The Corrupt Arrogance of William Barr

Elie Honig on the Former Attorney General’s “Feigned Ignorance”

The attorney general was cornered.

It was July 2020, and Bill Barr was testifying before the House Judiciary Committee. Months earlier, in February 2020, he had taken the jaw-dropping step of publicly undercutting the sentencing recommendation made by Justice Department prosecutors who had tried and convicted Roger Stone, a longtime political ally and advisor to Trump, on charges that Stone had lied to Congress about his dealings with Russia and the Trump campaign relating to the 2016 election and that he had tampered with a witness. Even though the prosecutors had received internal DOJ authorization to seek a sentence of 87 to 108 months, Barr reached down from his perch as attorney general and publicly overruled them to seek a lower sentence—a move he would make in no other case during his tenure—prompting all four prosecutors who had obtained the Stone conviction to resign from the case.

Even though Barr had been in office as attorney general for nearly a year and a half at the time of his July 2020 testimony, it was, somehow, his first time appearing publicly before the House committee that holds primary oversight responsibility for the Justice Department. Much of the fault for this delay lay with Barr himself, who over a year before, in May 2019, had casually blown off the committee and no-showed for his scheduled testimony, the way a spring semester high school senior ditches eighth-period study hall. The rest of the fault lies with Judiciary Committee Democrats, who responded to Barr’s insouciance not by subpoenaing him but, rather, by holding a farcical empty-chair hearing and eating fried chicken on the floor of the committee room. (Get it? He’s a “chicken” for not showing up!)

But in July 2020, Judiciary Committee Democrats finally had the attorney general in the witness chair, under oath. Representative Eric Swalwell, a former prosecutor, summoned the old courtroom skills and walked Barr right into a trap.

Swalwell began: “At your confirmation hearing, you were asked, ‘Do you believe a president could lawfully issue a pardon in exchange for the recipient’s promise to not incriminate him?’ And you said, ‘That would be a crime.’” Barr agreed. Good cross-examination so far: one question, one issue, and only one possible answer. (No witness can deny his own prior testimony.) Swalwell took the next step, getting Barr to agree that he also had said that, if he saw a pardon exchanged for a recipient’s silence, he would “do something about it.” Again, solid cross; one step at a time.

“Why should I?” If any phrase perfectly encapsulates Barr’s tenure as attorney general, this is the one.

Swalwell then jumped to the bottom line. (As a cross-examination technique, this was a bit premature; he should have baited the hook more before getting to the ultimate question.) Swalwell asked, “Now, Mr. Barr, are you investigating Donald Trump for commuting the prison sentence of his long- time friend and political advisor Roger Stone?”

“No,” Barr responded.

“Why not?” Swalwell asked.

Barr unfolded his thumbs from his interlaced fingers in an interrogatory gesture and responded, “Why should I?”

Swalwell then proceeded to methodically answer Barr’s defensive “Why should I?” (This is the part Swalwell should have done before asking the big-money question at the end.) Piece by piece, Swalwell laid out a compelling case that Trump had commuted Stone’s sentence to ensure and reward Stone’s silence. A federal jury convicted Stone for lying to Congress about his contacts with Trump and the Trump campaign relating to efforts to coordinate with Russia; Justice Department prosecutors told the jury that Stone lied “because the truth looked bad for Donald Trump”; had he cooperated, Stone was in a position to expose Trump’s lies in his written responses to Robert Mueller (in which Trump claimed he did not recall any conversations with Stone about Russian connections); Trump tweeted praise for Stone’s having “guts” for not testifying against him; and Stone publicly all but demanded his reward, reminding the world that “I had 29 or 30 conversations with Trump during the campaign period. He knows I was under enormous pressure to turn on him. It would have eased my situation considerably. But I didn’t.”

Barr first responded to Swalwell’s litany of damning facts by feigning ignorance (or, perhaps, by admitting to it). He claimed he had not seen Trump’s “guts” tweet or Stone’s “I was under enormous pressure to turn on him” public statement—a claim that seemed both convenient and dubious, particularly given that Barr had previously talked publicly about Trump’s tweets on the very same Stone case.

Swalwell retorted, “How can you sit here and tell us ‘Why should I investigate the President of the United States?’ if you’re not even aware of the facts . . . ?” Barr stammered, “Because we, we require, uh, y’know, a reliable predicate before we open a criminal investigation. I don’t consider it, I consider it a very Rube Goldberg theory that you have.” (“Rube Goldberg” refers to an unduly complicated device that performs a simple task.)

So, according to Barr himself, it’s a crime for a president to issue a pardon in exchange for a potential witness’s silence. Stone lied to Congress to cover for Trump’s lies. If Stone had co- operated, he could have exposed Trump’s lies. Trump publicly praised Stone for having guts and keeping quiet. Stone boasted that he could have turned on Trump but didn’t. And Trump bailed Stone out with a sentence commutation just four days before Stone was due to surrender to the U.S. Marshals and start serving his time in federal prison in July 2020. (In December 2020, just weeks before he left office, Trump granted Stone a full pardon.) To any real prosecutor, that’s a viable criminal investigation, predication and then some. But to Barr, a man who never tried a case as a prosecutor, it’s “Rube Goldberg.”

“Why should I?” If any phrase perfectly encapsulates Barr’s tenure as attorney general, this is the one. It can be taken in two different ways, both of which reflect fundamental deficiencies with Barr’s approach to the job.

Maybe Barr meant “Why should I?” in the “I don’t see any evidence that would support opening an investigation” sense. If that’s what Barr meant, then his lack of prosecutorial chops shines through. I’ve started investigations based on less. (Remember Howie Santos and his Apple Store burglary?) Barr had plenty of evidence right in front of his face, in full public view. Yet, in a case that could have hurt the president, he chose to do nothing—just as he had done earlier on the Ukraine scandal, despite ample evidence of bribery and other crimes. An investigation of the Stone commutation stood to damage Trump. Barr didn’t even take a look.

Or maybe Barr meant “Why should I?” in the “I’m the attorney general, I do what I please, and there’s nothing you can do to stop me” sense. If this is what he meant by “Why should I?” then his response neatly captures his unique blend of arrogance and political sycophancy. Maybe I should open an investigation, but I won’t because of who might get hurt, and nobody can force me to do otherwise.

__________________________________

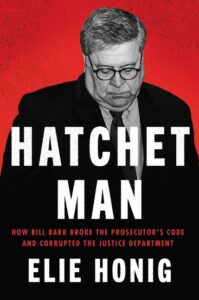

Excerpted from Hatchet Man by Ellie Honig. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Harper. Copyright © 2021 by Elie Honig.

Elie Honig

Elie Honig worked as a federal and state prosecutor for 14 years. He prosecuted and tried cases involving violent crime, human trafficking, public corruption, and organized crime, including successful prosecutions of over 100 members and associates of the mafia. Honig now is a CNN Legal Analyst, hosts podcasts and writes for Cafe, is a Rutgers University scholar, and is Special Counsel to the law firm Lowenstein Sandler.