The Dark Magic of Words: Why Fascism and Illiberalism Are So Seductive to Writers

Ed Simon Looks at Eduard Limonov, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Yukio Mishima, and Others

Christened in Gorky Oblast as “Eduard Veniaminovich Savenko,” the Russian writer, politician, and punk (in that order) adopted the novel patronym “Limonov” by the time he was living his 1970s New York City exile, a name evoking both the sourness of citrus and (“limonka” being Soviet slang for this weapon) the explosiveness of an F-1 hand grenade.

Eduard Limonov then—an appropriate nom de plume for a dissident poet arriving in 1974 New York, a metropolis of graffiti and project fires, of blackouts and serial killers. This was the city of CBGBs and the Mudd Club, the New York Dolls and the Talking Heads, Warhol’s Factory and Studio 54, repurposed Bronx turn-tables and hip-hop breakdancing, as well as the Son of Sam.

There were liberties which were possible in New York that weren’t in Leningrad, where the downtown transgressive naturally appealed to him, and Limonov’s trilogy of lightly fictionalized novels penned in Russian—It’s Me, Eddie (1979), Memoir of a Russian Punk (1983), and His Butler’s Story (1987) capture the city’s creative firmament.

“And this world needs love, the world is screaming for love,” Limonov writes in It’s Me, Eddie. “I see that the world does not need national self-determination, not governments of this or that person,” but only the “love of people for each other is necessary for us all to live.” An idealistic commitment for the poet named after a grenade, one that wouldn’t last.

As a dissident, Limonov didn’t find New York to be some immigrant heaven, but rather a cutthroat town where the Upper West Side socialites were as disaffected and atrophied as Politburo members. Still, there was ecstasy in those streets.

Transgression doesn’t always equal transcendence and liberty isn’t always found in the libertine.

“My soul and body are available to everyone,” says Edichka in the first novel. “I’ll go with you wherever I want, to the dark neighborhoods of the West Side or the opulent apartments of Park Avenue. I will suck your dick, stroke you with all my hands,” he says with Whitmanesque abandon. “I will lick your cunt….I will achieve your orgasm.”

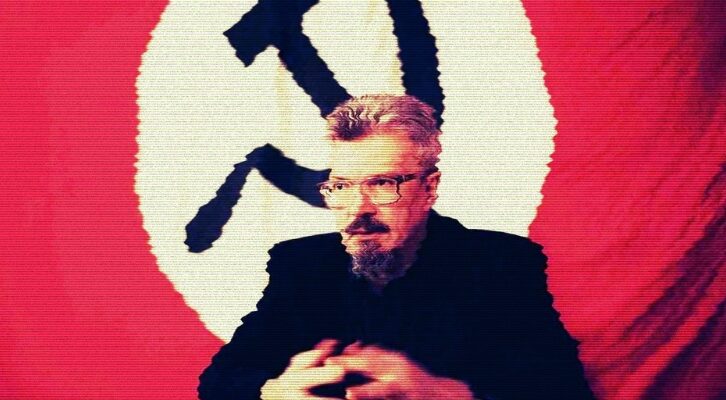

In some mirror-universe, Limonov with his circular, wire-framed glasses, his swept-back white hair and his little Trotsky goatee would be taught alongside Kathy Acker and Richard Hell, but as it was, the author went into public service (of a sort). With the collapse of the USSR, he moved back to Russia in 1991; on a May Day in 1993 he founded the National Bolshevik Party, cutting the swastika out of the white circle at the center of the Third Reich’s flag and replacing it with a hammer-and-sickle, this ideology a union of left and right, red and brown, communism and fascism.

A year earlier, he visited Serbian leader (and future convicted war-criminal) Radovan Karadžić, with Limonov firing several rounds into Sarajevo, while smiling for the cameras. The slogan which Limonov penned for the National Bolsheviks was “Yes, Death!” Transgression doesn’t always equal transcendence and liberty isn’t always found in the libertine.

In New York he was a compatriot of Truman Capote and Studio 54 founder Steve Rubell, but in Moscow he was friendly with antisemitic Duma member Vladimir Zhirinovsky and the crackpot “philosopher” Alexander Dugin (“Putin’s Rasputin”) while intoning that “Russia is Everything, the Rest is Nothing!”

The role of such a man—talented, dedicated—has to be examined closely when that same writer devotes those energies to something so ugly. National Bolsheviks, the Nazbols (emphasis on the first syllable), cofounded with Dugin though later banned by the Kremlin, was what biographer Emmanuel Carrère described as the “Russian counterculture” of the post-Cold War, the “only one.”

But a counterculture need not be an unalloyed good, of course. Subversion is a neutral value in and of itself, the question is always what’s being subverted, lest the result be the “suede denim secret police” which Jello Biafra warned about in “California Über Alles.”

Hipster Limonov’s operative mood was the smirk and the snicker, the mainstays of contemporary “Just Kidding” fascism. Though styling himself as a dissident to the then young ruler, Limonov envisioned Putin before Putin, what Peter Pomerantsev in Nothing is True and Everything is Permitted: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia describes as that “unique Moscow mix of tackiness and menace.”

Skinheads in Doc Martens with their Hitler salutes, Orthodox mystics ranting about a greater Mother Russia. Limonov would justify this as punk rock provocation, the equivalent of a swastika on Sid Vicious’ t-shirt, culture jamming agitprop learned in the Bowery and Alphabet City, but it’s ominous in 2025.

Because it wasn’t Western hypocrisy which bothered Limonov, but liberal values themselves. This was, after all, the activist arrested by the Ukrainians in 1999 after an unlicensed Sevastopol protest against the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation between Kiev and Moscow.

Had Limonov not died a year before the current war began, it’s hard not to imagine him cheering on Russian crimes. Putin may have been the writer’s opponent, but they’d both agree to what Carrère describes of Nazbol positions in Limonov: The Outrageous Adventures of the Radical Soviet Poet Who Became a Bum in New York, a Sensation in France, and a Political Antihero in Russia that “faith in human rights and democracy” is a cynical chimera based in a “certitude in bringing truth, goodness, and beauty to the savages.”

From Lefortovo Prison, where Putin sequestered Limonov on trumped up weapons charges and the almost-certainly spurious accusation he was mounting an invasion of Kazakhstan (for totalitarians broach no competition), the poet argued in his 2003 book The Other Russia—one of eight written during his sentence—that “Many types of people will have to disappear….People will die young but it will be fun. We will burn the corpses.”

Persona, gambit, conceit? Even if, there’s the risk of a mask becoming a face.

Limonov in Lefortovo shows that a persecuted author need not be a voice of tolerance and free expression, as Ezra Pound broadcasting for Radio Rome during the Second World War can attest to. Still, in a totalitarian state, writers often became martyrs of free expression, dissidents like Vaclav Havel and Alexander Solzhenitsyn, refugees such as Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky.

“The surest defense against Evil is extreme individualism,” Brodsky said at a Williams College commencement address in 1984, “originality of thinking, whimsicality, even—if you will—eccentricity.” Fair enough as it goes, but Limonov was certainly also an individual, he was original, even whimsical and eccentric.

This speaks to the Janus-faced nature of writing, of thinking of yourself as a writer, of believing yourself capable of producing literature, which is to say of reorganizing reality. It requires a narcissism that’s the hallmark of the totalitarian. What is a totalitarian leader other than an individualist taking that creed to its cruel conclusions, erasing the uniqueness of every other person into mere characters in a drama?

“There can be no doubt that distrust of words is less harmful than unwarranted trust in them,” Havel said at his Nobel Prize ceremony in 1989, and it’s this exact reason why authoritarians court writers as easily as they oppress them—because words are occult, they are magical, they make things happen.

Seven decades before Limonov fired his machine gun into Sarajevo, another poet went on a Croatian misadventure some five-hundred miles north in Rjeka, then known as Fiume. Italian novelist, aristocrat, adventurer, playwright, lover, raconteur, pilot, romantic, libertine, poet, and soldier Gabriele D’Annunzio did more than just fire a gun during the uncertain peace following the Great War—he brought an entire army, and a desire to rectify the Triple Entente’s Paris Peace Conference treaty.

An unrepentant revanchist and radical irredentist, the dandyish aristocrat with his pointed goatee and bald pate (that ironically made him look a bit like W.E.B. DuBois) assembled a phalanx of fellow veterans from Royal Italian Army’s Second Grenadier’s Regiment’s I Battalion, as well as a contingent of the elite Arditi forces, who were attracted to D’Annunzio’s heroic exploits which included dropping leaflets from a biplane over Vienna, and marched into Fiume, expelling the Allied troops then occupying the city, seeing in this detritus of the Austro-Hungarian Empire his solemn birthright.

As his biographer Lucy Hughes-Hallett writes in The Pike: Gabriele D’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War he was a “man of vehement, but incoherent, political views,” while also the “greatest Italian poet” (these things were not unrelated).

D’Annunzio was a late example of the decadentists and symbolists of La Belle Epoque, his poetry, librettos, plays, and novels dedicated to the aesthetic experience above all. His was an art which was to be lived passionately, in opposition to moralizing and didacticism, wherein in his 1889 novel The Child of Pleasure he would swoon over how there are “women’s mouths that seem to ignite with love the breath that opens them….Reddened by blood richer than purple, or frozen by the pallor of agony,” of lovers who radiate a “different beauty, happy and sad, cold and passionate, cruel and merciful, humble and proud, laughing and mocking.”

A creature who dwelt in contradiction, not least of all his politics, the dreamy poet and the man of action who most remarkably took Fiume. In his 1900 novel The Flame, which already showed the hallmarks of Friederich Nietzsche’s influence, D’Annunzio was describing Venice, but it might as well have been Fiume two decades later, for the “ancient city tired from having lived too long, the ravaged marble and worn out bells, all those things oppressed by the weight of memories…was waiting, perhaps, for a new race of Titans,” and the poet would be the leader of those Titans.

Brilliant and brave, the poet and soldier was also entirely self-absorbed, turning the Adriatic city into his own personal manuscript.

D’Annunzio established his own city-state, the Italian Regency of Canaro, with the poet in the position of Comandante. Lasting a little more than a year, D’Annunzio’s regency was a poet’s kingdom (with yoga lessons given in the town square), where one of the ten “corporations” that governed, and which included guilds of laborers, farmers, and educators (among others), was a group dedicated to the Übermenschen, poets and dreamers who were beyond good and evil, such as the Comandante himself.

Always drawn between extremes of left and right, the author incorporated elements of corporatism and syndicalism into the constitution, but it was his own potent cult of personality that was the organizing principle. Bored by policy, D’Annunzio rather saw governance as a massive theatrical project, and to that end he introduced certain novelties, including black shirts and Roman salutes, balcony speeches and martial marches, with the man known as “The Poet” and “The Prophet” taking on a new sobriquet—”Il Duce.”

A fantastical, filibustered country imagined into existence, governed not by reason but something chthonic, primal, and occult. Authoritarianism was D’Annunzio’s poetic theme and he blazed as the morning star of fascism, that nihilistic ideology the result of art for art’s sake pushed to its inhuman extremes.

What the Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima—a body-building, Samurai-obsessed, ultra-nationalist, fascist paramilitary leader that masturbated to pictures of Catholic martyrdoms—described in his 1959 The Temple of the Golden Pavilion as being how his sense of beauty contained the “darkest thoughts that exist in this world.” Mishima penned that line eleven years before his own botched seppuku after attempting to capture a Tokyo military base, shades of Limonov in Kazakhstan, D’Annunzio in Fiume.

By 1920, the Italian Army would occupy Fiume, with D’Annunzio returning to Italy where he faced no official punishment for his insurrection. Two years later Benito Mussolini would march on Rome, but not before the former convinced the later to step down from electoral politics, which required a combination of bribery and defenestration (the poet enjoyed the first and survived the second).

Before it achieved power however, fascism was D’Annunzio’s literary exercise, found within “a Hell of godless emptiness,” as he writes in Paradise Poems, for “All is a dream, all is nothingness:/the flower of the world is the asphodel,” so that citizenship, empathy, and solidarity must be subsumed, the acolyte learning to “submit…ever more to sleep’s spell.”

Myth and fantasy are what the fascist trade in, of Russia made great again, or Italy made great again, or someplace made great again (it’s always some place), but at the expense of our souls. This is the danger of an artistic temperament at its most extreme, what Nietzsche celebrated as the “Dionysian” in The Birth of Tragedy, where the artist “enriches everything out of one’s own fullness: whatever one sees, whatever wills is seen swelled, taught, strong, overloaded with strength” until all of reality merely becomes “reflections of his perfection.”

Such idealization of pure experience is an idolatry of death, since such an artist can’t envision the world beyond their individuality, can’t conceive of others enduring after the poet’s extinction. Think of Limonov’s “Yes, Death!,” of D’Annunzio’s 1894 novel The Triumph of Death.

Myth and fantasy are what the fascist trade in, of Russia made great again, or Italy made great again, or someplace made great again (it’s always some place), but at the expense of our souls,

The fascist, like the hubristic poet, imagines that the world can be recreated by the self, through words alone. A dangerous pure aestheticism in the artist who rejects empathy, because in making themselves the sovereign they believe that it is they who can decide the exception.

A Limonov, or a D’Annunzio, or a Mishima, not to mention a Goebbels (who wrote novels) or a Karadžić (who wrote poetry) may revel in illiberal transgression, in antinomian authoritarianism, but that is the result of an idolatry of aestheticism. Ever the punk, in interviews Limonov spurns “squares,” though apolitical aestheticism is anything but—it’s already chosen its side.

Basic though it may seem, if a writer is to be worth anything—regardless of their individual talent—it’s not to be for death and tyranny, but rather for their opposites.

Ed Simon

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and the editor of Belt Magazine. His most recent book is Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, the first comprehensive, popular account of that subject.