Bohumil Hrabal, the Writing Machine Who Couldn't Stop

The Czech Writer Remembers What It Was to

Fall in Love with Literature

Until the age of 20 I had no idea what writing was, what literature was. At high school I consistently fell at every hurdle in Czech language and had to repeat years one and four, so extending my adolescence by two years. . . After 20, that first solid plank of my ignorance snapped and I then fell headlong for literature and art, so much so that reading and looking and studying became my hobby. And to this day I am kept in a state of permanent euphoria by the writers I came to cherish in my youth, and I know by heart François Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, and even Louis Céline’s Death on Credit and the verse of Rimbaud and Baudelaire, and I’m still reading Schopenhauer and my latest teacher, Roland Barthes. . .

But at the age of 20 my real inspiration was Giuseppe Ungaretti, who so impressed me that I started writing poetry. . . Thus did I set foot on the thin ice of writing and the force that drove my writing was the sheer delight at the sentences that dripped from my soul onto the pages in my Underwood typewriter, and I was bowled over by the chain being strung together from that first sentence on, so I began keeping an intimate diary, my self-addressed billets doux, my self-addressed monologue combined with interior monologue. . .

And I had a constant sense that what I was writing was mine and mine alone and that I’d succeeded in setting down on those blank sheets something that was quite an honor, but simultaneously startling. Back then, whenever my mother’s friends and neighbours asked how I was getting on with my legal studies, she would just brush it aside saying that “his mind’s forever on other things”. . . And that’s how it was, back then I was obsessed with writing, a young man in gestation: the only thing I looked forward to was the weekend, when I would return from Prague to Nymburk, and the main thing was that, back then, it was so quiet in the office of the brewery and I could spend a whole two days at my Underwood, and having written the first sentence I’d brought with me from Prague, I could sit at the typewriter and wait, fingers held aloft, until that first sentence gave birth to the next. . .

Sometimes I might wait an hour or more, but at other times I wrote so fast that the typewriter jammed and stuttered, so mighty was the stream of sentences. . . and that flow, that rate of flow of the sentences kept assuring me that “this is it”. . . And so I wrote for the sheer pleasure of writing, for that kind of euphoria in which, though sober, I showed signs of intoxication. . . And so I wrote according to the law of reflection, the reflection of my crazy existence. . .

I was actually still only learning to write and my writing amounted to exercises, variations on Apollinaire and Baudelaire, later on I had a go, under the guidance of Céline, at the stream of city talk and then it was the turn of Isaac Babel and in time Chekhov and they all taught me to reflect in my writing not only my own self, but the world about me, to approach myself from inside others. . . and to know what destiny is. And then came the war and the universities were closed and I ended up spending the war as a train dispatcher and new encroachers on my writing were Breton’s Nadja and the Surrealist Manifestos. . .

I have continued to feel it an honor that I was able to write at all, that I could testify to that huge event in my life, that I was at last able to start thinking thanks to my typewriter. . .

And every Saturday and Sunday, in the deserted office of the Nymburk brewery, I carried on writing my marginal notes on things I’d seen and things that had befallen others, I was frightened, but also honored to have become, by writing, an eye witness, a poetic chronicler of the hardships of wartime, and at the same time, having spent so many years writing on that Underwood of the bleakness and brutality of reality, to have been forced gradually to let go of my adolescent versifying and replace it with a woeful game played with sentences that tended towards the transcendent. . . and so I went on setting down my self-addressed, interior monologue, but without commentary, and so, being my own first reader, I could have a sense, gazing at those pages of text, that they’d been written by someone else. . .

And I have continued to feel it an honor that I was able to write at all, that I could testify to that huge event in my life, that I was at last able to start thinking thanks to my typewriter. . . And so I carried on writing as if I were hearing the confession not only of me myself, but of the entire world. . . And I continued to see the driving force of my writing in that fact of being an eye witness and in the duty to note and set down all the things that excited me, pleasant and disturbing, and the duty to offer, by way of my typewriter, testimony not on every single event, but on certain nodes of reality, as if I were squirting cold water on an aching tooth. . .

But I saw that, too, as a divine game, as taught to me by Ladislav Klíma. . . And then the war came to an end and I completed my studies to become a Doctor of Laws, but I yielded so far to the law of reflection in writing that I took on a string of crazy jobs with the sole object of getting smeared not just by the environments themselves, but by my eavesdropping on the things people say. . . And I never ceased to be amazed at how, every weekend, in the deserted office of the brewery where on weekdays my father and his accountant would work, I could carry on jotting down the things that had befallen me in the course of a defamiliarizing week and that I had dreamed up in the arcing of my mind. . . And I went on playing like this, with a sense of having my chest rubbed with goose fat by a beautiful girl, so strongly did I feel honored and anointed by the act of writing. . .

And then it dawned that my years of apprenticeship were over and that I must snip myself off from the brewery and abandon those four rooms and the little town where my time had begun standing still. . . and I moved to Libeň, to a single room in what had once been a smithy, and so embarked not only on a new life, but also on a different way of writing. . . And then I spent four years commuting to Kladno and the open-hearth furnaces of the Poldi iron and steel works and that gradually made a difference to the way I played with sentences. . .

Lyricism became slowly regurgitated as total realism, which I barely even noticed because, working as I was next to fires and the milieu of the steelworks and the rugged steelworkers and the way they spoke, it all struck me as super-beautiful, as if I were working and living at the very heart of pictures by Hieronymus Bosch. . .

And so, having snipped myself off from my past, the scissors actually stayed in my fingers after all and, back then, I began taking the scissors to what I’d written, applying the “cutter” technique to the text as to a film. Eman Frynta referred to my style as “Leica style,” saying that I captured reality at peak moments of people talking and then composed a text out of it all. . . And I recognized this as an expression of respect because, back then, I already had my readers and listeners because I, as they put it, I had the knack of reading without pathos. . .

And so, back then, I went on writing with my scissors close at hand, and I would even write solely with a mind to reaching the moment when I could slice up the written text and piece it together into something that left me stunned, as a film might. . . And then I went to work as a packer of recycled paper and then as a stagehand and I invariably looked forward to my free time and the chance to write for myself and for my friends, and I would make samizdats of them so as actually to be a writer, a top sheet and four carbon copies.

Then I became a proper writer; from the age of 48 on I published book after book, almost falling sick with each successive book, because I’d tell myself: now they’re publishing things that I’ve thought were only for me and my friends. . .

But my readers ran into the hundreds of thousands and they read my things as they would the sports pages. . . And I wrote on and on, even training myself to think only through the typewriter, and my game now proceeded with a hint of melancholy; for weeks I would wait for the images to accumulate and then for the command to sit down at the typewriter and rattle off onto the pages all the things that by now were just scrambling to get out. . . and I wrote and kept receiving honors for my writing, although after each ceremony I felt like a nanny goat that’s just given birth to a litter of kids. . .

The most beautiful thing about literature is that actually no one has to write.

Now I can afford the luxury of writing alla prima, resorting to the scissors as little as possible, with my long text actually becoming an image of my inner self, rattled wholesale into the typewriter by my fingertips. . . Now that I’m old, I find I can genuinely afford the luxury of writing only what I feel like writing, and I observe ex post that I write and have been writing my long premier mouvement texts in time with my breathing, as if the moment I wave my green flag I start inhaling the images that are impelling me to write and then, through the typewriter, I exhale them at great length. . . and again I inhale my pop-up picture book and again exhale it by writing. . .

So it’s almost to the rhythm of my lungs and a blacksmith’s bellows that I galvanize myself and calm myself rhythmically so the act of my writing works with the motion of a grand drama, like the workings of the four seasons. . . Only now am I becoming aware that writing has brought me to the realization that only now have I pinpointed the essence of ludibrionism, which is the essence of the philosophy of Ladislav Klíma. . . I believe that it’s been only through the act of writing that, several times in my life to date, I have reached the point where I and a melancholy transcendence constitute a single entity, much as the two halves of Koh-i-Noor Waldes press studs click together, and I rejoice that, as there is less of me the more I write, so there is more of me, that I am then a permanent amateur whose prop is the one little word: Amo. . . and so love. . .

I blithely consider even the suffering and those particular strokes of fate to be just a game, because the most beautiful thing about literature is that actually no one has to write. So what suffering? It’s all just one great masculine game, that eternal flaw in the diamond that Gabriel Marcel writes about… When I began to write it was just to teach myself how to write. . . But only now do I know, body and soul, what Lao Tse taught me: that the greatest thing is To Know How Not to Know. And what Nicholas of Cusa whispered to me about docta ignorantia. . .

Now that through the act of writing I have achieved the acme of emptiness, I hope I shall be treated to some means by which finally to learn in my mother tongue, through the act of writing, things about myself, and about the world, that I don’t yet know.

__________________________________

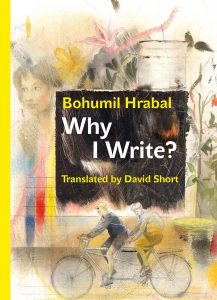

From Bohumil Hrabal’s Why I Write? (published on December 5th, 2019). Used with the permission of the publisher, Karolinum Press. Translation copyright © 2019 by David Short.

Bohumil Hrabal

Bohumil Hrabal (1914–1997) was born in Moravia and started writing poems under the influence of French surrealism. In the early 1950s, he began to experiment with a stream-of-consciousness style, and eventually wrote such classics as Closely Watched Trains (made into an Academy Award-winning film directed by Jiri Menzel), The Death of Mr. Baltisberger, and Too Loud a Solitude. He fell to his death from the fifth floor of a Prague hospital, apparently trying to feed the pigeons.