took on an ectoplasmic consistency like raw egg whites or jellyfish. He’d had to make his way through that cloacal mire, arms over his head to streamline his ascent, mouth clamped shut to keep from gulping down the gelatinous substance of a decomposing dream . . .

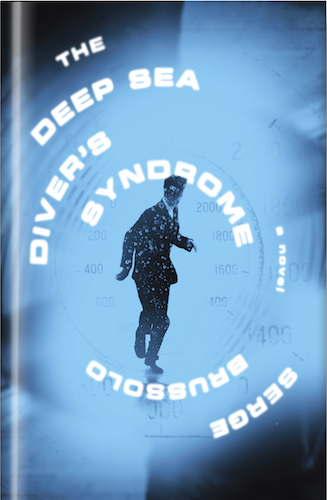

From THE DEEP SEA DIVER’S SYNDROME by Serge Brussolo, translated by Edward Gauvin. Used with permission from Melville House Books. Copyright © 1992 by Éditions DENOËL.Translation copyright © 2016 by Edward Gauvin.