The Costs—and Rewards—of a Treacherous Search for Asylum

Joe Meno Talks to Seidu Mohammed and Razak Iyal

When Seidu Mohammed was 22 years old, he was invited to try out for a soccer team in Criciuma, Brazil. Seidu had been born in Accra, Ghana, and spent most of his childhood playing soccer as an escape from the harsh economic conditions of his neighborhood, Nima. While he was in Brazil, he met another man at a gay bar and went back to his hotel with him. In the morning, Seidu’s team manager from Ghana discovered the two men together and threatened to expose Seidu back home.

Having grown up identifying as bisexual, Seidu was fully aware of what the consequences of such a threat were. In Ghana, homosexuality is punishable by a minimum of three years in prison, although individuals who find themselves accused are often tortured by police, ostracized by their families and neighbors, and sometimes murdered.

Seidu knew he couldn’t go back. Grabbing a backpack with some money and his passport he ran, leaving behind the life he had known. Days later, destitute, he met a group of asylum seekers who were heading to the US to apply for asylum.

Eight months later, Seidu presented himself at the port of entry in San Ysidro, California and was immediately placed in handcuffs and leg chains. After spending eight months in a privately-run detention facility in Adelanto, California, Seidu made his plea in immigration court and was denied for lack of evidence. Days later he was released on bond while he awaited his appeal.

In the midst of the tumultuous 2016 presidential campaign, Seidu’s appeal was denied and ICE officers contacted him to tell him he would soon be deported. Fearing for his life, Seidu traveled from Youngstown, Ohio, where he was living with his brother, to a bus station in Minneapolis on December 23rd, 2016, hoping to find a way to cross the border into Canada and apply for asylum there.

By fate or circumstance, he looked across the bus station waiting room and saw Razak Iyal, a 32-year-old asylum seeker, who happened to grow up in the same neighborhood in Accra, Ghana. Razak had run afoul of his half-siblings and a local politician in the midst of a land dispute. After a violent altercation left him hospitalized, he, too, had fled his homeland, fearing for his life.

Together the two men decided to cross into Canada on foot, having no idea of the harsh conditions and tragic consequences that lay ahead. After more than 11 hours out in the sub-zero elements, Seidu and Razak made it to Canada but at a tremendous cost. Both men lost all their fingers to frostbite. Their story made headlines around the world at a time when worldwide migration had reached an all-time high and had become a dire humanitarian concern.

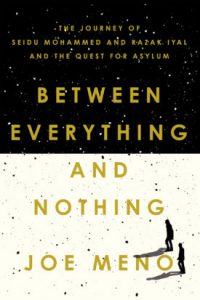

Seidu and Razak’s story is at the center of Between Everything and Nothing: The Journey of Seidu Mohammed and Razak Iyal and the Quest for Asylum. Over the last two and a half years, I’ve had the privilege to come to know both men, interviewing them in Winnipeg, where they are both permanent residents of Canada.

It has been one of the most profound and humbling experiences as a person or a writer I’ve ever had, listening to these two men talk about the physical hardships, cruelty, challenges, and moments of kindness and grace they experienced along their journey, often at the hands of complete strangers.

In the context of the worldwide impact of coronavirus, their story of survival has taken on a whole new sense of importance. As borders remain closed and unemployment skyrockets, displaced individuals find themselves trapped in a limbo of uncertainty. Ignoring fact and the advice of business leaders from his own party, President Trump has used the fear of coronavirus to further limit immigration, which poses a threat to the cultural, social, and economic life of the United States.

I spoke with Seidu and Razak via Zoom about their experience of sharing their stories for the book and the impact of the coronavirus on immigration.

*

Joe Meno: How did the idea for a book first come about?

Razak Iyal: For me, I’m a person who likes to talk. I always like talk to people. Back in Ghana, I ran an electronics repair shop and people would come and talk, to share what was happening in the community, with local politics. When I was in detention in the United States, a friend from Cameroon said you should put this all in a book, the journey you’ve been, all the places you traveled, but I never thought I really would.

Seidu Mohammed: After crossing into Canada and losing our fingers, we were interviewed and our story was on the news all over the world. I never thought we would be on television, on CNN,in the New York Times, or Al-Jezeera. Later, a film and TV producer from Canada, Sami Tesfazghi, approached us and asked if we wanted to tell our story as a movie or a book. It was exciting.

JM: Sami and his family escaped the Eritrean-Ethiopian conflict when he was a kid, before he moved to Canada. He called me and said he had met you both and that you had an incredible story to tell.

SM: It never came to my mind that my experiences would be part of a book. We just wanted people to know our story, what happened, and so we wanted to find a way tell it.

RI: I was thinking one day, even if I’m not alive, people in the U.S., and in the world and in Ghana can find out about my story. I know I am leaving something useful behind.

JM: Was it difficult being asked to relive some of your most challenging moments in order to compile the book?

SM: It’s something that needs to be told, but having to tell your story again and again, it can be difficult. I don’t want to have to think about it all the time. Fleeing from Brazil was very hard. I was outside, looking for shelter, outside for week. Detention in the US was very difficult, the way you were treated. You didn’t get enough sleep or food, and we chose to participate in a hunger strike.

It was difficult to go through the immigration process in the courtroom. It was painful to not be allowed to speak for myself. I didn’t feel like I had a chance and I was put in the same detention center with drug dealers and murderers. Talking about it for the book might help somebody so they don’t have to go through what we went through.

RI: I have to think that I’m still alive. I think how else do we move on with our lives?

Some asylum seekers died in the jungle. Some were robbed or killed by human smugglers. So here I am. I never stop thinking about what I’ve been though, so although it’s very, very difficult to describe or sometimes talk about, my experience is part of a much bigger movement, people from all over Africa, Asia, Central America.

“Even though I am sending money to my family they have been unable to leave their houses for three weeks and so everyone is worried.”

JM: What did you think when you were asked to read a draft of the book?

RI: It’s very real, the real story. One day I was sitting in my room by myself and thinking about the book and I felt like this was a dream come true.

SM: When we got the digital copy, I was like, Wow, that’s our story. I was worried how do you make a book like this interesting to read but I like how it is written, with all of the details and the things we could not talk about in other articles. One of my friends read one of the excerpts from the book, about how I traveled through Colombia and how one of the men I was traveling with died, and he said, “One of your friends died?” He had no idea. He just didn’t know some of these things.

JM: In the months since the book was completed, how have you continued to adjust to life in Canada?

RI: I finished a training program and am working at Canada Inn, in hospitality, helping in the kitchen and washing dishes, which is what I was doing back in New York.

Back in Accra, in my community, my family still faces backlash from my story coming to light, and from criticizing the government in interviews. My wife, my mom, I am worried about them. I started the process of trying to apply for refugee status for my wife. But it takes a lot of money and time to get together the documents. Because of coronavirus, like many other people, we’re now waiting. I still have the idea of opening a barbershop and hair salon with my wife whenever she is able to come.

SM: How do I live? I am free. I never in my life thought of coming to Canada. But I appreciate what Canada has done for me. At first I couldn’t do a lot of things, but now I can do most things, without thinking about it. It’s sad we lost our fingers, but we are happy we are still alive. I have been taking classes for at night school. I need three more levels for my for my high school equivalency.

I was also coaching soccer at a school for refugees and working for a translation service. I have continued speaking out about immigration and just this winter appeared at Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba to be part of a panel discussion and share my story.

JM: The coronavirus has disrupted life across the globe and has effectively shut down most forms of immigration. How have recent events affected your life?

RI: I had planned to go to Togo, Africa, to see my wife and mother. I have not seen them since I left Ghana in 2012. I am not able to return to Ghana because of the threats against my life and so we had planned to meet in nearby Togo. Because of coronavirus, everyone has to wait.

In Winnipeg, I am part of the management of my mosque and we are running a food depository and figuring out how to deliver food to people who need it. In Accra, it’s even more difficult. The government there is not helping people financially, and many people were struggling before the coronavirus. Even though I am sending money to my family they have been unable to leave their houses for three weeks and so everyone is worried.

SM: Right now, in Winnipeg, people are not working. But we are safe.

Back in Accra, the government is not helping people in need during coronavirus. My family tells me that the military has been beating people, locking them up in their houses. The government only cares about their pockets, not how to solve large problems and resolve the question of human rights.

JM: In reaction to coronavirus, President Trump has effectively ended all legal form of immigration into the U.S., including the asylum program. What are your thoughts on how coronavirus will continue to affect immigration?

SM: Not allowing asylum immigration in the US for now in order to keep people safe is okay. But in the midst of all this, there are many asylum seekers who must wait in Mexico, and they don’t know how long they must wait for.

I have a former teammate from when I played soccer in Accra who was in the process of applying for asylum and is waiting in Mexico. It might be months or years. In the meantime, people in detention should be given medical support or released from detention. Few of us know what it’s like. We just don’t know what these people have faced.

RI: Everywhere in the world, asylum seekers are facing incredible odds. I have also have a friend from Ghana who left because of similar political problems to the ones I faced and he has been waiting in Mexico. I told him to try and be patient to try and learn the language but I have not heard from him in several weeks.

The coronavirus has exposed many problems in a lot of African nations. It has made the flaws in the system very clear, especially in the rural areas. There is no source of income, no sense of possibility, so I imagine there will be an increase in asylum.

JM: What do you hope this book will do for fellow asylum seekers and refugees?

SM: What happened to us on our journey has happened to a lot of people, so the book’s been an opportunity to tell how asylum seekers and refugees are struggling all over the world.

RI: All over the globe, people are migrating. They are moving, so other people want to know about this kind of story. Before coronavirus, I was hoping we would be able to share our stories in the United States and around Canada. Still I’m very excited about the book. I’ll be happy to share this with my family and community back home as soon as I can.I’m still waiting for that moment.

__________________________________

Joe Meno’s book Between Everything and Nothing is available from Counterpoint.

Joe Meno

Joe Meno is a fiction writer and journalist who lives in Chicago. He is the winner of the Nelson Algren Award, a Pushcart Prize, the Great Lakes Book Award, and was a finalist for the Story Prize. The bestselling author of seven novels and two short story collections including Marvel and a Wonder, The Boy Detective Fails, and Hairstyles of the Damned, he is a professor in the English and Creative Writing department at Columbia College Chicago.