The Chairman Had No Rhythm: What It Meant to Dance with Mao Zedong

Vanessa Hua Follows Echoes of History Around the Dance Floor

On the first day of social dance—one of the most popular classes at Stanford University—I nervously stood in a circle with the other students in the airy gymnasium.

Until then, the sum total of my dance moves consisted of the box-step waltz I learned in middle school cotillion, along with the Hammer Dance, Kid N Play, and the grapevine that I’d bust out at parties. I knew nothing about swing, waltz, polka, tango, and the other dances we’d learn that quarter.

I’m not sure why social dancing remains in high demand on campus, but back in the early 1990s, a half century after swing became king, the classic moves had resurfaced in pop culture. In each class, we paired off with a random partner: my right hand clasping his, hand on his shoulder, his at the small of my back. I waited in hushed expectation before the opening bars began—say, the raucous clatter of drums and brassy horns that usher in Benny Goodman’s “Sing, Sing, Sing” or the playful swelling at the beginning of Johan Strauss’ “Blue Danube”—signaling us to launch into our steps.

In the years after graduation, I dusted off the dance moves at weddings but wouldn’t have pondered them deeply again if not for a beguiling black-and-white photo: Chairman Mao, surrounded by giggling young women. Their hair, schoolgirl-bobbed and tucked behind their ears; their hands touching his shoulder, his arm, and his lap.

In their fitted blouses, they could have been bobby soxers at a soda shop but for the formidable presence of this peasant-turned-revolutionary, cigarette in one hand, the other clasped by an acolyte in plaid.

What was it like for a peasant to get swept into the patriotism of those times and to sleep with a man she’d been raised to worship as a god?

It turned out that Mao was a fan of ballroom dancing—and of young women. Even as he called for an overthrow of the old ways and old thinking, even as peasants and factory workers were told to “eat bitterness” as they toiled, elite dance troupes partnered with him in the ballroom and the bedroom.

When I looked for more information about the dancers, I couldn’t find much. In The Private Life of Chairman Mao, his personal physician, Li Zhisui opines: “To have been rescued by the Party was already sufficient good luck for such young women. To be called to the Chairman was the greatest experience of their lives. For most Chinese, a mere glimpse of Mao standing impassively atop Tiananmen was a coveted opportunity, the most uplifting, exciting, exhilarating experience they would know… Imagine, then, what it meant for a young girl to be called into Mao’s chambers to serve his pleasure!”

I suspected—I knew—the relationships had to be more complicated—especially for those who he kept on as his “confidential clerks.” Take, for example, Zhang Yufeng, who was 18 years old when she met the Chairman at a dance party in the early 1960s—in the liminal years between girl and woman, and so young by comparison to Mao, then in his late sixties.

In time, she would handle and read aloud the reams of documents that the Chairman commented upon daily. Toward the end of his life, when she was in her early 30s, as his speech became garbled by illness, she served an essential role, interpreting what he said.

What was it like for a peasant to get swept into the patriotism of those times and to sleep with a man she’d been raised to worship as a god? The gap in age, in power disturbed and intrigued me in equal measure, and inspired me to write my forthcoming novel, Forbidden City.

In my imagination, I could walk in their footsteps—or rather, their dance steps. I remembered my right hand clasping my partner’s in class, hand on his shoulder, his at the small of my back. Remembered waiting in hushed expectation before the opening bars began, signaling us to launch into our steps, back and forth and side to side. By the end of each session, I was panting, sweaty and exhilarated by the gallop of the polka, the whirling waltzes, the sexy scissor kicks of the tango, and pretzel flash of West Coast Swing.

For Mao’s dancers, what kind of darkness followed that lightness on the dance floor? The notion of consent never would have entered the conversation, in China or elsewhere at that time. The shaming and subsequent reframing of Monica Lewinsky, and the reckoning of the #MeToo movement, were still decades away.

Beyond the sex, though, I wondered what else happened behind closed doors. Nothing I uncovered described the rhythm of their days: how these companions gained his trust and maneuvered the complex politics at Zhongnanhai, the former imperial gardens turned home to Mao and the country’s seat of power.

Then I dug up a droll account of Mao’s rhythm. Or rather, his lack thereof. In 1937, journalist Agnes Smedley, author of Battle Hymn of China, traveled to Yan’an, a dusty rebel stronghold, during China’s civil war. She lived among the Communists in caves that pockmarked the yellow cliffs. With few amusements available—she listed rat catching and gardening as hobbies—she taught square dancing and foxtrot to the military commanders.

Of Mao, she says, “He had no rhythm in his being.”

I picture Mao, then in his early 40s, stepping left instead of right, forward instead of back, off-beat, off-kilter. Smedley wittily described the other officers and how they moved, such as a man who appeared to be “working out a problem in mathematics” and yet another who seemed “the embodiment of rhythm”; he “could hardly contain himself until he was cavorting across the floor.”

What served as escape for me surely must have been a daunting experience for the young dancers who partnered with Mao.

After the Communists took victory, Mao would continue to host dance parties. Officially, ballroom dancing had been deemed bourgeois, but on these occasions he led the girls through the fox-trot, waltz, and tango in a style that his doctor described as a “slow, ponderous walk.”

The contrast between life behind and beyond Zhongnanhai’s high red walls couldn’t have been more stark. In the late 1960s, the Cultural Revolution—launched by Mao to tighten his grip on power—threw the country into turmoil. Even as students violently turned on their teachers and neighbors settled long-held grudges, collective “loyalty dances” flourished. Workers, peasants, and students alike would skip and sing patriotic songs together to demonstrate their love for Mao.

After Mao’s death in 1976, as the country reformed and the Chinese government grip over culture and leisure loosened in the decades that followed, interest in ballroom dancing returned—in China and beyond. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky winning stint on his country’s version of “Dancing with the Stars” in 2006 recently went viral.

During my freshman year, the stresses of problems sets and papers fell away during dance class. As I spun with my partners, everyone and everything blurred around me.

What served as escape for me surely must have been a daunting experience for the young dancers who partnered with Mao. Judged, assessed, prized, and discarded.

Every so often, though, did they also dwell in their bodies fully and freely? Lost in the music, twirling, flying, their heels clicking against the wooden floor.

__________________________________

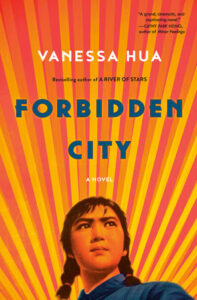

Forbidden City by Vanessa Hua is available via Ballantine Books.

Vanessa Hua

Vanessa Hua is a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and the author of the novel A River of Stars and a story collection, Deceit and Other Possibilities. A National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, she has also received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, and a Steinbeck Fellowship in Creative Writing, as well as awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, among others. She has filed stories from China, Burma, South Korea, and elsewhere, and her work has appeared in publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic. She has taught most recently at the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.