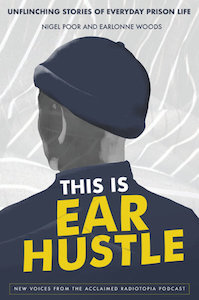

The Creators of Ear Hustle Discuss the Beginnings of the First-Ever Podcast Produced within a Prison, Distributed Globally

Nigel Poor and Earlonne Woods on Collaboration and Creative Problem Solving in San Quentin

EARLONNE

When the bus pulled into the gates at San Quentin, it looked like a college campus. I’d done time in a few prisons at that stage, but this place looked totally different. I could see guys playing tennis, jogging, and just chilling on the yard. I saw a number of geese plucking away at the grass on the baseball field. There was also a group of guys standing in front of R&R, trying to see if they knew someone getting off the bus. When they took the chains off of me and stripped me out, taking the paper clothes, the first person I ran into was my ex-cellie “CC” (whose full name is Cleveland O’Neil Campbell—I used to tease him by saying his mom gave him the last names of her three exes).

We’d been cellmates during my prior prison experience. He was an R&R worker, and the guy whose job it was to hand my naked ass a roll of clothes. He told me who was there that I would know and what San Quentin was like. All of us were placed in different holding cells. CC brought me all kinds of extra chips, cookies, and sandwiches. He also brought me new clothes that actually fit. It’s always good to know people. The next morning, I ran into all kinds of cats who I had met in prison over the years, as well as old gang associates. But it was two guys in particular I wanted to see: one was my friend Kenyatta Leal, from Centinela. He was an all-around good dude.

The other was Troy Williams, who I wanted to ask about getting into the film school. I eventually ended up seeing Troy in the shower area. He told me that unfortunately the Discovery Channel project was over, but they had left their equipment. He invited me down to the media center, where they had about eight iMac computers. The Media Lab was the heartbeat of San Quentin— the best place to be serving time—and what had drawn my attention back when I saw that documentary. It was an atmosphere of creativity, ideas, respect, bickering, love, hate, creative vision, conflicts . . . definitely fertile ground for comedy. And even though we were a group of incarcerated individuals, we were a group of incarcerated individuals who were interested in learning about how we might change the narrative about our own environment.

Troy gave me the rundown: He and seven other guys worked for San Quentin Television (SQTV), and since Troy had been in the film school, he was able help other guys learn some of the stuff that he had been taught. I already knew my way around computers. I’d used Mac computers in Centinela, where I had completed a graphic arts trade.

Very quickly I recognized that even though Troy was cool, he looked at the Media Lab as if it was his. Like he owned it. That sense of possessiveness was due to the level of trust the supervisor gave him. He had the passwords to all the computers, and the power to go film in the institution whenever he wanted. I think—in his mind—the way to protect the program was just to retain all that control. But it got to the point where everything was all about him or his vision. During meetings, we’d have these grandiose conversations about production, and the best way to create good videos or PSAs, but there were no practical lessons imparted. I soon figured out that, whatever I wanted to learn, I would have to teach myself.

We were a group of incarcerated individuals who were interested in learning about how we might change the narrative about our own environment.

The Media Lab is where I first met Nigel Poor. She started coming in to talk about photography, and how to observe everything you see in a photo and map it, which means offering your thoughts and insights. I wasn’t in the group initially, but I was always around, and Nigel seemed cool and professional. She was constantly having a meeting or working on something. Guys would share their visions with her, which would almost always be some story all about themselves. I’d see Nigel sitting there listening, her antennas up, trying to support and help guys bring their “all about themselves” visions to fruition. She’d tirelessly transcribe hour-long audio interviews, conduct crazy-long meetings, have endless, pointless conversations with the supervisor of the media center—and then, after all that, I noticed that she would often be treated like a secretary. I even saw volunteers hate on her because of how dedicated she was to her work there. San Quentin has a few thousand volunteers, of all varieties, streaming in and out every year. Guards come by occasionally to check in, but sometimes we would go hours without seeing them.

Nigel kept on bringing guys down into the studio and interviewing them. Our close friend Antwan “Banks” Williams and I used to help her with technical stuff when needed. After her show Windows & Mirrors started, people from KALW began leading workshops on production. I continued editing videos and assisting others with tech, but I was more and more present, curious about what they were doing, and eager to get involved and do a story. Troy wasn’t having it, but he paroled in 2014 and handed over the reins of SQPR (San Quentin Prison Report) to a fellow incarcerated guy named Brian. SQPR was the group of guys who were interested in creating documentary pieces about life inside. They worked out of the Media Lab, making PSAs for the prison, but had originally focused on film work. Unfortunately, Brian tried to run the program just like his predecessor—like some sort of self-designated executive director. My friend Sha Wallace-Stepter was left in charge of the radio program. Sha did a cool job with radio, but both Sha and Brian were preoccupied with other stuff.

I kept my eye on Nigel, as it became evident that she was getting fed up with people’s attitudes down there. Guys had her so pissed at one point that she was ready to walk away from the whole project and be done with San Quentin. I’d talked to her on several occasions and kept trying to convince her to stick around. I knew how frustrating the environment could be, with egos battling everywhere, but I was confident that I could change the dynamic with a few words and a bit of organization. I respected and responded to Nigel’s drive and discipline; plus she was cool as fuck.

Guys would talk shit and gossip about why she was there; some even accused her of taking advantage of them, ’cause she had gotten a grant to be able to work with us while teaching. I could see she just needed them to respect her the way she respected us. She wanted it to be a professional environment, and I did too. When it seemed like she was close to her breaking point, I decided to take matters into my own hands, and asked her to give me ninety days to change some shit. She trusted me, and agreed to holding out for a few more months.

I asked all of the radio guys how they would feel if I took over radio for ninety days. Everyone was on board, so I went and got at Sha. He was kinda relieved that I’d be taking it off his hands for a while. But as soon as he agreed, I realized that I’d be going from sideline technical support to running the department. I knew how I wasn’t going to do it (by using the iron fist approach or by taking on some lofty, meaningless title so that I could lord over anybody). Without much of a notion of what I was gonna do, I decided to allow more guys to explore what they actually wanted to do. Instead of trying to align a chaotic environment with one person’s vision, everyone with a creative instinct was welcome to pursue their own project.

Instead of trying to align a chaotic environment with one person’s vision, everyone with a creative instinct was welcome to pursue their own project.

It was during this time that Nigel and I started talking about doing a podcast. Our first one was going to be for the institutional TV channel, and I suggested to Nigel that we should get Antwan involved, especially to create the sound—one of his many artistic talents.

That first conversation about what we were going to do, I believe, was a large part of what got Nigel to stick around. To be clear, I didn’t know what the hell a podcast was, nor did I have any idea how to make one. But that seemed like an obstacle I could overcome, especially with the right partner.

People see things differently in this world. Some see no value in discarded things or people. Nigel looks more closely, sees the what if. Day after day, she showed up in the Media Lab and SAW everyone there. We weren’t invisible to her. She saw us. As somebody who spends a lot of time watching things myself, I consider her a professional observationalist—and a constant, relentless note-taker.

NIGEL

When I was growing up, if I ever told my dad I was interested in something, he would tell me to take out a lined yellow pad and “write a damn list” of what I needed to do to accomplish my goal. He instilled in me some of my more obsessive tendencies, as well as the value of repetition and persistence. I remember shooting hoops with him, and him saying, “If you want to get better, you need to do this for hours and hours.” I can’t say he made it sound particularly joyful, but he definitely got his message across: if you want to understand something or improve at it, just keep doing it over and over and over, until you succeed.

Those lessons were essential as Earlonne and I began trying to figure out our plan for our podcast. Throughout those early days, I continued with my compulsive note-taking, which has since enabled me to re-create how our podcast came to be. My notes are ways of tracing threads that eventually commingle in a curious tangle. They are my maps; without them, the tangle might prove too hard to negotiate.

The process of figuring out how to transition out of the public radio project and into a more creative, innovative project took time and patience. It had taken a while for Earlonne and me to even come together to begin speaking about it. When he was part of the crew, he was more often in the background. He came and went without being noticed, often like a phantom presence.

But I was a frequent enough visitor to the prison that over a course of weeks, months, and years we got to know each other. If there was an issue with the computers or recorder, Earlonne, or “E.,” as I came to call him, became the go-to guy. He never got flustered and was never a jerk about anything. If he couldn’t answer a question, he didn’t pretend he knew the solution; he pulled out the manual and figured it out on his own, patiently. If I ever started to get irritated, he provided a quiet, soothing presence. The more time I spent with him, the more impressed I was by his skills, in addition to his calm, humble nature.

Space is at a premium in the Media Lab. You can’t just start something new and selective and assume that others are going to respect your space. Plus, working in an environment where resources are scarce means that, if you want to get things done, you have to find a work-around. That scarcity of resources usually leads to other problems: bickering, jealousy, suspicion, gossip, and the dividing of allegiances. What started as a wonderfully creative audio project began to feel less vital to me. It wasn’t that the stories felt less important, but the way the shows were being made grew frustrating.

Every few weeks there was a new argument or complaint—each person felt that the project he was working on was the most important. That’s fine, but when time and space became a consistent issue, not everybody was ready to compromise or be reasonable. Then you had the egos: the guys that, as E. put it, needed to beat their chest and do the rooster dance. The power struggle became so toxic that people were actually firing each other . . . within the media center. It was so unnecessary. As the needless-drama quotient rose, I began to question why I was giving so much of my time and energy to an endeavor that was starting to feel unhealthy.

Earlonne recognized that I was growing tired of the negativity. He, too, got sick of being around all the infighting—it’s just not his style. So, Earlonne being Earlonne, he had a plan. He asked me to give him three months to sort it out and improve circumstances. I believed in the possibility of what we could do, and we talked about what his plan would entail: while others continued fussing around or needlessly jockeying for higher positions, we would just get to work. I didn’t want to walk away. I wanted to believe that everything from my college photography project to the communication cones, to the misdelivered mail, to teaching for the Prison University Project, to lessons learned trying to make a documentary in the prison was surely leading to something greater. I didn’t hesitate to agree to his ninety-days pledge.

We first got together to quietly hatch a new plan for a more focused and creative project that would tap into the hidden, surprising, unexpected stories of life in prison. Neither of us needed to broadcast our intentions or ask for approval or attention; we would just work it out and prove ourselves through the results. We had a pretty clear shared goal from the start: Together, with Antwan’s help, we would create a podcast that showed the commonality between those inside and those outside. We would help bridge the divide, and use voices and stories to bring people’s humanity to the surface.

On October 5, 2015, Earlonne and I met at a table in a smaller area of the lab, telegraphing to everybody else that we were having as much of a private conversation as possible in that setting. We started jotting down how we wanted to structure the podcast, what we would need, and what we wanted to convey. A few things came easily. We chose the name Ear Hustle, which is slang for “eavesdropping.” We liked it because we didn’t want the name to be synonymous with prison. We knew we wanted to figure out a way to make photos or illustrations somehow be a part of it. We also knew we wanted a distinct sound design, and some kind of intriguing theme or hook to bind together each show. We wanted it to be surprising, and not just a replaying of the kinds of stories people expect to hear out of a prison.

By nature, we’re both introverts, but we knew from the first meeting that we were going to co-host. We’d offer some banter and “yard talk” between segments to help relieve the weight of some of the tougher stories, while reinforcing the notion of inside and outside coming together to reflect on the humanity we all share. I took careful notes as we plotted out our vision, agreeing that we would always be the producers with the final say. By the end of our discussion, sitting amidst the chatter and energies of the Media Lab, our visions were aligned quickly. Now, all we needed to do was figure out where it would be recorded, who would air it, and how exactly to make a podcast. Somehow, against all reason, we walked away, confident and excited that we’d iron out such minutiae. And from that meeting came the first-ever podcast produced within a prison, distributed globally.

It would be generous to say that we didn’t know a great deal about podcasts. But we had learned something from working on the radio project, and that would be enough to get us going. Plus, we both had plenty of ideas of where we could go with it.

Somehow, against all reason, we walked away, confident and excited that we’d iron out such minutiae. And from that meeting came the first-ever podcast produced within a prison, distributed globally.

To my mind, that mutual lack of experience worked in our favor. It meant neither of us was bound by expectations of precisely how things should be done. That, in turn, meant experimenting and bringing our own creativity and sensibilities to the project. I knew Earlonne was creative because I had watched the way he solved problems, and the persistence with which he did so. He doesn’t give up until he gets it right. He thinks like an artist—meaning he is inventive, thoughtful, and creative about problem-solving. Though my work has almost always been solo, I knew instinctively that we would work well together, stepping into this unknown realm side by side.

There are very few people with whom one can truly collaborate. I often wonder and have frequently been questioned about why, and how, the two of us work so well together. It’s a tricky phenomenon to articulate. From the start, we just trusted each other. There was never any bullshit or posturing. We showed up, treated each other as colleagues and equals, and it’s never shifted from that. We also share a particular work ethic that’s rooted in an ability to listen, to recognize and support the other’s weaknesses, and to put forward the other’s strengths without having to discuss it. He can do things I could never do; I can do things he cannot, and we roll with it. We created Ear Hustle as an unlikely pair in a very tough environment by laying out our dream from the start, and not letting go.

The obstacles to that dream presented themselves immediately. You cannot count on anything inside prison. Simple daily tasks that you do outside without a thought are never simple inside. Nothing can be done mindlessly. As important as we thought Ear Hustle was, when we started it wasn’t a priority for anyone except us. There was no road map to follow. Earlonne and I had to make it up as we went along. That necessity, and our shared skills of improvising and swerving around problems, has been essential to our ongoing work.

Roadblocks became part of the process. We needed to print out scripts, but printers are hard to come by inside. Our sessions could be interrupted at any time by a prison lockdown—which would mean that I couldn’t go into the prison and would have zero contact with Earlonne. He couldn’t call me, I couldn’t call him, and we would have no idea how long it would last. Could be days, weeks, months.

When we were recording, we’d try to have what were often deeply personal interviews in a space that was almost never quiet, and almost never private. Everything was a challenge. But whenever my tank was running empty on the essential qualities—politeness, patience, and persistence—Earlonne was there to level me out so we could get back to the work at hand.

____________________________________________________________

From the book This is Ear Hustle: Unflinching Stories of Everyday Prison Life by Nigel Poor and Earlonne Woods. Copyright © 2021 by Nigel Poor and Earlonne Woods. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Nigel Poor and Earlonne Woods

Nigel Poor is the co-creator, co-host, and co-producer of Ear Hustle (PRX & Radiotopia). A visual artist and photography professor at California State University, Sacramento, Nigel has had her work has exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the SFMOMA and de Young Museum in San Francisco and the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In 2011, Nigel got involved with San Quentin State Prison as a volunteer teacher for the Prison University Project. Earlonne Woods is the co-creator, co-host, and co-producer of Ear Hustle (PRX & Radiotopia). In 1997, Earlonne was sentenced to thirty-one years to life in prison. While incarcerated, he received his GED, attended Coastline Community College, and completed many vocational programs. He also founded CHOOSE1, which aims to repeal the California Three Strikes Law, the statute under which he was sentenced. In November 2018, then–California Governor Jerry Brown commuted Earlonne’s sentence after twenty-one years of incarceration and Earlonne became a full-time producer for Ear Hustle. His efforts with CHOOSE1 continue, as he advocates for restorative justice and works to place a repeal initiative on the ballot in 2022.