The Dead Guy

I’ve always wanted to be a superhero. I didn’t want to save the world, or even save all the children of Falasta. I just wanted to save my sister when they came to steal her imagination. If you had asked me then what kind of superhero I wanted to be, I would have said an extremely small creature, one that tracks down germs and bacteria in the bodies of children and destroys it. “Robomicrobe,” I’d call myself. I’d say all this because I was always sure that when my sister lost her imagination, she’d end up the same as all the other children around us. However much she ate she’d still feel hungry until she died. When children in my neighborhood had their imaginations stolen from them it caused brain defects. It made the brain stimulate the stomach into feeling hungry all the time. The Aharon Kibbutz Institute didn’t need the imaginations of Falasta’s children, particularly. But the institute director, Ben Moshe the Elder, had devised a way of putting these imaginations to good use. Just mentioning his name here was enough to inspire dread. The stolen imaginations were gathered together inside an artificial satellite that orbited directly above us, they called the Dabraya Star, taking its name from “the angel of death.” We couldn’t tell it apart from the thousands of other satellites and stars in the night sky, but the Dabraya Star had the ability to beam the children’s imaginations back into the past, where they took shape in the form of 3D games in front of other children—hungry, naked children with shaved heads who are said to be held in camps. Without warning, whenever they climbed into bed, holograms flashed in front of them and continued to morph and evolve until they dozed off. The next night new images took shape for them to play with. And so on. Their mothers told them, “This is why you were put here. Because you have nicer games than any other children in the world.” But the Dabraya Star above us scared the children back in my neighborhood. It made them afraid to look at the sky at night, or drove them to throw stones up into the sky when they became desperate from always being under siege. Unlike them, I wasn’t scared by objects in the night sky. In fact, I prayed every day to become Robomicrobe, so that I could plant a part of my imagination into the cells of my sister’s brain. That’s because I have more than enough imagination to go round, you see. “O Lord, make me a superhero when my sister falls ill,” I would pray. “Only when she’s ill. Turn me into Robomicrobe. So that I can cure her. After that restore me to my normal state.” But I realized that it was only by experience that you ever knew you qualified to be a superhero. So sometimes I would go to the Samra butcher’s shop and try to pick up the sheep that was tied up at the back ready for slaughter. I’d try to lift it a little off the ground and run a few yards with it. Or, for example, I would stand at the hospital gate, next to the beggars and the peddlers. Whenever I saw a boy or a girl going into the hospital with their mother or father, I would ask them enthusiastically, “Are you ill?” If they didn’t answer I would walk behind them repeating the question in various forms: “You’re ill, aren’t you?,” “My sister’s going to be ill too but I’m going to save her. If you have any brothers or sisters, maybe you’ll survive.” Most of the children would shake their heads in fear and, triumphantly and with a smile, I would say, “I knew you were ill!” This made their mothers angry and they would start insulting me. I was willing to do anything to prove to God that I had all the right qualities to be a superhero. On one occasion I jumped on a thin old man wearing thick glasses. He used to pass in front of our house every day on his way home and trip over the stump of an iron post my grandmother had planted in the ground to mark the boundary between our house and his, next door. I didn’t realize he was doing this deliberately, to force my grandmother to pull the post out. I waited for him. When he fell, he did so little by little, as if in slow motion. He went down on his hands. I thought that if I could pounce on him from behind as soon as he tripped and then twist his body around before it reached the ground, then I would save him. That meant I would be on my way to becoming a superhero. I waited for him outside the house. As soon as he went past, I came up behind him and then, as soon as he stumbled, I pounced on him. But this caused a fracture in one of the old man’s ribs and, to cover the old man’s medical expenses, my grandmother had to mortgage Mukhtar the bull, which was lame because it was missing one knee. My grandmother told me off sharply at the time, but I looked at my sister and hugged her. I told her I wouldn’t give up. Until that incident at school. We were in geography class. Suddenly I started imagining that my sister had fallen ill. I left the classroom and headed to the tank of drinking water. I plunged my head into the opening of the tank and tried to hold my breath under the water for as long as possible while imagining I was speaking to my sister. “I’ll save you. I’ll save you. You’re not going to die. You’re not going to die,” I told her. But I fainted and my body slumped into the tank. The school kids and teachers looked for me everywhere and at last they found me. I was fished out of the tank but from then on no one wanted to drink water from it, although they rinsed it out twice. After that the other kids called me “the dead guy.” “The dead guy’s come, the dead guy’s gone, the dead guy’s fallen in the tank again,” they said. And that was because I had, as they put it, passed away for a few minutes until my heart spontaneously sprang back to life. Even my grandmother called me “the dead guy.” I repeated my performance: whenever I imagined my sister had died, I went and stuck my head in the water tank. Everyone complained about me, except my sister. She never called me “the dead guy.” She didn’t like this new name. I wasn’t bothered, except that the headmaster decided to expel me for causing trouble. I told my grandmother I preferred to be close to my sister at all times. So I started waiting for her outside the school gates, and as soon as she came out, I would ask her immediately if she was well. Grandmother would wring her hands in exasperation. I told her I was behaving that way because my sister was going to fall ill soon and would die if I didn’t do something about it; I was getting ready to save her. I didn’t know how I was going to do it. But I kept praying to God to make me a superhero. I thought God would answer my prayers so long as I always behaved like a superhero. I wanted to show him how serious I was about it, show him that I wasn’t just behaving like a stupid kid. But my sister died, and I didn’t become a superhero. In fact I ended up in a glass cube. Grandmother isn’t around any longer either, or the butcher, his sheep, or Mukhtar or even the old man who, it turned out, had actually been my grandfather until he divorced Grandmother and moved into the house next door. No one. I am the last Palestinian, and that guy driving the motorbike is Ze’ev. He drives it slowly and warily, like the leader of a gang—“in case someone tries to shoot me,” he says. But if he needs to be wary of anyone, he’d do best to be wary of himself, because no one else has ever opened fire on him. Also Ze’ev has another reason: he’s not just worried someone will shoot him dead, he’s also worried they’ll set about shooting me and then be ordained “the hero” instead of Ze’ev (even though the only person who’s ever had a motive for killing Ze’ev is Ezer Banana, and he’s dead).

__________________________________

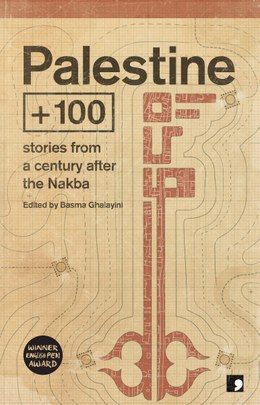

From Palestine + 100: Stories From A Century After The Nakba edited by Basma Ghalayini. Used with the permission of the publisher, Comma Press. Copyright © 2019 by Mazen Maarouf. Translation copyright © 2019 by Jonathan Wright.