The Challenge of Fictionalizing Sexual Assault

Alena Dillon on Writing About USA Gymnastics

During the harrowing days of the Larry Nassar trials, I was finishing a rewrite of Mercy House—a novel about a nun and survivor of rape who operates a women’s shelter. In many ways, the lives of religious sisters and gymnasts couldn’t be more dissimilar: senior citizens versus teenagers, habits versus leotards, prayer versus acrobatics. But in one particular way, they were different notes in the same song, the #MeToo anthem we began to hear as it played across Hollywood. The Catholic Church, USA Gymnastics, and Hollywood were all biospheres that sheltered abusers, enabling clergy, coaches, and producers to rise to power. They were admired and unquestioned gatekeepers who held their subjects’ life’s work and wellbeing captive without checks and balances. They demanded peak performance as well as silence, deference, and surrender.

The Nassar trial was followed closely by the Winter Olympics, and I reproached myself for tuning in to The Games every couple of years without considering the lives of the elite behind the spectacle. Even if they were never sexually violated, their childhoods were defined by diets, training, discipline, and sacrifices. What was it like for these athletes, their siblings, and parents? Was it unethical to demand each season that they go faster, higher, further? Had we all acquiesced, as audience members, to a sports-centered Hunger Games?

I began researching the lives of gymnastic athletes, and when I surfaced from learning all I could, I began to write what would be The Happiest Girl in the World. But I was reluctant to spend time in sexually violent scenes—to linger, observe, feel, and engage. Even without being gratuitous, in order to curate a few details, I’d have to imagine them all. I wanted to avoid alienating the same reader demographic that, perhaps, had turned away from similar material in Mercy House; I also did not want to cast graphic subject matter as my so-called “brand.” For these reasons, I dedicated a year to writing a gymnastics book that skirted the issue of sexual assault.

Then, later in the process, a peer reviewer gave it to me straight: steering a book about an Olympic gymnast away from the Nassars and Gedderts of their world would be like writing a book set on September 11 without acknowledging the attacks on the towers. Intentionally omitting the topic was, if not downright cowardly, blanching and inaccurate, not to mention a disservice, since readers in our culture could benefit from confronting this material while maintaining the distance of fiction.

Still, taking on such sensitive, heavy, and important material felt like an overwhelming responsibility. In my uncertainty, I returned to research. Memoirs, podcasts, documentaries, news articles, and primary documents helped to crystallize the mechanisms that supported abuse in the particular realm of gymnastics: training camps that were isolated and kept off-grid without phone service or internet access; explicit instructions for athletes to contact the team doctor rather than personal coaches in the middle of the night; punishing individuality and complaints by withholding praise, public shaming, and denying access to training or advancement; incentivizing submission by rewarding those who endured pain silently and obediently; and a selection process that wasn’t strictly quantitative, but subject to the personal preferences of officials whose favor gymnasts wanted to keep.

Then of course, there were the predatory behaviors of the abuser: a friendly and nonthreatening demeanor; establishing a false sense of trust through gifts, food, goodwill, and verbal encouragement; positioning himself physically to block the view of anyone else in the room; sending injured girls back into training so officials came to consider him an indispensable asset; and selling himself as an expert in so-called “techniques” that were, in fact, sexual assault. The rules of a world almost dystopian in its peril fell into place, and I felt compelled to write into that setting—and to share it.

Sometimes, the properties of fiction allow us the freedom to strike closer to the truth.Then came the characters. Some names reflect those of real gymnasts (Gabby Douglas, Aly Raisman, and Simone Biles, for instance) while other characters who very closely resemble real people (Larry Nassar, Bela Karolyi, Marta Karolyi, etc.), are kept fictional with appropriately fictional names. There were a few reasons for that. I incorporated true names of those whose performance and bravery deserve to be lauded; those gymnasts come up only in passing, but as they are historical figures, to brush out their real presence, especially in the ways they spoke out against their organization, felt like a form of silencing.

The names of those resembling perpetrators have been changed, which might seem like self-preservation, and perhaps it is, but only partly. Those characters truly have been fictionalized, and herein lies fiction’s strength. Because I didn’t bear the burden of proof, which often blocks the course of justice, I could read reports, allegations, and firsthand accounts, and believe them, whether or not they were verified by hard facts. I could learn about the behaviors of a few coaches and combine them, or hear accounts from multiple families and assemble them from one encompassing picture into something more accessible. I could make reasonable leaps. Sometimes, the properties of fiction allow us the freedom to strike closer to the truth.

Characters with real names and those inspired by real individuals remain on the periphery of my novel. The ones we follow are of my imagination, and the protagonist isn’t a direct survivor of abuse. (For that, I recommend the nonfiction books What is a Girl Worth by Rachael Denhollander or The Girls by Abigail Pesta.) My characters mainly explore questions that remained dimmed by the spotlight of the case. I wondered how much teammates adjacent to the abuse might have known, why parents didn’t make reports or let their reports be cast aside, and how these people coped (or didn’t) with guilt. The answer was different for each of my characters based on what motivated their silence, as well as their fears, strengths, weaknesses, habits, passions, and ambitions. Their choices weren’t the right ones, but in living alongside them, in experiencing the high stakes of their financial, physical, mental, and emotional investment, they were understandable ones.

What remains unacceptable are the ways in which institutions are designed to capitalize on vulnerable populations no matter the cost, and we can only recognize these broken systems when we analyze their scaffolding. There are many ways we can study these cases, and fiction is one of them. Once we’ve trained ourselves to flag dangerous ecosystems, we can—and must—begin the process of dismantling them.

__________________________________

The Happiest Girl in the World by Alena Dillon is available via William Morrow.

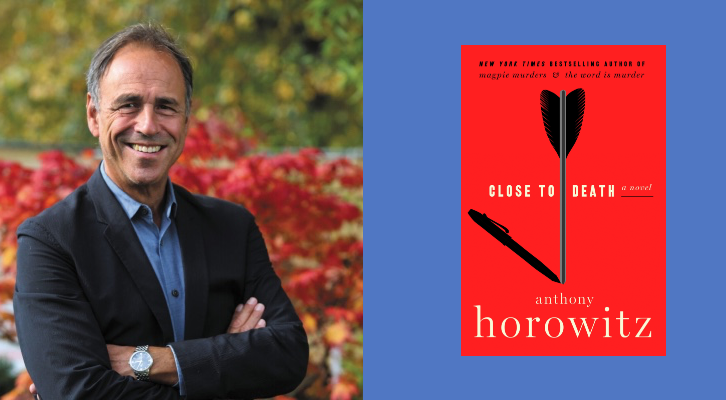

Previous Article

Steve Ballinger on Removing the Remains of War, Nearly 80Years On