The Challenge of Capturing the Complexity of IVF Mix-Ups in Fiction

Genevieve Gannon Considers the High Emotional Stakes of Reproductive Medicine and Family Law

The city where I grew up has a reputation for being cold, except for during a few weeks in summer when the eucalyptus leaves curl on their branches and the dry Australian air becomes so hot it’s dangerous. It was during one of these stretches of scorching heat in the early days of 2016 that I sat bent over my laptop, trying to finish my third novel. My father had died on Christmas Eve a few weeks earlier (it falls in summer in Australia) and I was at my mother’s house in a numb and emotionally blank state.

Writing had become more compulsive than usual. Filling pages felt like it was the only thing propelling me through the days. This book would be my third manuscript for HarperCollins Australia and I was desperate for it to be considered for a print deal. My previous two novels had been published as digital-only editions, and while that had been exciting, I wanted to prove I could write something worthy of the bookstores I loved to visit. I typed deep into the night, producing thousands upon thousands of words each day.

It had been a hard summer and my story about a jeweler whose designs are ripped-off by a big fashion chain was providing much-needed escapism. But after The First Year was quietly released as a digital-only book a year later, I decided I needed to take a break from trying to be an author. I’d moved to a new city, away from my family and friends, and the feelings I’d been writing to escape were starting to catch up with me. I’d been tinkering with an idea for a new book set in the 1930s, but it wasn’t really working, so I decided to stop trying. I focused on my job as an investigative reporter, wrote magazine stories about politicians and missing children, and tried to make friends.

Then one day I was looking into a story about in vitro fertilization when I came across one of the most surprising and shocking news reports I’d ever read. It was about an American couple who had been ordered give up their four-month-old son because, even though the wife had given birth to him, expecting to raise him, a court said he wasn’t theirs.

It took me several reads of the old Washington Post article to get my head around what had happened. The cause was an error in an IVF lab. An embryo had been placed in the wrong woman and when the mistake was made known, the baby’s biological parents declared they wanted custody of the son they had not yet laid eyes on. It was unfathomable. I had trouble believing that such an error could occur, but when I hunted through other press clippings, I discovered it had happened multiple times. In Tokyo. San Francisco. Rome. Leeds. Singapore. It was rare, but it happened. There were no recent cases, and none in Australia, so it wasn’t a subject I could write about for my magazine. But I couldn’t stop thinking about these mix-ups.

My initial reaction was a strong gut feeling that the birth parents should raise the baby they had already bonded with and the court that said otherwise was wrong. I’d find myself at night watching interviews with couples who had been caught up in mix-ups. I was surprised by the different decisions that courts made around the world and horrified by the various details. One single mother found out her son was not “hers” when he was nearly one year old. I could not shake the image of what it would be like to have someone tell you your baby doesn’t “belong” to you.

I started reading beyond the news, hunting through court databases and pulling rulings by judges. I paid fees to join specialized legal databases so I could learn more. I found further details on the first case I had read and learned why the judge gave custody to the biological parents. His reasoning was persuasive. I put myself in the shoes of a woman who has been undergoing the arduous process of IVF for years, who has not been able to fall pregnant, but learns her embryo was implanted in another woman, and that the baby she longs for lives with her.

In an age where one in six couples go through IVF, it seemed important to explore these thoughts that had been playing on my mind. I started to write the story of two couples who, through no fault of their own, find themselves caught in a battle over one baby.

I came to realize the point of writing a novel that explores these mix-ups isn’t the resolution, but everything the characters go through before and after the judgment is made.

Friends who had been through IVF successfully shared hitherto secret details. I devoured every book, blog, and podcast I could get my hands on. On a bus driving through the red center of Australia, I spoke to a woman who had undergone several IVF rounds unsuccessfully and listened to her describe the stinging heartache of giving up.

As I neared the point in the story where I was going to have to step into the judge’s shoes, I began to retreat from the task of putting an answer down on the page. When two mothers both love and have a tangible tie to a baby, how do you choose who gets custody? One example, from 1999, attempted to allow one couple visitation rights, but the arrangement broke down and the court had to make a new ruling that was definitive.

I have no expertise in reproductive medicine or family law, and though I spoke to professionals from both fields the fact there had never been a birth from a mix-up in Australia meant they weren’t able to give me a clear answer on how it might play out. I studied the overseas cases to inform the outcome in the book. The problem was that nobody agreed.

In a British case a judge ruled a husband and wife were the legal parents of twins who were a different race to them, and the man whose sperm had accidentally been used to create their embryo was simply an unwitting donor. This completely dismissed the father’s genetic and cultural connection, which is the opposite to what happened in the first case I described.

Friends I discussed the stories with had passionate opinions that didn’t help me resolve the question. One, a single doctor, was outraged by the suggestion the baby would grow up with people he had no blood ties to while his genetic parents were alive and loved him. A journalist friend and mother-of-two fretted over the damage caused by removing a baby from the parents it had bonded with. Being a parent is so much more than genes, she argued.

Several times I considered abandoning the project, but I couldn’t stop thinking about my characters. It was a story that was important to share and to finish. My couples―Grace and Dan, and Nick and Priya―may have been fictional, but they represented real people who had gone through real hell.

I came to realize the point of writing a novel that explores these mix-ups isn’t the resolution, but everything the characters go through before and after the judgment is made. The courts in New York and Rome, San Francisco and Leeds had done the hard job of making a ruling because it was legally and practically necessary, and those findings had been reported in the press. But the articles didn’t tell the full story. The point of exploring these mix-ups in fiction was to go beyond those black and white columns and consider the sadness and conflict and courage and moments of strength that happen in private. Not to reduce the errors down to a single answer, neatly contained, like a pearl of truth, but to break these mistakes open and lay bare all the questions they raise.

__________________________________________________________

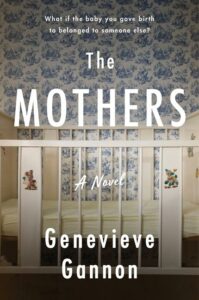

Genevieve Gannon’s The Mothers is available now via William Morrow.

Genevieve Gannon

Genevieve Gannon is an award-winning Sydney-based journalist and the author of four novels. She is presently a staff writer for Australia’s biggest women’s magazine, the Australian Women’s Weekly, where she covers everything from cold-case murders and cults to celebrities and sports stars. Her journalism has appeared in most of Australia’s major newspapers, and she has recently won the Mumbrella Publish Award for Journalist of the Year.