The Death That Galvanized Malcolm X Against Police Brutality

Peniel Joseph on the Case of Ronald Stokes in 1960s LA

On April 27th, 1962, Los Angeles police fatally shot Nation of Islam member Ronald Stokes. Officers mistook him and a group of Muslims removing clothes from a car outside a Los Angeles mosque for criminals. The conflict quickly escalated to a police raid inside the mosque, leaving a total of seven Muslims shot, one killed, and one paralyzed from a bullet wound to the back.

Stokes’s death compelled Malcolm to engage in new dimensions of the black freedom struggle. He discovered a new center of political gravity by returning to the arena that had launched him: America’s racially scarred criminal justice system. Decades before protests against mass incarceration galvanized the black freedom struggle, Malcolm indicted the entire justice system as racist.

His crusade against police brutality and violence against black folk in urban cities paralleled King’s mobilization of southern blacks in Montgomery and Albany. Malcolm transformed Stokes’s death into a political indictment against American democracy, linking systemic police violence in black Los Angeles to structural inequalities that, he argued, gripped every facet of American society.

The melee in Los Angeles shook Malcolm, who had founded the temple five years earlier and knew Stokes personally. The violence demonstrated the tension between the Nation of Islam and law enforcement, something Malcolm would stress in his public account of the events. The black presence in Los Angeles, like in other major cities, had grown exponentially following the Second World War as southern migrants sought relief from Jim Crow and found new economic opportunities.

By the early 1960s, African Americans in Los Angeles and other major cities were experiencing discrimination in housing, public schools, and employment that upended the narratives that claimed Jim Crow as a peculiar problem of the South.

Northern-style racial segregation could be seen in poverty-filled urban ghettos and in the tense relationship between law enforcement and those communities. If segregated lunch counters, bus and train stations, and water fountains served as the most glaring symbols of racial discrimination in the South, the police served as the most visible declaration of racial injustice in big cities.

Malcolm, as the Nation of Islam’s national representative, [launched] a nationwide speaking tour that turned Ronald Stokes into a martyr of the larger civil rights struggle.Malcolm exploded upon hearing news of Stokes’s death. From New York, he gathered Fruit of Islam soldiers and prepared them for a retaliation mission in Los Angeles. Elijah Muhammad restrained him. “Brother, you don’t go to war over provocation,” he warned, sensing that any plans for retribution might bring down the full weight of law enforcement upon the Nation.

Malcolm listened but chafed at the Messenger’s orders and his interpretation of the events leading to Stokes’s death. “Every one of those Muslims should have died before they allowed an aggressor to come into their mosque,” the Messenger concluded. The decision stunned Malcolm and left him embarrassed by the group’s inability to defend itself.

Muhammad’s lack of action pushed Malcolm, as the Nation of Islam’s national representative, to launch a nationwide speaking tour that turned Ronald Stokes into a martyr of the larger civil rights struggle. Malcolm immediately flew to Los Angeles from New York, where he conducted a press conference describing the Friday-night melee between a group of devout Muslim worshippers, fresh from an evening service, and gun-toting police officers as an act of racist violence.

He combatted police chief William Parker’s version of events, which cast Stokes and the six other men who were shot as anti-white zealots who gleefully prayed for “the destruction of the Caucasian race.” Malcolm elicited support from the NAACP, turning the tragic circumstances into a call for a black united front.

On Friday, May 4th, one week after Stokes’s death, Malcolm held court at the Statler-Hilton Hotel. His press conference featured a poster-size photo of Stokes, proof, Malcolm claimed, that Stokes had been viciously beaten in the head with a nightstick after he had been shot. “The police went wild—went mad—that night,” he claimed.

Anticipating a grand jury’s ruling of justifiable homicide that would be released 11 days later, Malcolm prosecuted the Los Angeles Police Department and the entire criminal justice system to a wider black public, one that included civil rights activists, concerned citizens, the black working class, and elites.

Malcolm responded to what he characterized as “cold-blooded murder!” with action. He dove into the black freedom struggle with renewed conviction, forming an ad hoc coalition with civil rights groups. The black united front Malcolm often spoke of became a political reality through joint rallies with civil rights leaders, black nationalists, and local activists from everywhere from Boston to Oakland. At his most constructive, Malcolm brought together disparate strands of the black freedom movement, as he did at the Palm Gardens in New York shortly before Stokes’s funeral, where he spoke alongside James Farmer and journalist William Worthy.

Operating on little sleep, Malcolm blasted white liberals who accused him of being a reverse racist. “If it’s racism to know who my enemy is, if it’s racism to know that I’m catching hell from White America, that it’s condoned and sanctioned and backed and sup- ported by a white government, if that’s racism, well I’ll take racism above democracy and Americanism and any kind of -ism you can hand me,” Malcolm thundered.

Malcolm characterized Stokes’s death as the latest murder of a black man by the forces of white supremacy, the common enemy of black people since the bullwhip days of slavery. He compared the LAPD’s brutal history of violence against black bodies to the gestapo tactics of Nazi Germany, daring his critics to disagree.

And he deployed the briskly selling Muhammad Speaks as a political weapon to offer detailed versions of the shooting to hundreds of thousands of readers, most of whom did not belong to the Nation but devoured the paper for its lucid depiction of the wider black world. After Los Angeles, Malcolm ramped up the notion of self-defense as a central element in a global anti-colonial struggle that stretched from the United States to the Third World.

Malcolm X’s eulogy of Ronald Stokes doubled as an intellectual seminar on institutional racism in the justice system. He informed the 2,000 in attendance that despite religious, political, and ideological differences, they were being “brutalized because we are black people in America.” He decried the depiction of black anger against lynching, rape, and murder as violence, noting that the US government “doesn’t call it violence when” it “lands troops in South Vietnam.”

Black communities were living in “a police state,” he argued, demonized by law enforcement, the press, and the public. He identified Ronald Stokes as a world citizen, a recognized part of “the dark world” fighting for humanity in the face of white supremacy. In searing language, Malcolm laid out the political vision he would now follow. The death of Ronald Stokes had pushed him to his breaking point with the Nation of Islam’s policy of nonengagement in political activism and in his personal relationship with Elijah Muhammad.

His departure from the group began in earnest as he eulogized Stokes in language more befitting a political leader than a Muslim minister. His words reverberated through the Nation as well. In Chicago, Muhammad unveiled two manifestos detailing “What the Muslims Want” and “What the Muslims Believe” that included eliminating police brutality and would provide inspiration for a new generation of black activists.

Nine days after Stokes’s funeral, the New York Times published a front-page story detailing the growing amount of organized student activism, by both liberals and conservatives, on American college campuses. The story traced interest in “political and social issues” back to the sit-in movement in Greensboro, North Carolina, that launched SNCC. While conservative Arizona senator Barry Goldwater was the most popular campus speaker, two black political leaders were close behind: Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Malcolm and Martin both attracted controversy and were denied from speaking at some universities because of their political beliefs. The story reductively described Malcolm’s appeal to the black working class, well-educated African Americans, and increasing numbers of white college students attracted by the lurid “shock speeches on black segregation and supremacy.”

As the story noted, Malcolm’s political repertoire traveled far beyond religion. His cordial relationship with the venerable black labor leader A. Philip Randolph soon blossomed into an open alliance, and Malcolm forged coalitions with black nationalists on the West Coast, including Donald Warden, a gifted speaker and founder of the influential Afro-American Association, a group whose members included future Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton.

Malcolm X’s criticism of King often failed to acknowledge his militant role within the mainstream civil rights movement.As Malcolm discovered new political strength by venturing beyond the Nation’s proving grounds into new worlds of public engagement, King cultivated the southern version of the black working-class communities that helped shape Malcolm in the North. King also arrived in Los Angeles, on the heels of a speaking tour and voter-registration drive that took him to the Mississippi delta, Virginia, and South Carolina.

King stepped up his criticism of the Kennedy administration’s reticence on civil rights by publishing a combative essay, “Fumbling on the New Frontier,” in the Nation, which served as a sequel to his piece a year earlier. The essay forcefully attacked President Kennedy for failing to live up to campaign promises to desegregate federal housing by executive order. It also displayed King’s combative side, one that supporters and critics tended to ignore.

Malcolm X’s criticism of King often failed to acknowledge his militant role within the mainstream civil rights movement. While Roy Wilkins and the NAACP proceeded cautiously in acknowledging disappointment with the slow pace of the Kennedy White House, King expressed his dissatisfaction in bold strokes, chiding the president for engaging in a “cautious and defensive struggle for civil rights against an unyielding adversary.”

On this point—that white supremacy and institutional racism formed unapologetic obstacles to racial progress—Malcolm X undoubtedly agreed. He and King parted ways on solutions, with the southern preacher maintaining an obstinate hope that creative policies, legislative breakthroughs, and legal precedents, combined with spiritual and social transformation, would change hearts and minds while healing deep-seated racial wounds.

Kennedy’s reluctance to sign the housing executive order especially irked King. He argued that the Kennedy administration’s symbolic gesture of Negro cabinet appointees accomplished only the “limited goal of token integration” rather than the sweeping changes required to crush racial discrimination once and for all.

King characterized racism as “the burden of centuries of deprivation and inferior status” carried by blacks, regardless of educational achievement and class background. Kennedy, white liberal allies, and the larger American public ignored the immensity of the so-called Negro problem in favor of symbolic gestures that only stiffened the massive resistance of white southerners and their northern collaborators.

King publicly lamented presidential inaction even as he remained defiantly optimistic that mass action would allow Kennedy’s intellectual support of the freedom struggle to blossom “into passionate purpose.”

__________________________________

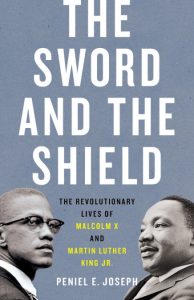

Excerpted from The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. by Peniel Joseph. Copyright © 2020 by Peniel Joseph. Available from Basic Books.