The Comics of Aline Kominsky-Crumb: Claiming Objectification as Desire

Hillary Chute on the Pioneering Feminist Cartoonist

In 2013, when I was co-editing a special issue of Critical Inquiry, Aline Kominsky-Crumb sent me a brilliant two-page comics piece called “Of What Use is an Old Bunch?” The title refers to the nickname—the Bunch—she gives to her own character in her comics. She chose it in part because it “sounded disgusting,” she has explained. The title also refers to a story first published almost 35 years earlier, called “Of What Use is a Bunch?” In this famous, controversial strip, Kominsky-Crumb tries to answer that question about herself with statements accompanied by vignettes drawn in packed panels, in her signature expressive, wobbly hand.

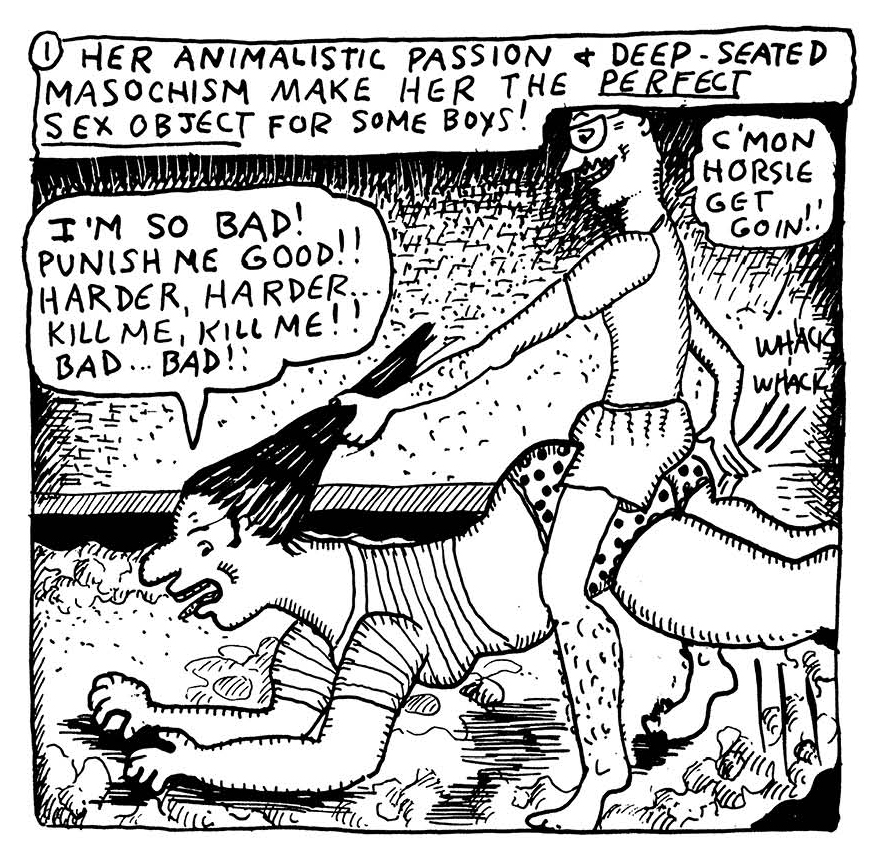

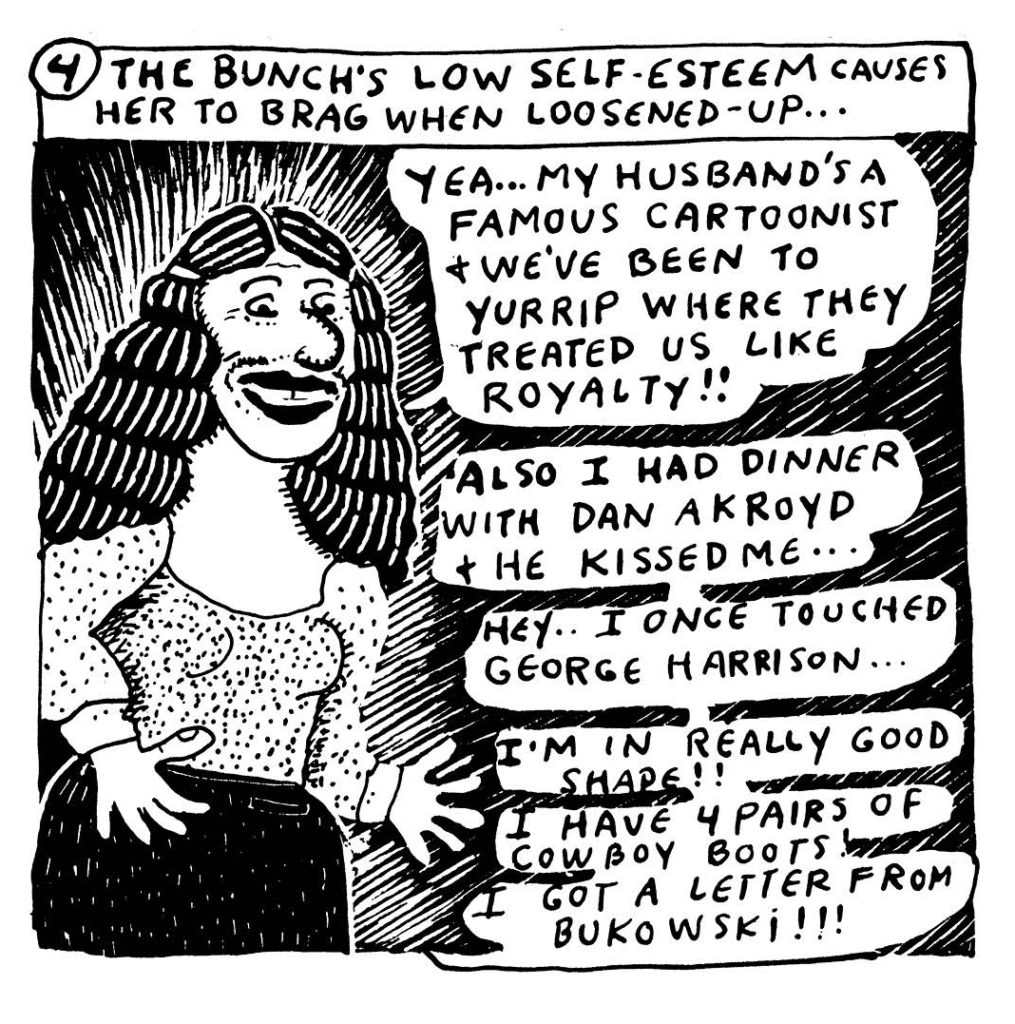

The list includes a host of negative pronouncements above illustrated examples: “The Bunch can’t draw”; “The Bunch’s low self-esteem causes her to brag when loosened up”; “When sober, the Bunch is nasty and compelled to put people down!!” After 13 such statements, Kominsky-Crumb concludes the piece with two positives: she likes to shop, and “her animalistic passion and deep-seated masochism make her the perfect sex object for some boys!” The image shows the Bunch with an open mouth, in a t-shirt and polka-dot underwear, as a man rides on her back, calls her a horsie, pulls her hair, and whacks her behind.

“Of What Use is A Bunch?” galled some readers for its apparent relentless self-deprecation, especially in the author-protagonist’s ceding to her own sexual objectification as one of the few proffered positives. But to others—including me—this piece is riveting, classic Kominsky-Crumb: it’s revealing, funny, ironic, and intimate. It also, significantly, refuses to shy away from the subject’s own desire, however unconventional or “incorrect.” Kominsky-Crumb claims her own objectification as her active desire; as Maggie Nelson points out throughout her recent acclaimed memoir The Argonauts: sexual expression is not a matter of good or bad but rather of people finding other people with whom their perversities are compatible. And Kominsky-Crumb may draw, in her approachable and scratchy hand, demonstrations of her laziness and loutishness, but she also draws a scene of sexual pleasure: “I’m so bad!” the Bunch says to the man on her back, participating with enjoyment. “Punish me good!!”

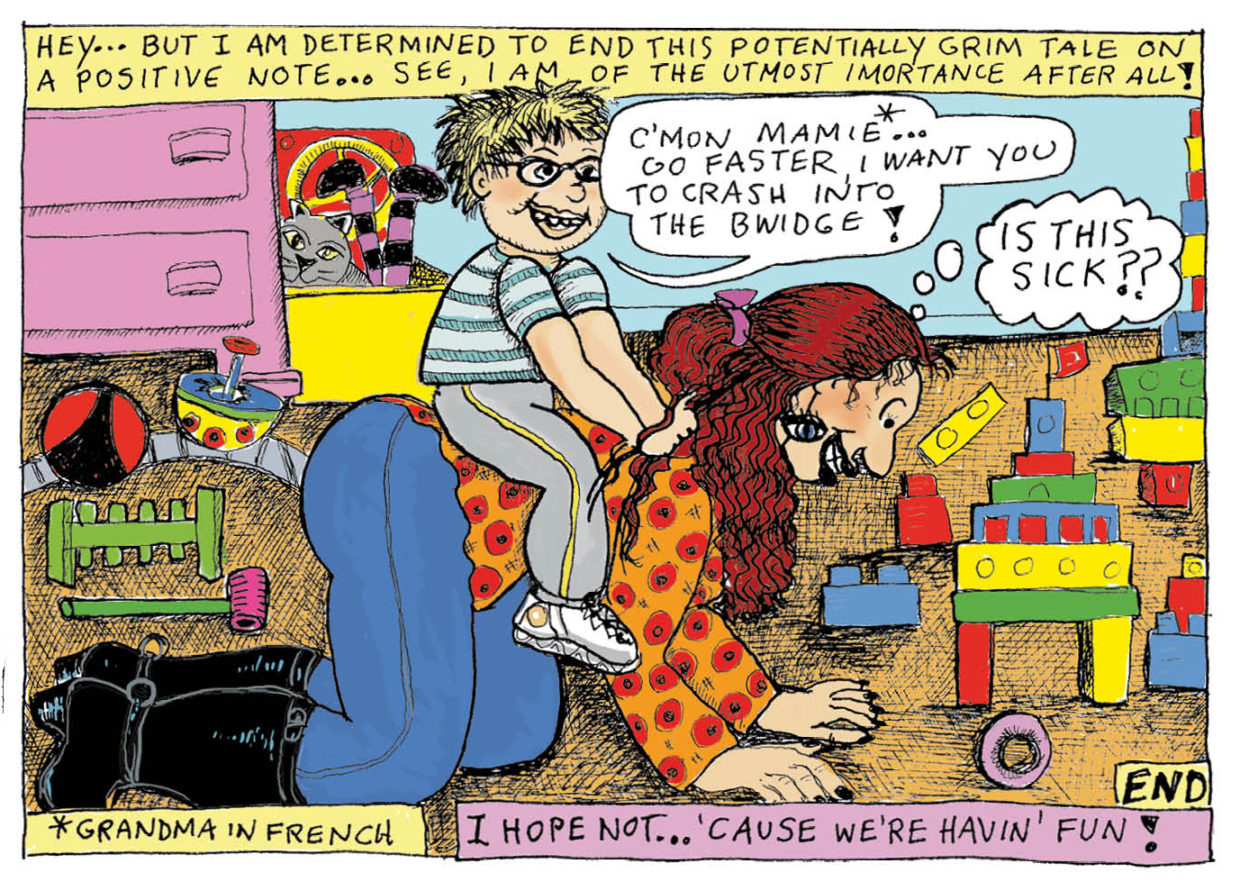

There were few stories then—in comics or anywhere else—that captured the texture and range of women’s lives, demonstrating the reality of abjection and pleasure and everything in between. Kominsky-Crumb’s comics offer a revelatory look into the complicated, contradictory lived lives of women. They changed my life and the lives of a lot of other readers, too. “Of What Use is an Old Bunch?” ends with a sweet nod to the original, in a large concluding panel that pictures Aline on all fours, with her grandson riding her back. “Is this sick??”, she wonders. “I hope not . . . ’cause we’re havin’ fun!”

Aline Kominsky-Crumb is by no means old—and she has more vigor and effervescence than most young people I know—although this is an appropriate moment to consider her four-plus decades of influence as an artist, editor, and all-around tastemaker. The kind of work she pioneered, evident from her very first published comics piece, “Goldie: A Neurotic Woman,” (in the 1972 inaugural issue of Wimmen’s Comix), has finally become more accepted and mainstream. As Huffington Post correctly pointed out in 2017 about Kominsky-Crumb’s oeuvre: “It’s a breed of unapologetic, confessional humor that young women today might recognize in television shows like ‘Girls,’ ‘Broad City,’ or ‘Fleabag,’ shows that make space for female characters who are sloppy, complex, sexual or, as they’re often described, ‘difficult.’” But while today we watch stories like these on mainstream media platforms like HBO or Amazon, in the 1970s, it was rare for a woman to put herself—the good, the bad, and the ugly—at the center of stories the way Kominsky-Crumb did. It was even rare in the no-holds-barred context of underground comics, where the men and women responsible for developing the serious “graphic novel” field we have today published their comics entirely outside of mainstream production and distribution channels—and commercial strictures. What is widely credited as the first autobiographical work in comics: Justin Green’s groundbreaking stand-alone comic book Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, about Catholic guilt and obsessive compulsive disorder, didn’t appear until 1972. Kominsky-Crumb, inspired by Green, published her own autobiographical comics work—the first such work created by a woman—later that year.

Even within the world of underground comics, which valued smashing taboos, Kominsky-Crumb broke barriers, especially with her consistent attention to embodiment. Among other groundbreaking images, “Goldie” (the title refers to Kominsky-Crumb’s maiden name, Goldsmith) pictures the bodily pain of puberty and adolescence—“I was a giant slug living in a fantasy of future happiness . . . ”; unhappy mental images of paternal erections; sexual intercourse with many different men; and masturbation with vegetables. In one panel, Goldie stares straight ahead—engaging the reader’s gaze: “I was always horny and guilty.” The story ends with Goldie recognizing that she has “a lotta putencial” (misspellings are a deliberate part of the Kominsky-Crumb universe) and moving to San Francisco, the epicenter of underground comics: “I set out to live in my own style!” The rest, as we might say, is history. Kominsky-Crumb arrived in the underground comics scene and made her way, creating out of whole cloth a funny, courageous, and tonally complex aesthetic idiom and opening the floodgates for raw autobiographical stories to take shape in comics form.

Even within the feminist comics collective that produced Wimmen’s Comix, Kominsky-Crumb’s work stood out for its striking attention to the routine functions of the female body, both painful and pleasurable—and also for producing such work under the rubric of the first person. We see this attention to capturing the everyday experience of embodiment in “Bunch Plays With Herself,” from 1975, a two-page piece with same-size frames throughout that reveals a day in the life of the Bunch: popping a pimple, scratching her behind and smelling her finger, eating a sandwich, masturbating, tanning outside, getting sunburned, napping. “My body is an endless source of entertainment!” the last panel reads. Pieces like this are confrontational about all functions of the body—it slows down to pay attention to the scratching, the smelling, and to deliver a detailed close-up panel of the Bunch’s vagina while she “plays with herself.”

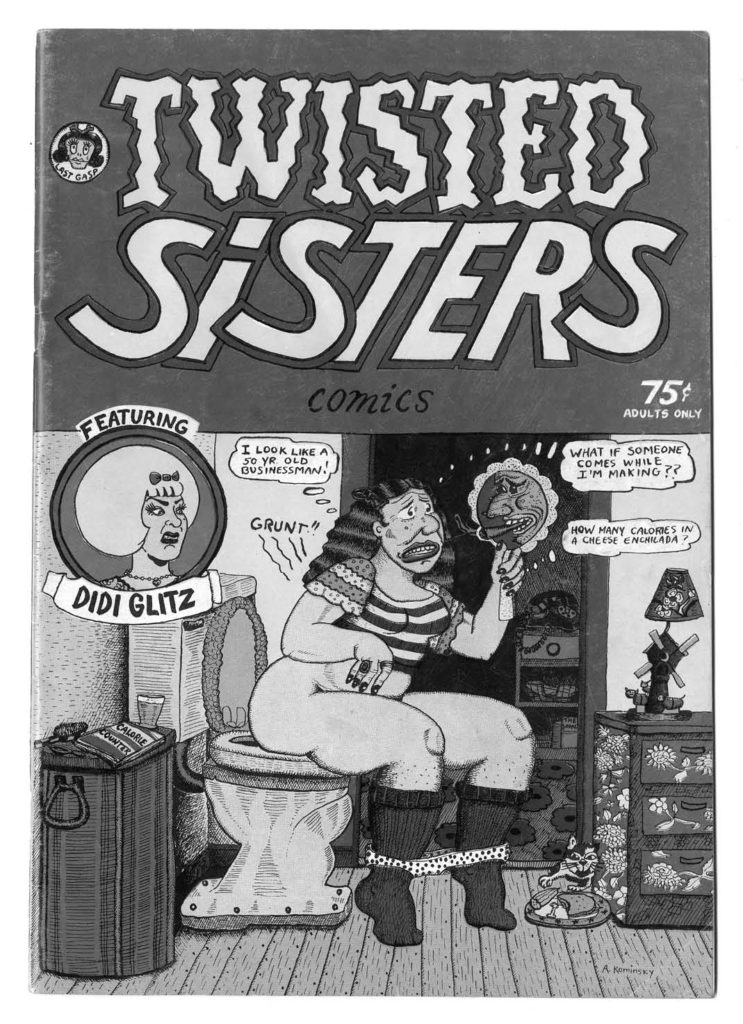

Kominsky-Crumb eventually broke with the Wimmen’s Comix collective, and founded her own title with Diane Noomin in 1976, the anthology Twisted Sisters. “They had images of women being glamorous or heroic,” she explained in an interview with Peter Bagge. “I didn’t have that background.” The infamous, and un-heroic, cover of Twisted Sisters is a drawing of herself on the toilet, looking into a handheld mirror, grunting and worrying about calories. “I would completely deconstruct the myth or romanticism around being a woman,” Kominsky-Crumb told me. “I was just vulgar and gross and everything. I enjoyed pushing it in people’s faces.” Her story about her formative teenage years, “The Young Bunch: An Unromantic Nonadventure Story,” saw print in the first issue of Twisted Sisters. In this story, as everywhere, Kominsky-Crumb mixes humor and a wry levity with dark content, particularly in the depiction of sex (rape is a theme). She claims the tradition of Jewish stand-up comedians—Alan King, Jackie Mason, Milton Berle—as a big influence, what she calls “a certain kind of Jewish fatalistic humor” that threads through her work.

Kominsky-Crumb went on to also publish her autobiographical stories in underground publications including Arcade: the Comics Revue, founded by Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith (1975–1976); Power Pak, her own solo comic book (1979–1981); and Weirdo (1981–1993), the acclaimed, influential anthology founded by cartoonist Robert Crumb and edited by Kominsky-Crumb for seven years. With Crumb, whom she married in 1978, she also founded the titles Dirty Laundry and SelfLoathing, which featured the couple’s collaborative confessional strips; their collaborations started appearing in The New Yorker in 1995, and many were collected in their book Drawn Together.

*

Love That Bunch, her first book, appeared in 1990, a loosely chronological grouping of 29 stories that begin in her childhood and end in her forties. All of the stories engage the nexus of gender, sexuality, and subjectivity.

When I interviewed her about ten years ago, Kominsky-Crumb pointed out that her work has always been completely unsuccessful. Twisted Sisters, she said, had “no impact . . . We had no feedback; it sold hardly any copies.” She went on, referring to her comic book titles as well as to Love That Bunch: “I had no success ever. In any terms . . . I never had any kind of feedback from the fine arts scene or the comics world.” At least in part, this situation seems to be a reaction to her particular style. Kominsky-Crumb has a fine art background. She grew up in Woodmere, in the Five Towns area of Long Island, which she describes as materialistic, striving, and “horrible,” but started taking art lessons and painting at age eight. As a young teenager, she became enamored with New York City’s museums, and inspired by avant-garde idioms. One panel from Love That Bunch shows her as a teenager staring at a Cubist painting thinking, “If I can figure this out I can escape from Long Island!!” Kominsky-Crumb attended Cooper Union in New York City for a semester before moving to Tucson to earn a BFA in painting at the University of Arizona.

Despite her training with paint and canvas, it was comics that would become the medium in which Kominsky-Crumb first realized her artistic vision. She eventually fled the (often male– and Abstract Expressionist-dominated) world of art school and painting for the world of San Francisco underground comics publishing, which felt more open, porous, urgent, and truly experimental, a realm where personal stories, and women’s personal stories, could find shape. But while her comics work operates in conversation with fine art idioms—she is particularly influenced by German Expressionist artists such as Otto Dix and George Grosz—the lack of mimetic realism in her drawings have coded to comics fans as unskilled rather than expressionistic; as “bad” rather than communicating emotional urgency and immediacy in the febrility of the line and distortion of perspective. Kominsky-Crumb is also influenced by painters who delved into the dark and the personal, such as Alice Neel, Frida Kahlo, and James Ensor, along with Matisse, Picasso, and Cézanne—painters known for eschewing correct perspective and academic realism in favor of expressivity and essence.

Kominsky-Crumb has a thin, wavering line, and her panels, while much of the drawing lacks realistic detail, are regularly crammed and crowded, especially in reproducing pattern and texture. When Kominsky-Crumb first started collaborating with Robert Crumb to produce comics, many fans of his work—known for its fluid crosshatching and masterful control—found Kominsky-Crumb’s shaky hand, which can look so uncrafted, an insult; they wrote nasty letters.

Yet, an art critic as powerful and exacting as The New York Times’s Roberta Smith understands the value of Kominsky-Crumb’s style. In 2007, reviewing a 33-year retrospective of Kominsky-Crumb’s comics at the Adam Baumgold Gallery in New York, Smith wrote that Kominsky-Crumb “excels at the drawn-and-written confessional comic . . . Her clenched, emphatic style echoes German Expressionist woodblock in its powerful contrasts of black and white, and her female faces . . . have a sometimes uncontainable fierceness.”

While Kominsky-Crumb has described her comics style variously as ugly, primitive, tortured, and scratching, for many readers, including me, its roughness, irregularity, and “imperfection” is welcoming, charming, and every bit as (if not more) compelling than “fine rendering.” Her images feel vital, fluid, and direct. One way to think of her style is as importing a tradition of painting into a younger tradition: comics, built on print. (We can understand this happening in the “ratty line” aesthetic of another cartoonist starting out in the 1970s: Gary Panter, who also trained in fine art and exhibits in both comics and painting today.) For his part, Robert Crumb—who Kominsky-Crumb explained “got” her work instantly and is her best fan, realizes that “fine rendering doth not an artist make,” despite being held up by his own fans as a paragon of fine rendering. In the introduction to the collected volume of Dirty Laundry comics, Crumb addressed his wife directly: “Fine rendering can be a trap, a web of clichés and techniques. Your work is entirely free of such comic-book banalities . . . You remain amazingly impervious to the pernicious influence of all cartoon stylistic tricks . . . which is mainly why so many devotees of the comics medium are put off by your stuff.”

“She has inspired countless cartoonists and readers, especially women and girls who weren’t used to seeing multifaceted representations of their everyday lives on the page—or anywhere—reflected back at them with such honesty.”

But not all of them. While in comparison to other major, terrain-shifting figures in contemporary comics, Kominsky-Crumb’s work has remained in the shadows, there have always been ardent admirers for whom her influence has been profound. Her comics stories and the landmark Love That Bunch opened up the field of comics to be more confessional—more open both stylistically and in terms of content. She has inspired countless cartoonists and readers, especially women and girls who weren’t used to seeing multifaceted representations of their everyday lives on the page—or anywhere—reflected back at them with such honesty. The cartoonist Phoebe Gloeckner first discovered Twisted Sisters as a young teenager.

It changed her life and the kind of groundbreaking artist she in turn would also become, unflinchingly revealing sexuality, as does Kominsky-Crumb, in registers including both degradation and delight. (While both cartoonists make heavy use of anamorphism, especially when it comes to the male body, Gloeckner has a devastatingly realistic hand, in contrast to Kominsky-Crumb’s messier expressive hand.) On a panel I organized in 2012 with Kominsky-Crumb, Justin Green, Phoebe Gloeckner, and Carol Tyler, Gloeckner told Kominsky-Crumb of Twisted Sisters: “I memorized that comic . . . I read it so many times and every time I would get something more out of it.”

At age 15, she sent Kominsky-Crumb fan mail, and the two eventually met. When Gloeckner’s book The Diary of a Teenage Girl (2002) was recently made into a feature film, Aline Kominsky-Crumb appeared as a fairy godmother-like character, an animated drawing interacting with actors on screen. To note just one of countless other cartoonists for whom Kominsky-Crumb led the way, Alison Bechdel, of Dykes to Watch Out For, Fun Home, and Are You My Mother?, has noted that the Crumb/Kominsky-Crumb collaborations “were very much an influence in terms of trying to be as honest as I can, especially about sexual stuff.” And Kominsky-Crumb—in her hugely significant role as editor of Weirdo from 1986–1993, during a key time for the establishment of comics as an important contemporary form—extended her taste and legacy by nurturing the careers of artists like Gloeckner, Julie Doucet, Carol Tyler, and many others (the majority of whom would go on to be represented in the two important book volumes titled, like the comic, Twisted Sisters).

There has been an uptick of critical attention in the past ten or so years to the significance and ongoing appeal and relevance of Kominsky-Crumb’s comics (she also has a separate life as an exhibiting artist working in a variety of media, which has also drawn important attention—where her style appears very different from what appears in her comics—which for her is a direct, confessional form).

Kominsky-Crumb and I have known each other since 2005; she has even welcomed me into her home in France—and taught me yoga the one and only time I’ve ever done it, with an enthusiastic group of French women and her as my very rigorous teacher (I couldn’t lift a shirt on or off my body without pain for days). I write about her in my books Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics, which opens by examining her legacy, and Why Comics? From Underground to Everywhere—the latter in a chapter about comics as a space for picturing the illicit and uncensored, whether fantasy or reality. The title of a recent scholarly book—“How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs, by Tahneer Oksman— is a direct quote from Kominsky-Crumb’s sad, hilarious 1989 story “Nose Job,” about standards of beauty growing up in her Jewish enclave of Long Island. Kominsky-Crumb was also featured in Graphic Details: Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews.

And with more and more regularity, Kominsky-Crumb’s work is being taught in the space of the classroom. One of my former students, a current college senior who wrote a final paper that examined Kominsky-Crumb’s work, among others, for an art history class, wrote to me: “Her scratchy drawing style and the distorted anatomy of her characters remain unlike anything I’ve ever seen . . . Her work uniquely marries images of lust and repulsion and brings visibility to the ‘disgusting’ aspects of women’s bodies and desires. It’s thrilling to read Kominsky-Crumb, to see her defy all censorship, and track how she inspired many fearless female artists to come.” Other students have commented on the humanity in her work, with its textured, messy surfaces, and lively, uncontainable line.

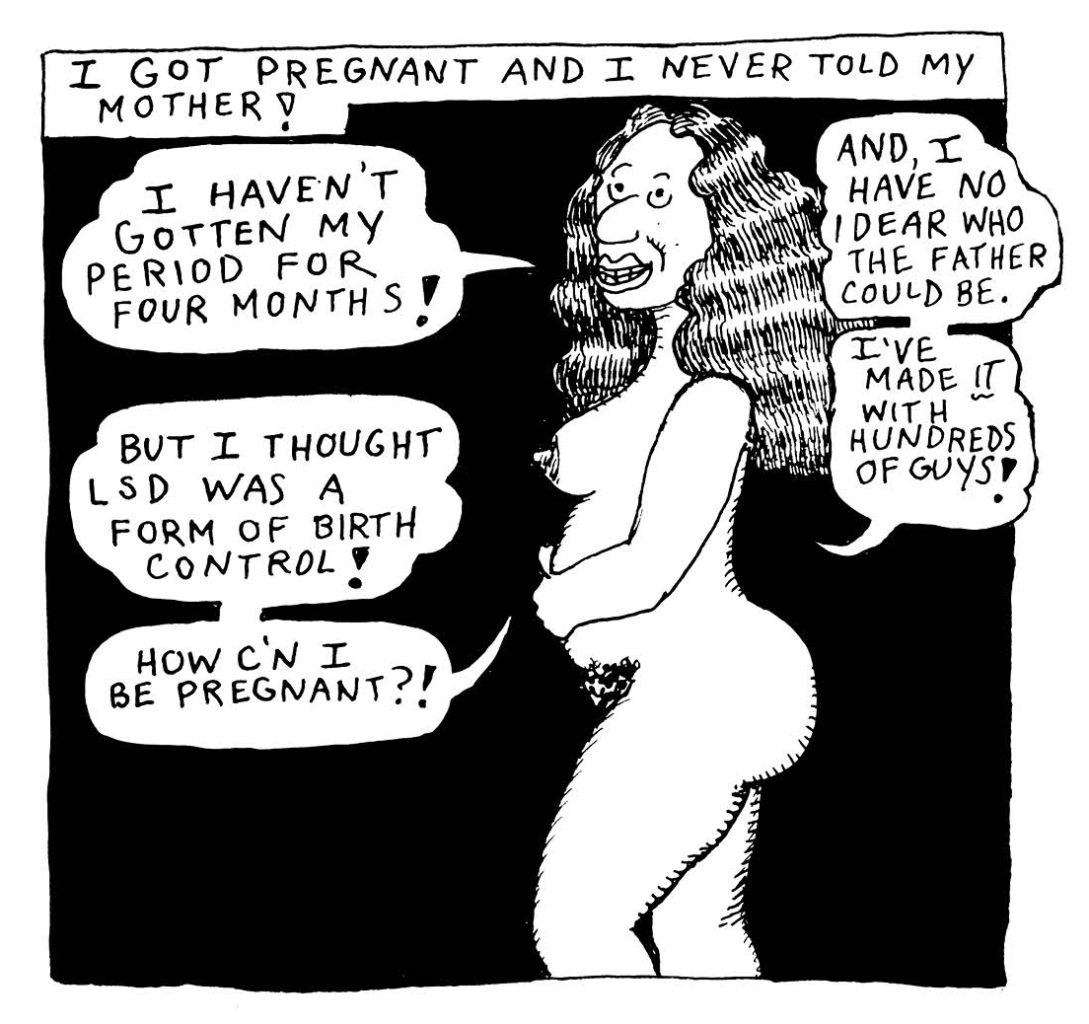

Kominsky-Crumb shies away from nothing, tackling some of America’s most persistent taboos. In the long story “My Very Own Dream House,” she reveals how she got pregnant at 18 (“But I thought LSD was a form of birth control!”) and gave birth to a healthy baby boy in 1967, whom she put up for adoption. “I had wild sex and took lots of drugs right up until the minute I was ready to give birth,” she writes in Need More Love, her 2007 graphic memoir. In these days of heightened scrutiny and huge moral judgment about women’s maternal behaviors, admitting to doing “lots of drugs” during pregnancy is not a conventional fact to publicly disclose, especially because, here, it is resolutely not in the form of asking for an apology, and side–steps shame altogether.

Kominsky-Crumb has also published, in collaboration with Robert Crumb, a story about her experience having a face lift: “Saving Face,” which appeared in The New Yorker in 2005. Another taboo: detailing your plastic surgery. Her mother, Kominsky-Crumb told me, was horrified: “How could you tell everybody that? You’re supposed to hide it! No one can tell! You look gawgeous!” She explained to me, “I want to liberate people so that they can feel free to talk about it and not feel bad about stuff they decide to do . . . that was, to me, one of the most radical things I ever drew.”

And I was, even knowing them, honestly shocked and fascinated in the winter of 2017 to discover that Kominsky-Crumb and Crumb tackled the topic of their own wealth in a confessional comics story for Harper’s. (Crumb has said that Kominsky-Crumb inspired his work to be more confessional.) Coming at the subject of money from this privileged perspective is, truly, one of America’s last strong taboos, and they dove right into it. “Aline & Bob in Troubles With Money” opens with the news that original Crumb artwork has sold for 2.9 million dollars, and the story is about advice the couple gets for how to handle their influx of money. Drugs, plastic surgery, money: the sense that there is nothing Kominsky-Crumb won’t share in her art—the unfettered access she gives readers— is exhilarating.

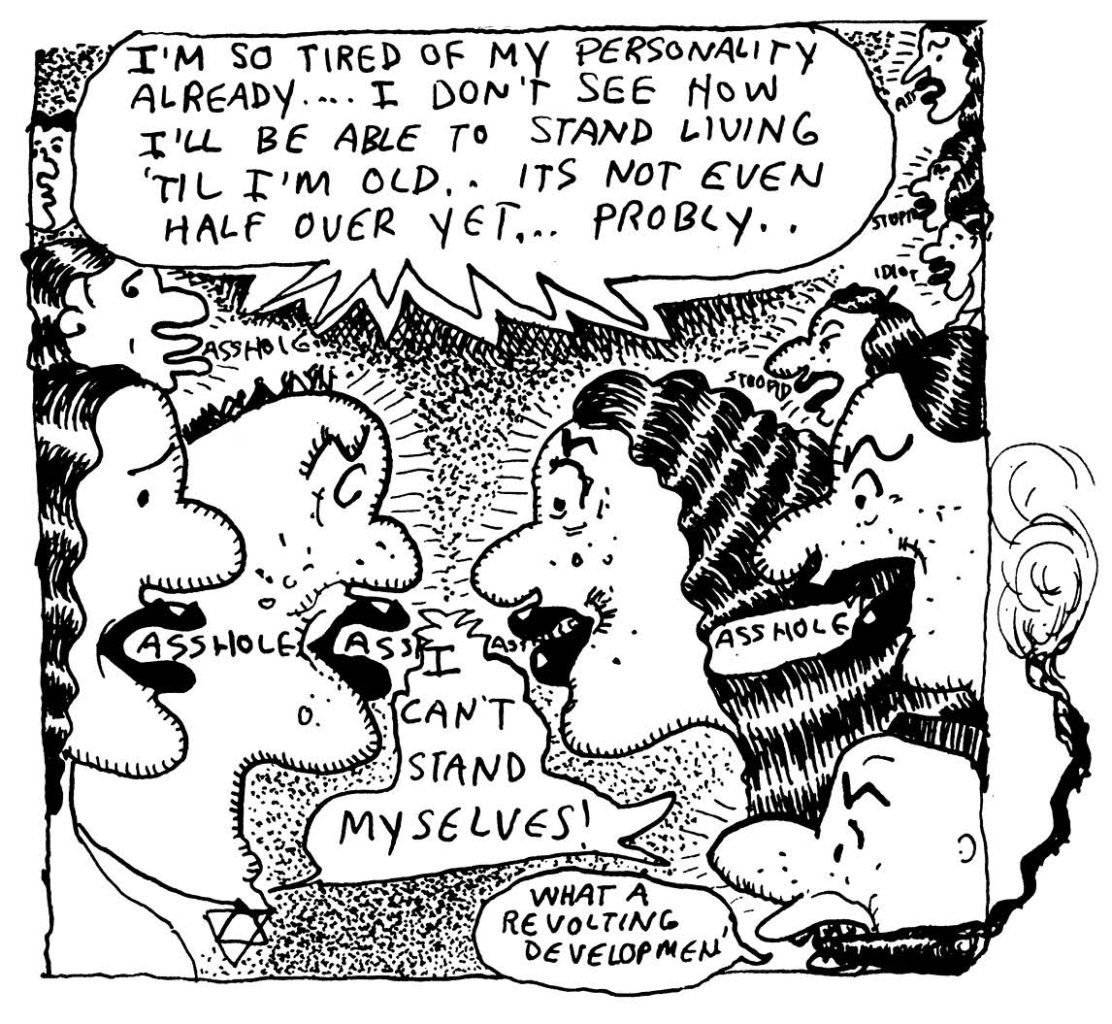

Kominsky-Crumb’s comics are shot through with a brave sense of possibility, both in her sensitive and humorous approach to her subjects, and her view of the always-fluid self. In one of my favorite panels, from Love That Bunch’s “Up in the Air,” Kominsky-Crumb draws a frame jammed with 11 different versions of herself, with various lipstick and hairstyles (one is even a man smoking a cigar), facing and insulting each other. “I can’t stand myselves!” several of the selves declare in a shared speech balloon.

“I’m so tired of my personality already.” “Asshole!” one hilariously calls out to another. None of them is the one “real” self—they all are. As opposed to being depressing or self-deprecating, this non-continuous, unfixed view of self and proliferating potential, undergirds Kominsky-Crumb’s work in the most positive way: it models how selves shift and change with time—embodying contradictions in order to keep on living life to the fullest.

__________________________________

From Love That Bunch. Copyright (c) 2018 Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Used with permission of D+Q/Hillary Chute. Foreword (c) copyright Hillary Chute.