“The Cat’s in the Bag, the Bag’s in the River”

What were we meant to be feeling at the movies in the 1950s on hearing a line like this? What do we feel now? What is this insinuating rumor about the cat, the bag, and the river getting at? How did movies make such magic out of masked meanings?

We looked at the screen, and things there seemed so real or emphatic—the men, the women, the sky, the night, and New York. In Sweet Smell of Success (1957) you believed you could sniff the black-and-white stink of the city. Wasn’t that in the contract as light ate into film’s silver salts? But the things depicted were also elements in a dream—nothing else looks like black-and-white. And because we believe dreams have inner meanings, not meant to be understood so much as lived with, we guessed there might be a secret within the facts. Was it just a gorgeous, repellent mood in Sweet Smell, or was a larger odor hanging over the film?

“The cat’s in the bag, the bag’s in the river,” Sidney Falco says to J. J. Hunsecker as information or promise, even as endearment. Those two rats play a game together called bad mouth. In 1957 in Sweet Smell the line had the click of hard-boiled poetry or of a gun being cocked. It said that some secret business was in hand, cool, calm, and collected but also dirty and shaming until you dressed it up in swagger. We were sinking into rotten poetry. I felt for that cat, and wondered if its death was being signaled; but I guessed the scrag of wet fur was alive still—it was a secret and secrets don’t die, they only wait. The very line said, What do you think I mean? And that’s what the best movies are always asking. Sometimes you revisit those 1950s movies and feel the cat’s accusing eyes staring at you through the bag and the rising river.

Some people treasure Sweet Smell of Success because it’s so unsentimental, so gritty. I don’t buy that. Long before its close the story becomes tedious and woefully moralistic. It shuts itself down, and then the wisecrack lines are stale garnish on day-old prawn cocktail. Admit it: after sixty years, a lot of “great” films can seem better suited to museums than packed places where people want to be surprised for the first time, now. In museums, as on DVDs, the films can seem very fine, yet not much happens while you’re watching except the working of your self-conscious respect. But power in a movie should be instant and irrational; it grabs at dread and desire and often involves more danger than contemplation.

Sweet Smell is that good or grabby for at least half an hour—and in 1957 that came close enough to horror or fascination to alarm audiences. Perhaps that’s why the scabrous movie had to ease back, turn routine, go dull, whatever you want to say. Would it have been too disturbing for the movie business—which includes us, the audience—if Sweet Smell of Success had gone all the way and let its cat out of the bag?

As written first by Ernest Lehmann, then rewritten by Clifford Odets, and directed by Alexander Mackendrick, Sweet Smell is set in the old newspaper world of New York City. J. J. Hunsecker is an indecently potent gossip columnist on the New York Globe. The hoardings in the city call him the Eyes of Broadway, with the image of his cold stare and armored spectacles. At the time, there was talk that Hunsecker was based on a real columnist, Walter Winchell. That’s not incorrect. But how many now know who Winchell was then? Whereas a lot of us still respond to the smothered hostility in Burt Lancaster and react to the gloating tension he has in the lm with Tony Curtis.

Lancaster played Hunsecker; his own company (Hecht-Hill-Lancaster) produced the movie. So Burt was in charge, and he is filmed throughout the story as a monarch who sits still and orders the execution of others with the flicker of an eye or a hushed word. That verdict will be passed finally on Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), a scuttling press agent who survives by getting items into Hunsecker’s column and so can be engaged to do whatever ugly deeds J.J. requires. A refined, codependent slavery exists between them: J.J. smiles and Sidney smiles, but not at the same time. It is the toxic pact between these two that makes the film disturbing for at least thirty minutes—but it might have been a greater film still if it could have seen or admitted that their mutual loathing is the only thing that keeps them from being lovers.

This was not admitted in 1957, and no one can blame a commercial movie of that era for lacking the courage or even the self-awareness that would have been so direct about a destructive homosexual relationship. If Burt had felt that subtext, his company would never have made the picture. But Burt the man and the actor cannot resist the allure of the secret. He looks at Sidney and at his own position like a charmer looking at a snake and seeing danger. Yet Sweet Smell plays out finally as one more melodrama of good people and bad people—the way Hollywood liked to tell us the world worked. The radical situation of the lm is that Sidney fears and needs J.J. while the columnist despises but needs Sidney. There’s no room for conventional affection, let alone love, but dependency is like cigarette smoke at the nightclubs where the two rats live. And it reaches poetry in the vicious zigzag talk that joins these men at the hip.

They know each other like a married couple.

The talk seems lifelike—you can believe you are hearing two cynical professionals whose venom is ink; the insults feel printed. But it’s hard for movies to stop at that. In the conspiracy of close-ups and crosscutting, and in the pressure to hold audience attention, the talk becomes musical, rhythmic, a self-sufficient rapture, and even the subject of a film.

Sidney goes to the 21 Club, sure that J.J. will be there, in his element. They know each other like a married couple. J.J. is at his table, holding court—he is a little like Vito Corleone at the start of The Godfather, but not as warm or amiable. Hunsecker is receiving a U.S. senator—a weak officeholder he has known for years—a groveling talent agent, and a blonde woman the agent is touting (and providing for the senator’s pleasure). The blonde is named Linda James. She maintains she is a singer. She is played by an actress named Autumn Russell who had a dozen movie credits before fading away; she is good here as a woman past youthful freshness, attractive yet desperately preserved, painfully available, and about to be humiliated.

Sidney sits down at the table, beside but a little behind Hunsecker. J.J. begins to order him away, but Sidney has a password, a way into J.J.’s need—he has something to tell him about Hunsecker’s sister. So the powerful man relents and Sidney stays. Then Miss James, trying to be pleasant, wonders out loud if Sidney is an actor.

“How did you guess it, Miss James?” asks Hunsecker, scenting revenge.

“He’s so pretty, that’s how,” she responds. And let it be said, Tony Curtis in 1957 was “pretty,” or a knockout, or gorgeous… The list of such words is not that long, and it’s nearly as problematic now as calling a woman “beautiful.” Let’s just say “pretty” fits, even if Sidney is torn between pleasure and resentment at hearing the word.

Then Hunsecker speaks—and in a few words we know it is one of the killer speeches of 1957.

Mr. Falco, let it be said, is a man of forty faces, not one, none too pretty and all deceptive. See that grin? That’s the charming street urchin’s face. It’s part of his “helpless” act—he throws himself on your mercy. He’s got a half a dozen faces for the ladies, but the real cute one to me is the quick, dependable chap—nothing he won’t do for you in a pinch, so he says! Mr. Falco, whom I did not invite to sit at this table, tonight, is a hungry press agent and fully up on all the tricks of his very slimy trade!

That speech is as cruel as it is literary. It helps us recognize how uncasual or nonrealistic movie talk can be. Of course Hunsecker is a writer, though it’s easier to believe he dictates his column instead of putting pen to paper. But the speech relishes words and their momentum. In life, it was one of the speeches that Clifford Odets hammered out on his typewriter in a trailer parked on a Manhattan street hours ahead of the shooting. Odets had been a revered playwright in the 1930s, the husband or lover to famous actresses, and here he was, at fifty, a Hollywood writer and rewriter for hire, doctoring a screenplay for immediate performance. He knew self-loathing from the inside; observers said he was “crazed” by the shift in going from being the next Eugene O’Neill to just another script doctor. Yet Odets was good enough to build to this moment: as he concludes his assassination, Hunsecker picks up a cigarette, and says, quietly, “Match me, Sidney.”

This is an ultimate humiliation; it is the blade slipping between the bull’s shoulder blades; but it is a proposal, too, or an admission that a terrible wounding marriage exists between the two men, one that cannot be owned up to or escaped. The line is poison for Sidney to taste, and Tony Curtis has played the scene, in close-up, like a man with a sweet tooth for poison, on the edge of nausea. (Later on in the film, Hunsecker tells Sidney he’s “a cookie filled with arsenic.”)

But even a destroyed wife can sometimes get a line back. “Not just this minute, J.J.,” Falco answers, and now we know there is a level between them, beneath professional cruelty and self-abasement. It is a horrible kind of love. Hunsecker smiles at the refusal, as if to admit that the wretched Falco can stick around.

There is more talk like this, and in 1957 it was courageous or even reckless: the film was never a popular success—it had rentals a million dollars less than its costs, so Burt the businessman suffered, which meant others would feel the pain. One obvious risk in the film was giving offense to real Hunsecker-like figures and undermining the integrity of what was still called “the press.” But there’s a deeper implication in the scene and the talk: these two men need each other; they might exchange insult and subjugation forever. Indeed, as an audience we don’t want them to stop talking.

Alas, Sweet Smell cannot act on that realization. A complicated plot intervenes. J.J. is obsessed with his sister, Susan. This is asserted, but never explored: does he simply need to control her, or does he have a physical desire for her that he cannot express or admit? It should be added that there is no other woman in Hunsecker’s life. He is disturbed that Susie seems to be in love with a young jazz musician, Steve—maybe the cleanest, whitest, dullest jazzman in all of cinema. These two characters, played by Susan Harrison and Martin Milner, are embarrassments who drag the lm down. This is not an attack on the actors but despair over the concept that lets the lm dwell on them. Why is J.J. obsessed? We never discover an answer. I don’t necessarily want to see his incestuous yearnings; I accept his need for power and fear in others. But I want chemistry between J.J. and Susan if the threat of losing her is to be dramatic.

As it is, Sweet Smell degenerates into a tortured intrigue in which Sidney contrives to frame Steve on drug charges, just to make Susan turn against her guy. This leads to an ending in which two bad men get their just desserts. But that is banal and lacks feeling for “the young lovers,” who trudge off together into a new day. We do learn more about Sidney’s conniving nature, and the film becomes a showcase for Curtis. (That he was not nominated for his work speaks to how far Sidney unsettled Hollywood.) But we do not get enough of the two caged men clawing at each other with spiteful words. I don’t think anyone could contemplate a remake of the film today without seeing that there has to be a gay relationship between columnist and press agent, a reliance that excludes the rest of life.

As the film ends, Susie has found the strength to leave her brother. “I’d rather be dead than living with you,” she says. The odious cop, Kello, has beaten up Sidney on the street and carried his limp body away. Is he dead? Or would it be possible for J.J. to come down to the street to reclaim the broken body, carry it upstairs, and put it in the room left free by Susie’s departure? That is not an enviable future for a very odd couple. Maybe Sidney lives in a wheelchair, crippled and needing to be looked after. Just so long as he can exchange barbed lines with J.J.

This is less film criticism—as in a review of a new film—than a reflection on the history of the medium and the way a dream evolves if it is potent enough. I can find no evidence that anyone on the picture intended the undertone I am describing, or was aware of it. I am confident that director Mackendrick and writer Odets were not homosexual, though I’m less sure that they didn’t understand the possibility of that relationship and see an underground life in the casting. Tony Curtis (born Bernard Schwartz in 1925) really was a very good-looking kid, though as a Bronx boy and then a young man in the Pacific war (in submarines), he was only ordinarily good-looking. It was in the late 1940s, as he thought of a show business career, that he started working hard on his looks and his body, and when he felt people in the neighborhood were thinking he might be gay.

In those late 1940s—and still today—there is a widespread feeling that a lot of people in show business are gay. That notion exists above and beyond the fact that there are more homosexuals in show business than in most other professions. Curtis was a fascinating case, with a well-earned reputation as a ladies’ man, with six marriages and six children.

In watching pretense we acquire a deeper sense of our reality but a growing uncertainty over our psychic integrity. What else are movies for?Curtis was also funny, candid, and quite bold. He could sit there on screen as Sidney while other characters considered how “pretty” he was. Many lead actors of that era would not have stood for that—I’m sure Lancaster would not have sat there, absorbing it (which doesn’t mean he was deaf to the undertones as he administered the lashing). Curtis grew up in the movie business with a corps of very good-looking guys, many of whom were clients of the agent Henry Willson, who cultivated gay actors who did not come out of the closet on screen—one of them was Rock Hudson, a contemporary of Curtis’s at Universal.

Maybe most important of all, Curtis had the courage to play Josephine in Billy Wilder’s radical film, Some Like It Hot. How much courage? Well, it’s fair to say that Jack Lemmon played Daphne in the spirit of farce and slapstick. It’s not likely, watching Some Like It Hot, in 1959 or now, to believe that Daphne is a girl. But Curtis went for it. Josephine is an attractive woman. Curtis is candid in his book, American Prince, about the shyness he felt in wearing female clothes and then being on show in front of the crew. “After all these years of putting up with guys coming on to me and hearing rumors about my own sexuality, dressing like a woman felt like a real challenge to my manhood.” So he told Wilder that Josephine needed better clothes.

Not that it matters now, but I don’t believe Tony Curtis was gay, ever. Of course, that would have nothing to do with his ability as an actor to imagine or pretend to gay experience. And if Curtis was that good then he was admitting millions of people in his audience into the same experiment. One principle in this book—and it has been of enormous influence in our lives as a whole—is that in watching pretense we acquire a deeper sense of our reality but a growing uncertainty over our psychic integrity. What else are movies for? We thought we were identifying with characters for fun, but perhaps we were picking up the shiftiness of acting—for life.

The case of Burt Lancaster is more complex. He was married three times, and he had five children. But we are past believing that such credentials settle all interests. The best biography on Lancaster, deeply researched and written with care and respect by Kate Buford, does not believe he had an active gay life. That book was published in 2000. On the way to a celebration of its publication at Lincoln Center, I had dinner with an old friend, George Trescher, a man who did nothing to conceal his own homosexuality, and he assured me that in fact Lancaster had led a gay life. Later still, some documents were released from the F.B.I. and the Lancaster family that did not name names but that revealed that Lancaster had often been “depressed,” that he was bisexual, and that he had had several gay relationships, though never on more than a short-term basis.

With that in mind, you might look at Lancaster’s strangest film, The Swimmer (1968), directed by Frank Perry and taken from a John Cheever story. It’s a fable about an apparent Connecticut success, Ned Merrill, who takes it into his head to swim home one summer Sunday by way of all the pools owned by his acquaintances. Cheever, who had a tormented gay life, watched the filming with awe and amusement, as Burt, at fifty-five, in simple trunks, made Ned’s way from sunlight to dusk and dismay. Why did they make that movie? you’ll wonder. Because Burt wanted to do it.

For much of his career, Lancaster was called a he-man or a hunk. Trained in the circus and proficient as an acrobat, he loved athletic and adventurous roles in movies for which he frequently did his own stunts. As a boy, I thrilled to him as Dardo in The Flame and the Arrow (1950), about a twelfth-century Robin Hood figure from Lombardy. His sidekick in that picture was played by Nick Cravat, a circus partner who kept company with Burt for decades. They made nine films together, including The Crimson Pirate (1952), with Burt as an archetypal grinning rogue, beautiful and physically commanding, in what went from being a straight pirate adventure to a camp romp in which Lancaster is blond, bright, and comically cheerful—in other words, the hero is a parody of himself.

There was another Lancaster, darker and more forbidding: you can see that actor in The Killers, Brute Force, and Criss Cross, and he emerged fully as Sergeant Warden in From Here to Eternity. That Lancaster became a good actor, but for decades he was determined to stay athletic and heroic: as late as The Train (1964), when he was fifty, he was doing his own stunts. But his work in Sweet Smell is the more interesting for being so repressed. Was he at ease like that? Orson Welles had been the original casting as J.J., but Welles was in a run of ops so Lancaster the producer elected to play the monster himself. He made the role in a way that would have been beyond Welles. It’s in Hunsecker’s stealth and stillness that we feel his evil—or call it a darker inner life than Burt was accustomed to showing. Only a couple of years before Sweet Smell, he had played with Curtis in Trapeze, a conventional circus film that took advantage of his own physical skills.

Tony Curtis reported in his book that Lancaster was often very tense during the filming: he was at odds with Mackendrick, so that they sometimes came close to physical conflict. In one scene, Mackendrick wanted Burt to shift over on a bench seat to let Curtis sit at the table. Burt insisted that Hunsecker would not have moved for anyone—it was a good insight—and he nearly fought the director. Mackendrick was taking too long; the picture’s costs were mounting. But the physical actor in Lancaster was both determined on and pressured by the role’s tensions.

The film’s composer, Elmer Bernstein, said, “Burt was really scary. He was a dangerous guy. He had a short fuse. He was very physical. You thought you might get punched out.” Yet Lancaster was supposedly in charge, as both character and producer. Was he afraid of his own film commercially? Did he bridle at his required stillness? Was he in control of Hunsecker’s blank rage? Did he guess that Tony Curtis had the more vivid role? Or was he oppressed by the implications of the film’s central relationship? Did he feel the movie was a plot against him? These questions are not just gossip; they enrich one’s experience of J.J.’s paranoia. Lancaster’s authority and Hunsecker’s power are twinned and destructive.

If we see a gay subtext in Sweet Smell, then the hobbled nature of its women characters becomes clearer. It is not just that pliant singer on a senator’s arm. Susan is an emotional wreck, attractive in outline but drained of romantic confidence or stability. At one point Sidney tells her to start thinking with her head not her hips. Hunsecker has a secretary who has no illusions about him. Sidney has a girl who is his humbled slave. There is a well-drawn betrayed wife (nicely played by an uncredited Lurene Tuttle). And then there is the Barbara Nichols character, Rita, an illusionless hooker so degraded she will do whatever Sidney requires of her. There isn’t a woman in the lm with appeal or self-respect. This bleak elimination of heterosexual potential is part of the dankness in Sweet Smell and one more contrast with the exhilarated sparring between the male leads. Hatred or antagonism is their idiom, and we can’t stop hanging on the tortured double act.

__________________________________

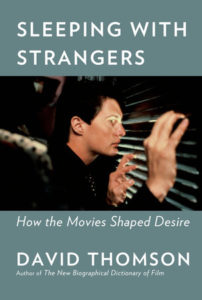

From Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire. Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright © 2019 by David Thomson.