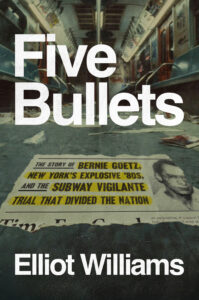

The Day Bernie Goetz Shot Four Unarmed Teenagers on the Subway

Elliot Williams Chronicles the Vigilante Crime That

Shook 1980s New York City

No matter what conclusions anyone might draw from the events of December 22, 1984, one thing is clear: from the moment Troy Canty approached Bernhard Goetz, whatever followed would permanently alter the lives of five men on the train, and with them, the entire city.

Canty, standing with his hand still clutching the hanging support, leaned close to Goetz and asked how he was doing. He later said he approached Goetz for no reason other than the fact that Goetz happened to be closest to him on the train. Accounts differ over how close Canty was to Goetz. Ramseur later said that Canty “was up in Bernhard Goetz’s face,” coming to within a foot of him. Other riders noticed the proximity; across the train, Andrea Reid leaned over to her husband and said, “Look at those four punks bothering that man.”

While seemingly innocuous, the approach would have been concerning enough for just about anybody in those circumstances to set off a red flag, or at least raise a yellow one. Even in a time and place far less intimidating than a dimly lit New York subway car in 1984, any reasonably vigilant person might have found it puzzling, if not frightening, to be approached in this way by a stranger.

As sure as there was a loaded revolver tucked into the front of his pants, Goetz was convinced that he was being threatened and was about to be viciously assaulted.

Goetz did not make eye contact with Canty. He would later say, “You’re not supposed to look at people a lot because it can be interpreted as impolite. So I just looked at him and I said ‘fine.’ And I looked down.” He said he then kept the four in the corner of his eye. In his mind, though, even the mere greeting meant trouble. Goetz remembered that his doorman at Courtney House was brutally mugged in an encounter that started with an innocent “How are you doing?” This, Goetz thought, was probably going to be no different. As he said to Nancy Grace on CNN years later, “They were just typical street thugs. You get to know them…. They didn’t even have to say anything. It was just by their positions.”

As the train shot past the Franklin Street stop, the final local stop before its destination, Goetz’s and the young teenagers’ accounts differed as to whether Canty then either asked for, or demanded, five dollars from Goetz. It was an alarming amount to request from a stranger, about fifteen dollars today. Perhaps Canty was just “aggressively panhandling” Goetz, as the act was described by William Kunstler, Cabey’s eventual attorney. Whether the words said to Goetz were a question, a demand, a violent threat, an order, or just a casual statement, we will never know. But as sure as there was a loaded revolver tucked into the front of his pants, Goetz was convinced that he was being threatened and was about to be viciously assaulted. As he told Nancy Grace, “I was very familiar with the streets of New York. I know a mugging when it’s going down.”

But according to an NYPD detective from the time, as well as others, it would have been an odd time and place for anyone, let alone an experienced petty thief, to violently mug an individual. It was the middle of the day, with plenty of bystanders nearby and no real means of escape. Even if the four had successfully robbed Goetz, they would then have been stuck on an enclosed train car, surrounded by dozens of others, until the doors opened. Unless they’d planned to mug, kill, or violently silence everyone in the train car in the remaining ninety or so seconds until the train arrived at its next stop, trying anything rash would have been foolish. Even in their lack of academic or professional sophistication, the four were likely savvy enough to know that.

The situation was certainly tense, uncomfortable, intimidating, and scary. Most urban dwellers have been in similar situations before, where they were forced to ask themselves: Is something off here? Is this guy too close for comfort? Will he leave me alone if I look away? Though risk is a reality of life in a crowded urban environment, all humans at their core want to feel safe. Furthermore, it is not healthy (and is, in fact, a sign of civic failure) if people grow so accustomed to frightening encounters that they accept them as a way of life. Mary Gant, uncomfortable at how the four were looking at her, simply avoided eye contact and buried herself in her book. It seemed to have worked. Likewise, when the young men started acting up, Josephine Holt took a keen interest in her newspaper. Like Gant and Holt, most New Yorkers would likely have figured out a nonviolent way to defuse or avoid an unpleasant encounter.

Goetz pretended he hadn’t heard Canty and asked him to repeat himself, buying time. He would later say he could not have walked away, claiming he was “surrounded” by Canty and Allen, if not all four. As Goetz would eventually tell law enforcement, “I had no intention of killing them at that time, but then I saw the smile on his face and the shine in his eyes, that he was enjoying this.” Suddenly, the encounter was no longer about money. Bernhard Goetz believed that these four young men were treating him as a plaything. At that moment, this was not just about public safety, cleaning up the streets, or being mugged. This was about pride. A white-hot rage took over Goetz. He turned around and unzipped his jacket.

Goetz typically loaded his gun with two types of bullets. The first were standard hollow-points (called “dumdum” bullets on the street), which would expand on impact with a soft target like a human body. The second were higher-powered +P bullets, a type of ammunition designed to achieve a higher internal pressure than a standard bullet of the same caliber. Both were designed to maximize the damage they could do to someone.

Goetz swung back around, now holding his gun, and said or shouted something to the effect of “I’ll give all of you five dollars!” He quickly rose and and took a “combat stance,” gripping his revolver with both hands and raising it. Goetz would later say that he fired the first shot without even aiming.

The first bullet struck Canty straight-on in the chest. Canty clutched where it hit him and fell limp to the floor, feeling his legs and arms starting to go numb. So consumed with fury, Goetz thought about using his keys to gouge out Canty’s eyes but held back when he looked down and saw fear in them. One man down.

Pandemonium.

Passengers didn’t even know if the loud bang had come from inside the train but immediately realized that something was horribly wrong. Multiple passengers referred to the gunshot as the loudest noise they had ever heard, or wondered if someone was firing off very loud fireworks in the train car. Barry Allen shouted, “Troy, are you all right?” Terrified riders lunged from their seats, dove to the ground, and began screaming and tripping over one another. Those who didn’t panic played possum. Victor Flores and Mary Gant stayed frozen in their seats, worried that if they moved the shooter might come for them next. Garth Reid saw the white shooter and black victims and wondered if a hate crime or terrorist act was playing out, with Goetz planning on killing all the black people he could find. He and Andrea grabbed their baby and sprinted through the doors at the front of the car, hoping to find refuge in the next one. In the rush, they left their stroller behind.

Goetz appeared remarkably calm amid a swirling tornado, and multiple people, including Canty, would later comment on Goetz’s equipoise. “He looked like he had the same expression he had for the whole ride” (as he fired the gun). Another eyewitness described his demeanor as “bland,” “somewhat calculating,” and “deliberate.”

After shooting Canty, Goetz turned slightly to the right and shot Allen. Whether Allen was in the process of turning and running away or stumbling in a chaotic scene in a wobbly subway car was unclear. Either way, Allen was wounded in his back, a bullet lodged between his spine and left shoulder blade, and was now jumping around and shouting about how much it burned. He said years later that when he got hit, he thought he’d been shot with a “paralyzer gun.” “My hand just went like this”—suddenly gesturing with a frozen limp hand, as if rigor mortis had set in—“I couldn’t move it or nothing.” Two down.

Multiple passengers later said that either Ramseur or Allen were desperately trying to flee from Goetz, even trying to run through the walls of the train as if being pursued by a slasher in a horror movie. Goetz then fired a third shot, striking Ramseur in the arm and chest. Three.

Cabey was in the rear of the car, either hiding or pretending to be wounded. One passenger said definitively that he saw Cabey seated and clutching a bench, with a look of terror on his face. After Goetz shot Ramseur, two bullets remained in the gun. Goetz fired them both. Though the sequence of how they were fired is unclear, within moments a panel on the train’s interior would end up with a bullet hole, and Cabey with a serious gunshot wound.

According to the police report as well as a statement Goetz made later, he thought he missed Cabey the first time he shot at him. Goetz then stood over Cabey and said, “You don’t look so bad. Here’s another,” then fired directly into his chest again. Goetz would go on to say, “I was so out of control, I would have put the barrel against his forehead and fired.” It is not clear for how long or even whether Goetz paused at that moment; several people in the car perceived that Goetz fired all of the shots in rapid succession, emptying his gun in less than two seconds, never pausing long enough to give a final message to Cabey. As Victor Flores said, “He just kept shooting until he didn’t have no more.”

Either way, there was a brief silence after Goetz was done shooting. After the final shot rang out, Canty said he could hear Darrell Cabey cry, “Why did he shoot me? Why did he shoot me?”

Five shots fired. Four men down.

Hysteria turned into shock. Piping-hot gun in hand, Goetz stood up and sat down a few times, and paced around for a bit. The police report said that Goetz checked on each of the men after shooting them. Goetz knelt down next to Canty, looked Canty closely in the face, and then shook his head and mumbled about how he needed to get out of there. All four were lying down, and according to Goetz they were “cold, no longer a threat.” They were all in some state of consciousness—breathing but still, their eyes becoming glassy.

Had Troy Canty—or, better yet, the other black men in the car, Garth Reid or Solitaire Macfoy—opened fire in a crowded train car, would they have ever been given the same courtesy?

As four struggling bodies littered the moving train car, the rest of the passengers began to wonder what they had just witnessed. Mary Gant looked to her right and saw a young black man lying on his stomach with his head toward her, eyes open. They looked at each other in silence. A male voice, which could have been Goetz, or could have been a person who had shoved her in the scrum, called to her. “Miss, are you all right? Did I hurt you? Did I hit you?”

Someone pulled the train’s emergency brake. It screeched to a halt before reaching the Chambers Street station, sparks flying from its wheels. After passengers yelled to Armando Soler, the train’s conductor, that four people had been shot, he got on the public address system and called two urgent codes to the train’s motorman: “12/7,” to request police and ambulance assistance; and the dreaded “12/8,” meaning that someone on the train had a handgun. He then ran into the seventh car and saw a calm Goetz seated there.

As Soler checked on the passengers, including the four young men bleeding out in his subway car, he asked Goetz if he was a police officer. That Goetz had the luxury of being politely asked the question is itself noteworthy; not every subway shooter would have been afforded that grace. Even the very question suggests a veneer of legitimacy for Goetz’s actions. Put another way: Had Troy Canty—or, better yet, the other black men in the car, Garth Reid or Solitaire Macfoy—opened fire in a crowded train car, would they have ever been given the same courtesy?

Goetz responded, “I don’t know why I did it. They tried to rip me off.” Soler asked if Goetz had a permit for the gun. Goetz replied that he did not. Soler then urged Goetz to give him the gun; Goetz did not respond and turned and walked away. Given Goetz’s “serene” demeanor, Soler assumed Goetz was waiting around and planning on turning himself in. Goetz saw two female passengers on the ground, paralyzed and cowering in fear. Thinking he had mistakenly hit them—another example of the extreme recklessness with which he behaved in opening fire in a crowded and enclosed space with at least one baby in it—Goetz asked them how they were doing and, with Soler, helped at least one of the two to her feet.

Goetz then had a moment of clarity. Law enforcement would be swarming the train at any moment. He knew that if he had a chance at getting away, now was his moment. It was a transit authority practice, in the event of a crime, to ground a train to prevent people, and the vital evidence they might be carrying, from getting off. Ironically, the practice enabled Goetz’s escape. With the train stopped on the dark track, he could easily jump off without any difficulty. He walked through the service door at the south end of the train car and, in a fit of panic and brazenness, jumped down to the tracks below. Gun tucked into his pants, he sprinted southbound down the tunnel, splashing through puddles as rats scurried away.

Covered in filth, Goetz reached the Chambers Street stop, climbed up onto the platform, and ran upstairs. When he emerged on the street above, at Chambers and West Broadway, he slowed down to a walk, blending into the crowd with the sweet anonymity that only a New York street in the middle of the day can provide. Every few seconds, another caterwauling light-blue-and-white Plymouth Gran Fury police cruiser would shoot by, its riders unaware that the frail-looking white guy on the corner was responsible for the underground carnage to which they were speeding. He was right there in front of them, and they had no idea.

After walking a block east to Church Street, Goetz hailed a northbound cab about a mile and a half back home, where he changed his clothes and stuffed his blue windbreaker and gun into a duffel bag. He then walked several blocks from his apartment to Olin Rent-A-Car at 21 East 12th Street and got himself a blue AMC Eagle with New York plates. He drove out of the city and, before long, over the horizon.

Bernhard Hugo Goetz of Manhattan’s West Village would become, and represent, many things in the days and weeks ahead. However, at that moment, in the middle of the afternoon of December 22, 1984, he bore a striking resemblance to a skinny, blond, middle-aged white male last seen jumping off a downtown No. 2 express train—an armed and dangerous fugitive.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Five Bullets: The Story of Bernie Goetz, New York’s Explosive ’80s, and the Subway Vigilante Trial That Divided the Nation by Elliot Williams, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2026 by Elliot Williams.

Elliot Williams

Elliot Williams is a CNN legal analyst and regular guest host on SiriusXM and WAMU, NPR’s Washington, DC, station. He has spent his career thinking about law, crime, and politics, serving as a federal prosecutor and later as a senior official at the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security. A Brooklyn-born son of Jamaican immigrants, he grew up in New Jersey and vividly recalls the powder keg that was 1980s New York. He now lives in Washington with his wife and two children.