The idea of the “rock god” was born in 1971 in an article in the Edwardsville Intelligencer, a newspaper in Illinois, USA. But David Bowie had long believed in such beings, and now he was about to make one, become one, and kill one.

There was once a singer named Vince Taylor, whom Bowie had befriended in the mid-1960s. “He had a firm conviction that there was a very strong connection between himself, aliens and Jesus Christ,” recalled Bowie in 1996.

“Those were the three elements that went into his make-up and drove him. And one night he decided he’d had enough. So he came out on stage in white robes and said the whole thing about rock had been a lie and in fact he was Jesus Christ. It was the end of Vince, his career and everything else.”

“One girl, crushed to impotence, swung a despairing face toward us. ‘If only I could touch him,’ she gasped.” Two thousand years earlier, a woman said of Jesus: “If I only touch his cloak, I will be made well.”

Even before Vince Taylor, Elvis Presley and Little Richard had sent the younger generation into rapture. In 1957, the magazine Melody Maker first used another holy word, declaring: “Rockers-and-rollers fought to lay hands on their idol.”

The object of their devotion was Bill Haley: “One girl, crushed to impotence, swung a despairing face toward us. ‘If only I could touch him,’ she gasped.” Two thousand years earlier, a woman said of Jesus: “If I only touch his cloak, I will be made well.”

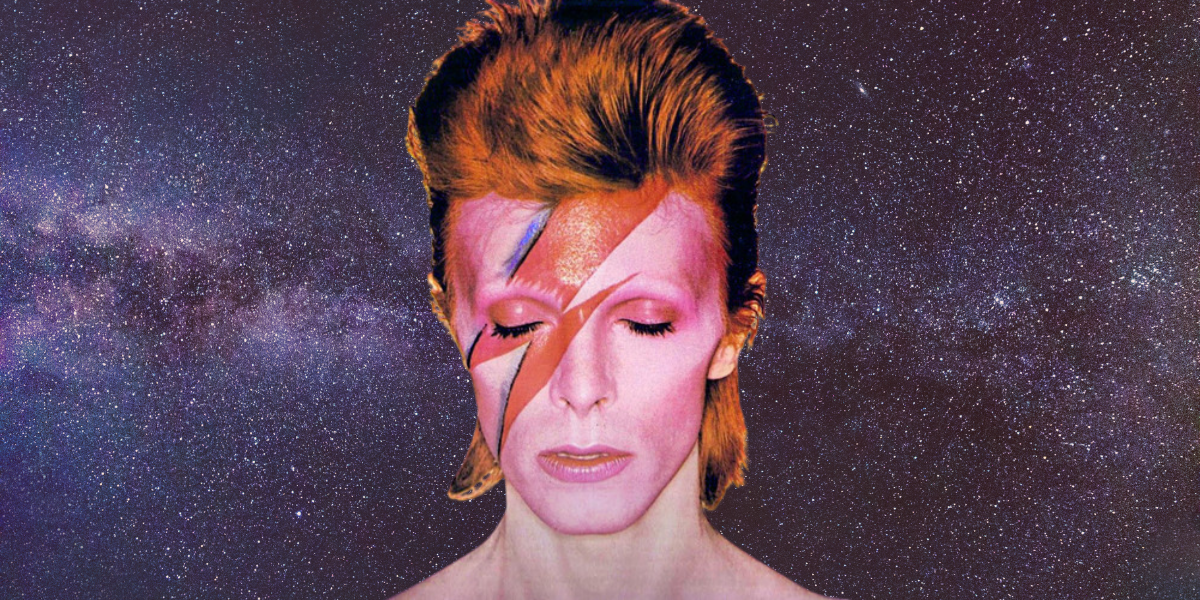

Ziggy Stardust, Bowie’s most famous creation, emerged in 1972. The process took the best part of a year. By the time Hunky Dory was released in December 1971, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars—the album ostensibly telling his story—was mostly recorded. The vision, however, was as crucial as the sound, and the vision was as yet inchoate, embryonic. Bowie had at least cut his hair: those swishing locks had been chopped by the end of that year, and a leaner look took shape.

There followed a curious few months, during which Bowie was supposed to be promoting Hunky Dory; but that album already belonged to a different world. Its opening track, “Changes,” was released as a single in January 1972, and the disc jockey Tony Blackburn named it Record of the Week on his BBC Radio 1 show, ensuring much airplay. It failed to chart, prolonging the streak of duds.

Whatever was driving Bowie hit the accelerator around then. January 1972 was pivotal in Bowie’s career—and, by extension, in musical history. It was the month that Bowie, with Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Woody Woodmansey, saw a new film, A Clockwork Orange. It was directed by Stanley Kubrick, whose previous film had been 2001: A Space Odyssey. Just as its predecessor lodged itself into Bowie’s imagination, so this latest work inspired him visually: the extraordinary outfits worn by the droogs, the film’s gang of stylized thugs, led to the clothes that would eventually adorn Bowie and his bandmates.

Bowie dyed his hair red. Angie Bowie called it “the single most reverberant fashion statement of the seventies.”

It was also the month that a photographer named Brian Ward invited a vibrantly attired Bowie to Heddon Street in London and took his picture under the sign of a furrier and inside a telephone box—the images would appear on the front and back of Bowie’s next album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. It was also the month that Bowie told Melody Maker, “I’m gay and always have been.” And it was the month that Bowie and the band first performed in their new clobber. The musicians were not yet called the Spiders from Mars, but that is what they now effectively were.

February 1972 was pretty important too. Dennis Katz, the head of A&R at Bowie’s record label, RCA Records, was unconvinced that any of the songs recorded so far for the new album would be a hit. So he asked him to write one, and he did; it was called “Starman.” Then Bowie and the band made their first television appearance on the BBC program The Old Grey Whistle Test. Then, at a pub called the Toby Jug in the London suburb of Tolworth, the Ziggy Stardust tour officially began.

Bowie dyed his hair red. Angie Bowie called it “the single most reverberant fashion statement of the seventies.” She wrote: “The new hairstyle triggered new experiments with make-up, and greater interest in clothes, and it wasn’t long at all before young David Jones had transformed himself into a figure that was pure, one-hundred-percent, head-to-toe Ziggy: a lithe, redheaded, face-painted, very revealingly and very originally clothed polysexual stardust alien.”

Then, late in April, it was time to release that song, “Starman.” It was at once familiar and strange, like “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” gone sci-fi, and it changed everything. The reviews were not so much glowing as incandescent; queues for concerts, hitherto often modest, now stretched around the block.

On June 6, 1972, the album arrived. Before you heard the record, you saw the cover. Soggy cardboard boxes, a sack of rubbish, a forgotten and rainswept street whose dankness seeps into your nostrils: behold, right there, your Messiah. This is how a classical nativity scene might look updated for the 1970s: mundanity and detritus glorified by a mere presence.

The title—The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars—suggests a coherent narrative.Yet the album provides none. What we have instead are images, snapshots, memories. It is like a scrapbook that has been compiled haphazardly, the odd vivid photograph pasted among apparently irrelevant cuttings. It represents an amalgamation and a culmination of much that had led him here. The record is perhaps his most famous, but try listening to it in the knowledge of all the spiritual adventurism that has gone before, and it sounds new again. And a fresh possibility presents itself: that it is even more to do with Jesus Christ than its allusions to messiahs might imply.

That Christ bit is really a matter of belief: it is essentially a Greek translation of a Hebrew word, Messiah. In Judaism, the Messiah is the awaited saviour; this figure is sent by God, but is not God. Christianity considers Jesus to be both Christ and God. And by the time the album was released, attempts had begun to recon-cile Jesus Christ—that figure of childhood and the Church and the establishment—with popular culture.

There was the Jesus People movement, a blend of the hippie and the holy, which began in California in the late 1960s. By 1971, Time magazine was proclaiming on its cover “The Jesus Revolution.” That year also saw the first staging of a new musical, Godspell, which told the story of Jesus in Broadwayish pop.

The song tells of a heavenly figure with a message of liberation for humankind.

And there was a more British effort: the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, written by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. It is unclear whether Bowie saw it—he typically loathed mainstream musical theatre—but he was certainly aware of it because the first woman cast as Mary Magdalene in the London production was Dana Gillespie, who had been a close friend since 1964. She also lent her voice to a song on the Ziggy Stardust album. Jesus Christ Superstar had started life as a concept album, released in 1970; among its musical contributors was Lesley Duncan, another of Bowie’s long-term associates, and the writer of “Love Song,” covered by Bowie in 1969.

British readers of a certain age may also be intrigued by a story involving Floella Benjamin: before becoming a baroness and a beloved presenter of children’s television, she performed in Jesus Christ Superstar; one night during the run, she attended a party at Bowie’s house, and rebuffed his attempts to seduce her.

Jesus Christ Superstar used rock to tell the story of Jesus. One could say the Ziggy Stardust album used Jesus to tell the story of rock. But the distinction may not be quite so neat, because the record is infused by Jesus, Christian imagery and matters of God to an extent that goes beyond easy symbolism.

The first song, “Five Years,” comes into vision slowly; then a blast of light from piano and guitar, and Bowie tells us where we are: a market square. People are in shock—in five years, the world will end. The market square may be just a market square, but for one versed in Nietzsche, there is another connotation: in his most famous parable, a market square is where the death of God is declared. And when Bowie next performed in Aylesbury as Ziggy, he wanted the concert to be shown on a big screen in the town’s market square, thereby offering his own proclamation to those assembled. There are scenes of psychic disarray—one involves a policeman, a priest and a “queer”—and the song ends with Bowie’s abandoned, desolate howl, yelling the news repeatedly as if its import is yet to register.

“Five Years” bleeds into “Soul Love.” Visions and concepts from Christianity abound. There is a priest; there is the Word, a term used in Christianity to refer to Christ and to Holy Scripture; there is God, whom the priest calls love; there is a baby and a cross, bookending the life of Christ. Then, once the song has ascended to its chorus, there is a dove, ablaze. Remember that window in that church in Bromley, in whose heavens were the dove and the flame: together, they are a symbol used commonly to depict the Holy Spirit.

The song is also an early exploration of love as a spiritual force. In the song, love is as intimate as a boy and a girl talking, as moving as a woman grieving for her son, as transformative as the life of Christ. The work of love, and the question of what happens when love is absent or defiled, became a central preoccupation.

The next song, “Moonage Daydream,” is mostly intergalactic passion and knowing sci-fi schlock, a Roy Lichtenstein comic-book painting made musical. Yet even here there is a church: whether it’s of “man love” or of “man, love” is up to the listener, but one way or another, it’s holy.

Then a driving acoustic guitar opens “Starman.” The song tells of a heavenly figure with a message of liberation for humankind. There is an echo of those first transcendent experiences of rock and roll for the young David and his cousin, Bowie’s phrasing of “let the children” evoking Jesus’s words: “Let the little children come to me, and do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of heaven belongs.”

What stays in the memory is how the song swoops and soars; but, as with the similarly celestial “Space Oddity” and “Life on Mars?,” it begins on the ground, this time with the narrator at home, listening to the radio. It is a play between the domestic and the cosmic: the verses have an earthy churn to them, before the chorus shoots high and weightless. This is more than mere technique, more than an effective use of contrast—it is an example of a recurring motif, a kind of verticality, an upness and downness. Bowie may be associated in the public mind with songs about space and extraterrestrials, but these are songs about living on earth and striving for the heavens. As he told MTV in 1997 when asked about the aliens in his songs: “For me it only represented spiritual search.”

The final words on the album are Ziggy’s own. “If only I could touch him,” said the girl at the Bill Haley concert. “Give me your hands,” says Ziggy.

Side one of the album finishes with its first unremarkable song, “It Ain’t Easy.” It is a somewhat hoary number by an American named Ron Davies, who released it in 1970. Its inclusion on the album has long been a cause of bafflement among Bowie fans, not least as it was originally recorded for Hunky Dory. But the original radiates a kind of old-time religion; and while the music of Bowie’s version lacks some of that spirit, the words still carry it.

The imagery of the song chimes with some of Bowie’s deepest spiritual preoccupations. A mountain is ascended and the sea is surveyed.There is more ascending and descending between realms, with talk of getting to heaven and going down. And consciously or otherwise, there is another echo of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, as Nietzsche has Zarathustra, high on a mountain, deciding to impart his wisdom to humanity: “I must go down—as men, to whom I want to descend, call it.”

The second side of the album deals more with the mythology of rock and roll itself: performances, audiences, pretences; sex, death, salvation. It is here we find the song “Ziggy Stardust.”

The narrator is a bandmate—a disciple, maybe—recalling his frontman, his leader. Ziggy, we are told, was The Nazz. “The Nazz” is the name of a remarkable work of performance poetry by “Lord” Richard Buckley, who was a major influence on the Beat Generation so admired by the adolescent David Jones. In the poem, whose storytelling style and use of the word “cat” are aped in the song, the Nazz is Jesus of Nazareth. The song describes Ziggy as the confluence of the leper—the great biblical outcast—and the Messiah. Consider this from the Babylonian Talmud, a collection of ancient Jewish writings: “What is [the Messiah’s] name?… The Rabbis said: ‘His name is “the leper scholar.”’’ The song ends with Ziggy being killed, slain by those he came to save.

The final words on the album are Ziggy’s own. “If only I could touch him,” said the girl at the Bill Haley concert. “Give me your hands,” says Ziggy.

__________________________________

Excerpted from David Bowie and the Search for Life, Death and God by Peter Ormerod, run with permission of the author, courtesy of Bloomsbury Continuum, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. © Peter Ormerod, 2026.

Peter Ormerod

Peter Ormerod is a journalist and writer who has written extensively about culture and faith for the Guardian. Peter is also an arts editor for NationalWorld. He has a lifelong fascination with religion, having been raised in a clergy family.