The Creative Power of Rage: On Fictionalizing the Lives of Righteously Violent Historical Women

Gwen E. Kirby on Her Literary “Stabby Period”

I will never forgot when I first saw that iconic moment of American cinema: the Bennet sisters, et al., in a ballroom, pulling aside their skirts to yank swords from their garters in Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. I am not exaggerating to say that my heart fluttered, I leant forward in my seat, and the popcorn paused at my lips. For once, shit was about to get stabby and the ladies were leading the charge. I wish I could say I was twelve when I experienced this magnificent moment but I was in fact thirty and at the very start of what I hope my future literary biographer will refer to as my own stabby period.

Stabby. A word I use to make me smile, humor being my favorite defense since I’m hopeless with a rapier. A word to cover up the words beneath it—stab, injure, maim, kill—and the words beneath those words—rage, anger, fear, frustration, history. I cover my eyes from the sight of blood in a movie, can’t watch horror films, and yet when the Bennet sisters grab their swords, I find it joyful, hopeful even, as if a wrong is being righted. Austen confined her barbs to prose but in this moment, Jane and Elizabeth’s anger and fear at the prospect of a life making babies for Mr. Collins manifests in physical power. You cannot make them do what you want because look, it’s a sword. A sword means no. This sort of stylized violence, stabbiness if you will, emerges in my writing as a fascination with women from history who fight and with contemporary women who wish they could. Stabbiness makes me wonder how violence in these very specific contexts can feel affirming, even as violence is the thing being defied.

It was never my plan to write a short story collection with historical women, much less historical women who fight. And I didn’t link that project at the time to the other writing I was doing, which felt much more urgent, much more explicitly violent. On the day of the Kavanaugh hearings in 2018, I left my apartment for a walk and then found myself in a café, glued again to the testimony through my computer headphones. There didn’t seem to be an escape from the endless cross examinations or from my own blistering anger. I listened and I wrote in small bursts. I didn’t imagine it would turn into a story. I wrote about a woman who had a mouth full of fangs. Nash. Then a woman who was secretly a werewolf. Scratch. Then a woman with laser eyes. Zap. All of these woman looked normal on the outside. They all looked like easy targets and they all experienced normal indignities and terrors. And then one by one, they maimed the men who harassed them. A bloodletting of the most literal kind, I felt free in the speculative realm to wreak mayhem even as I sat quietly in that shop.

Stabbiness makes me wonder how violence in these very specific contexts can feel affirming, even as violence is the thing being defied.It took me a while to see that that same catharsis was at work in my historical fiction. At first, all I knew was that I wanted to write about women from history who broke the mold of what I’d learned growing up, when it seemed like women in the past were famous for primarily three things: sewing flags, having sex with or giving birth to famous dudes, and writing books I loved. As my short pieces piled up, though, a trend became clear: Boudicca, warrior; Mary Read, pirate; Nakano Takeko, warrior; the women in the first “emancipated” duel, not great with swords but doing their best. For all of these stories, I took liberties with history, injecting them with my own anger and often my own contemporary point of view. Eventually, I loved the contrast these fighting women made with my contemporary women. Instead of just imagining having a dangerous body, these women actually fought (and died, it should be said).

In her Art of Fiction interview with The Paris Review, Hilary Mantel says, “I would never [change a fact]. I aim to make the fiction flexible so that it bends itself around the facts as we have them. Otherwise I don’t see the point.” It already seems the height of hubris to change history or, it seems even worse to disagree with Hilary Mantel on the subject of historical fiction, but a strict adherence to the facts seems to me only one mode of writing historical fiction.

The first women hanged for witchcraft in Wales (spoiler alert) died; she did not, as I wrote her in my story, use magic to escape and sail away. And this, I think, is the power in doing exactly what Mantel warns against: freeing the historical protagonist from their time period or changing one terrible outcome for another, sometimes better, one. It doesn’t feel like a lie. I don’t imagine my reader believes that Welsh witch survived. At the very least, the reader is well aware that when women (and men) were sentenced to death for witchcraft, they died. Indeed, the reader also knows that when a man harasses a woman at a bus stop, she hopes the bus comes soon and the man doesn’t follow her. She does not bite off his hand or turn him into a pile of ash. This doesn’t make the speculative story a lie any more than the historical fiction is a lie. It’s a fantasy on top of a truth, showing both at once, highlighting how little, in fact, the fantasy asks for. Don’t hang me. Don’t bother me. The exaggeration of the reaction is practically a joke, a magic trick, not a recipe for violence but a daydream about being fearless, about living in bodies that can defend themselves or, even better, never have to.

Perhaps this simultaneous dual vision—the fantasy and the reality—is what, in the end, draws me to violence in my writing and to speculative and historical fiction. I love the contrast. I love a woman in a long dress, her corset so tight she can barely breathe, wielding a sword. I love a woman condemned to death going free. I love the power that fiction has to expose ugly truths while exploring delicious alternatives, and those are alternatives I imagine women embracing from Cassandra until today.

____________________________________________________

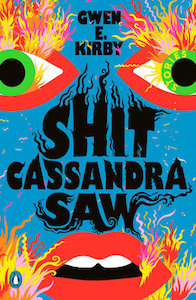

Gwen E. Kirby’s Shit Cassandra Saw is available now via Penguin Books.