The Curious Case of William S. Baekeland: Billionaire Adventurer or World-Class Scammer?

Dave Seminara Gets Mixed Up in the Subculture of Extreme Travelers

“Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life.”

–Jack Kerouac

*Article continues after advertisement

When William S. Baekeland’s name first popped into my Gmail inbox on October 12, 2015, it felt like an encounter with an elusive celebrity or a brush with a member of the British royal family. I had heard a lot about the brainy and daring young billionaire explorer from other prolific travelers I had profiled, most for a BBC series called Travel Pioneers. The series had given me a chance to meet some of the world’s greatest travelers—men who had been to not just every country in the world, but nearly every speck on the map. Their quest is to get to the hard-to-reach, virtually unvisited places at the ends of the earth and young William was the lad who was getting them where they wanted to go, or at least was promising to try. How could I resist the opportunity to profile a 21-year-old billionaire whose travel resume had floored even these hyper-well-traveled men?

Months before, I had pitched a television production company on making a TV series about the world’s top travelers and they paid me a trifling sum for the rights to my idea, with the promise of significantly more if a network bought the show they developed. But a problem emerged as they began to interview the travelers whom I had recommended: the world’s top travelers were all older, straight white guys, and many of them were retired.

“The networks want stars who are in the right demo,” said my contact at the production company, an industry veteran. “In order to sell this, we need younger travelers. And women.”

The fact that these men were venturing to fascinating, forbidden places that even geography buffs would struggle to locate on a map was apparently irrelevant. The networks wanted a Survivor cast: young multiracial people who look great in bathing suits, at least one person with a Southern drawl, and so on.

I doubled back to my network of extreme travelers in search of younger, more demographically interesting country collectors, and several made the same recommendation: William S. Baekeland. Here are some of the adjectives the country collectors used to describe him: rich, brilliant, genius, incredible, wise, remarkable. One prominent extreme traveler said in an interview that he was destined to become the world’s most traveled person.

How could I resist the opportunity to profile a 21-year-old billionaire whose travel resume had floored even these hyper-well-traveled men?

I relayed his bio to the production company and they were sold on him before they even heard his voice. What’s not to like about a handsome young billionaire with a posh British accent and time on his hands to travel to far-flung corners of the planet?

In that first email, William told me that he was working on completing the travel destination lists of two prominent clubs—the Travelers’ Century Club (TCC) and Most Traveled People (MTP), as well as his own “Baekelist” of twelve thousand world highlights he developed.

“Many of the places I wish to reach are hard, inaccessible and utterly remote,” he wrote. He continued:

To get there, you have to find your own way there. For example, I am really keen on islands. Many have no sort of scheduled service or even occasional cruises. I have to charter my own yacht or ship. At the moment for example, I am working on getting my Antarctic continent and sub Antarctic islands[’] full circumnavigation by ship worked out. Each island requires permits and planning—it is a large undertaking to get to many places.

Baekeland politely concluded that he looked forward to speaking with me, wishing me “all the best.” But he broke multiple telephone appointments and then did the same to the production company. Travelers told me that he had probably bailed because, as a billionaire, he liked to keep a low profile, and, in any case, had nothing to promote on television.

I concluded that Baekeland had better things to do with his time. After all, he was a busy young man who apparently had billions at his disposal. By 23, William Baekeland had already seen more of the world than most people manage in a lifetime. He had visited 163 countries, and his goal was to see the 30 others that he hadn’t been to. Then he’d focus on visiting every country twice. Baekeland’s passion was finding ways to get to the world’s most challenging destinations—dangerous places, disputed territories, and, most of all, remote or officially off-limits islands few could spot on a world map.

“Many of the places I wish to reach are hard, inaccessible and utterly remote.”

Rather than mingling with backpackers his own age on the beaches of Ibiza or Santorini, he frequently traveled with extreme travelers more than twice his age. He was the godfather of country collecting in that he worked tirelessly to help get the world’s top travelers to the hardest-to-get-to geographic oddities on the lists of the three biggest travel clubs: MTP, TCC, and a third called NomadMania/The Best Traveled (TBT).

Baekeland wasn’t in it for the money. William played the harpsichord and was writing a book about Norwegian Antarctica. And he wasn’t boastful—unlike most young globetrotters, he didn’t have a website or a blog to document his extensive travels. But everyone in the tight-knit community of extreme travel, including several men whom I had profiled, had heard that he was a billionaire who had inherited his fortune from his great-grandfather, Leo Baekeland, considered the father of the plastics industry for his invention of Bakelite, an inexpensive, nonflammable, and versatile plastic, in 1907.

Time magazine listed Leo as one of the hundred most important figures of the 20th century, but the family also had a spell of tabloid infamy after his death. In 1972, Barbara Baekeland, the ex-wife of Brooks Baekeland, grandson of Leo, was stabbed to death with a kitchen knife by her son, Tony. According to the book, Savage Grace: The True Story of Fatal Relations in a Rich and Famous American Family, Tony was gay or bisexual and his mother hired prostitutes and even slept with him in failed bids to convert him to heterosexuality.

William never mentioned the incident, and, in any case, his credibility among elite travelers couldn’t have been higher. Men who thought they had been everywhere would be stumped when, in his posh, upper-crust British accent, he would name-drop places like Kapingamarangi, a forgotten atoll in the Federated States of Micronesia, or Trindade and Martin Vaz, a stunning archipelago in the southern Atlantic Ocean that serves as a garrison for the Brazilian Navy.

He led these extreme travelers on expeditions he planned using his extensive diplomatic and maritime industry contacts to off-limits islands in the Pacific, like Palmyra, and to war-torn countries like the Central African Republic and South Sudan. William had no occupation, save for managing some of his family’s lands in Scotland, and was decades younger than most of the other top travelers, who had spent a lifetime building the kind of travel resume he had accumulated seemingly overnight.

His 2016 Christmas card is illustrative of his jet-setting lifestyle. It included a review of his “year in travel,” documented through a 79-photo slideshow featuring his seventh around-the-world journey, his “pioneering” adventures crossing Russia’s Northeast Passage on an icebreaker ship, landing near the summit of Mount Everest in a helicopter, and a host of other adventures from the forbidden Hawaiian island of Niihau to a Namibian ghost town and beyond.

A vegetarian—bone-thin and handsome—he looked and dressed like someone who might have been rejected from a Brooks Brothers catalog audition for being a bit too skinny and earnest. Baekeland oozed sincerity and people of all nationalities found him to be personable and good company.

In his Christmas card, Baekeland described 2016 as an “indescribably bad and difficult year.” In August, his sister Muguette died in New York. Two months later, he wrote, he lost his sister Ariadne to “weariness of life” (suicide). William asserted that his intensive travel schedule had “helped significantly with all of the challenges faced during this past year.”

He kept traveling, and, in February 2017, while on a trip to Antarctica, Baekeland’s father died, and he couldn’t get to the funeral. Other travelers said he was inconsolable, but the losses didn’t stop him from making trips to the Pacific island of Clipperton, the Central African Republic, East Timor, war-torn Syria, and Libya. He was closing in on his goal of visiting all 193 countries (as defined by the United Nations), and planned to visit his final target—Serbia—along with his mother, Lady Violette Baekeland, in October 2017 for an elite extreme traveler conference where they were set to become the first mother-son team to have visited every country in the world.

Baekeland and Lady Violette didn’t turn up in Liberland, a micro-nation that is essentially an unclaimed island in the Danube that straddles the Serb/Croat border. But many of the world’s top travelers attended the conference, and as they began to share stories and compare notes on a flurry of trips that William had recently canceled, it became clear that the young billionaire owed a number of travelers tens or perhaps hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Could a young man who barely needed to shave dupe a collection of the world’s best-traveled people? In early 2018, I became obsessed with untangling this question.

Discretion and some degree of secrecy are the norm within this small community of extreme world travelers. Many had relied on William to get them to some of the world’s hardest-to-reach destinations while maintaining discretion regarding these trips, which helped some gain a competitive advantage over their rivals. But once communication lines opened, and the founder of one of the leading clubs for top travelers started digging into Baekeland’s story, some began to doubt him.

Could a young man who barely needed to shave dupe a collection of the world’s best-traveled people? In early 2018, I became obsessed with untangling this question. It seemed like the ultimate example of the perils of wanderlust—his clients were desperate to get to the ends of the earth and were willing to do almost anything to hit their targets.

Was William a con man or just a kid with incurable wanderlust who had gotten in over his head while trying to fund his travel ambitions? The journey I took while trying to solve this riddle taught me that I have more in common with William and the mad travelers than I realized.

____________________________________________

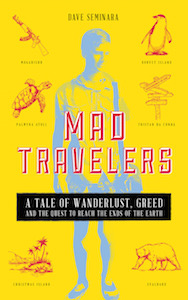

Excerpted from Mad Travelers: A Tale of Wanderlust, Greed, and the Quest to Reach the Ends of the Earth by Dave Seminara. Copyright © 2021 by Dave Seminara with permission by Post Hill Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Dave Seminara

Dave Seminara is a journalist in Oregon whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Chicago Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and a host of other publications.