The Comical, Ominous Power of a Shakespearean Mob

Robert McCrum Explores Popular Revolt in Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s world connects with our world through commensurate emotions. The young Shakespeare may have been fascinated by kings and their courts, but he also began to address popular politics. It was here, exploring the “mind” of the common people, that he began to become Shakespearean, testing another kind of modern hazard: popular passions, and the power of the mob.

As an Elizabethan, he was familiar with the fragility of the state, and its vulnerability to external threat or internal dissension. His contemporaries feared the Wars of the Roses as much as the Armada. In 1589–91 (the dates are disputed), soon after his arrival in London, a metropolis buzzing with obstreperous, polyglot energy, he began to address “the nature of the times deceased” from the commoners’ point of view. His first history play, Henry VI, seethes with the transgressive thrill of popular revolt, as well as the Machiavellian, psychopathic frenzy of Richard Gloucester:

I that have neither pity, love, nor fear.

Indeed, ’tis true that Henry told me of . . .

I have no brother, I am like no brother;

And this word, ‘love’, which greybeards call divine,

Be resident in men like one another

And not in me – I am myself alone

–3 Henry VI, 5.5.69-84

The threat of Richard’s demonic ambition is one thing. The frenzy of the mob is something else, but Shakespeare treats it with a mix of laughter and dread. The grammar-school boy from Stratford is nervous of popular disorder among the illiterate classes, and uneasy about street protest, but he seasons his account of Jack Cade’s uprising with flourishes of demotic humor.

In 2 Henry VI, his rebels are Anglo-Saxon yahoos to their marrow. They want to trash metropolitan society and terrorize the toffs (scrap learning, liberate the gaols, burn books, and let the city conduits “run nothing but wine”). “The first thing we do,” declares an anonymous butcher, in a famous line, “let’s kill all the lawyers [4.2.78].”

In Shakespeare, English protest becomes second cousin to football hooliganism, some distance in ideology and rhetoric from the barricades. The rabble-rouser in chief, John (“Jack”) Cade, a rebellious clothier, is less a pocket Trotsky than a pub bore:

There shall be in England seven halfpenny loaves sold

for a penny, the three-hooped pot shall have ten hoops,

and I will make it felony to drink small beer. All the

realm shall be in common . . . and I will apparel them

all in one livery, that they may agree like brothers, and

worship me their lord.

–4.2.67–77

Cade’s followers are all too familiar—butchers, tanners, weavers and brewers—from trades that Shakespeare lived amongst in London. Two class-conscious rebels (Bevis and Holland) enter the scene whingeing about the “threadbare” state of the commonwealth. Holland declares, “Well, I say it was never merry world in England since gentlemen came up.” The two men spy some “hard hands.”

Holland: I see them! I see them! There’s Best’s son,

the tanner of Wingham—

Bevis: He shall have the skins of our enemies to make

dog’s leather of.

Holland: And Dick the butcher.

–4.2.23–7

At this moment, Shakespeare is not so far from a rowdy Saturday night on an English high street. His account of Cade’s rebellion has an immediacy we recognize: it is philistine, anti-clerical, vicious, vulgar, and bullying. “Dost thou use to write thy name?” demands Cade, interrogating Emmanuel, a hapless clerk cornered by the mob. “Or hast thou a mark to thyself, like an honest plain-dealing man?” Fatally, the clerk answers, “I thank God I have been so well brought up that I can write my name.”

All: He hath confessed – away with him! He’s a villain

and a traitor.

Cade: Away with him, I say, hang him with his pen

and inkhorn about his neck.

–4.2.101–9

From such casual brutality, which will put the audience into the antechamber of their worst nightmares, it’s a short step to a full-throated assault on those traitors who “speak French.”

Cade’s vicious xenophobia strikes a deep chord of chauvinism among his Kentish followers. If “the Frenchmen are our enemies” there can be only one logical conclusion:

Cade: Can he that speaks with the tongue of an enemy

be a good counsellor, or no?

All: No, no – and therefore we’ll have his head!

–4.2.168–72

This crowd is different from the politically motivated plebeians of Julius Caesar (1599) or Coriolanus (1607–8). Cade’s men are a “rascal people, thirsting after prey [4.4.50]”; their motivation is a weird mix of the mercenary and the mindless; his followers have a peasant hatred of ink and paper. When their class enemy, Lord Saye, is finally cornered, Cade denounces him as “filth” in resonant and topical abuse:

Cade: Thou hast most traitorously corrupted the youth

of the realm in erecting a grammar school…

appointed justices of the peace to call poor men

before them about matters they were not able to

answer.

–4.7.30–40

When the doomed Lord Saye tries to defend himself with a desperate quip—”tis bona terra, mala gens”—Cade’s furious response is “Away with him! Away with him! He speaks Latin [4.7.55].”

Later, in Coriolanus, Shakespeare would return in middle-age to the clash of the people with the state. For the moment, in these early histories, he connects the bleakest tragedy to the experience of humanity: the subordination of ideology to human appetites becomes his Shakespearean message. By the time 3 Henry VI was packing audiences into the playhouse during 1591–2 (the dates are unclear), he was manipulating the narrative of history to his dramatic purposes, cutting and transposing sequences, revising and reimagining old scenes, but also coining speeches that went straight into the bloodstream of contemporary conversation. Shakespeare always had a great line in great lines. When Richard, Duke of York upbraids the indomitable Queen Margaret, he never spoke to better effect:

O tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide!

How couldst thou drain the life-blood of the child

To bid the father wipe his eyes withal,

And yet be seen to bear a woman’s face?

–1.4.138–41

These were phrases that would haunt Shakespeare throughout the next decade of his London literary career, his polemical first appearance in the literary record as “Shake-scene.”

__________________________________

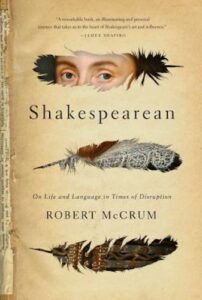

From Shakespearean: On Life and Language in Times of Disruption by Robert McCrum. Used with the permission of Pegasus Books.

Robert McCrum

Robert McCrum was born and educated in Cambridge. For nearly twenty years he was editor-in-chief of the publishers Faber & Faber, and then literary editor of the Observer from 1996 to 2008. He is now an associate editor of the Observer. He is the author of Every Third Thought, My Year Off, Wodehouse: A Life, six novels, and the co-author of the international bestseller, The Story of English.