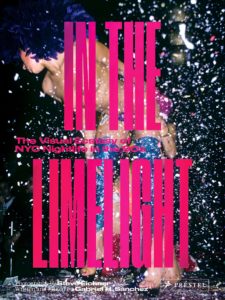

The Center of the Universe? Capturing New York City 90s Nightlife

Gabriel Sanchez on Archiving a Party That Never Ended

New York City nightlife in the early 1990s was a hot and visceral experience. Drenched in throbbing neon while whirling away inside the relentless, pulsating music, a simple passing glance and an open mind could lead to the journey of a lifetime. True freedom was something tangible—even addictive. Freedom from one’s self. Freedom from society’s expectations. Freedom from the politics and anxieties that dwell beyond the club walls. In New York after dark, life was indulged to the heart’s content, and there was plenty to go around.

Bold experiments in music, fashion, art, and sexuality set the tone for decades to come and established a new paradigm of American culture, one that extends well beyond the realms of nightlife and entertainment. Sexuality was celebrated in all of its colorful forms and without judgement. In these clubs, every breed of New Yorker—from candy-eyed ravers to Wall Street suits—intermingled with respect and longing for an unforgettable night.

A night in clubland wasn’t lived vicariously through social media or filtered through an Instagram feed; these nights were experienced raw and unspoiled. Influencers wore their statements in bright and colorful expressions on the dance floor. What went viral were sentiments of peace, love, unity, and respect. Many of the clubs in Manhattan enforced a strict no photography rule, and because of this, the greatest nights were experienced one time and one time only. In 90s clubland, you just had to be there.

In the decade before this scene hit, New York City was a void waiting to be filled by a new generation. The AIDS crisis and its horrendous toll on the city had shuttered most of the adult playgrounds of the day. Mega clubs like Studio 54 had met their demise under Mayor Ed Koch’s crackdown on illicit club activities, while the punk rock ethos of downtown bands like the Ramones and Blondie had slowly sunk into plastic commoditization. In 1987, the death of Andy Warhol marked the end of an artistic era.

That same year, 22-year-old Steve Eichner left his hometown of Long Beach, New York, with the dream of making it big as a music and celebrity photographer. As with most starry-eyed kids who ditch their hometowns for the Big Apple, Eichner was passionate and ready to work. He set up his photography studio at 27th Street and 10th Avenue and soon after landed a gig as a nightlife photographer for an independent magazine. An addictive routine ensued: late nights with camera in hand among the swirl of downtown clubs like Quick, Reins, and Glamorama, followed by early morning hours at the photo lab. Then repeat.

Eichner earned a reputation as a reliable and talented photographer and caught the attention of Gene DiNino, owner of the Roxy nightclub, and was granted access into the venue’s exclusive VIP spaces. Located at 515 West 18th Street, the Roxy was loud and proud, featuring an erotic roller disco and a house drag queen that could be seen soaring above the dance floor on her suspended throne. For Steve Eichner, this was pure visual ecstasy, but the party didn’t end there. Through word of mouth, he soon discovered the thrilling world of illegal raves on the streets of Manhattan known as “outlaw parties,” and the outrageous Club Kids who threw them.

An “outlaw party” was, in essence, the glitter-bombed forefather to the flash mob—imagine a quiet, late-night dining room in a midtown McDonald’s suddenly erupting into a stampede of drag queens, three-eyed trolls, and dancing yellow chickens. From when the first cup of spiked Kool-Aid was poured to the moment the police arrived to dispel the crowd of hundreds that had gathered to party, it was pure adrenaline-fueled ecstasy.

In 1991, Steve Eichner was hired by Peter Gatien, an uncompromising entrepreneur from Quebec whose financial ventures in New York nightlife defined him as the undisputed “King of Clubland.” As house photographer to Gatien’s club empire, Eichner was granted exclusive access to some of the most iconic venues of the era: the Limelight, Tunnel, Palladium, and Club USA. In this new era of clubbing, every detail of the evening—from the neon ambience to the go-go dancing Club Kids—was coordinated to make each paying guest feel as if they were at the center of the universe. The parties would operate like amusement parks for adults and for twenty dollars at the door you were granted an experience like no other on earth.

In the shell of a nineteenth-century deconsecrated Episcopal church at the corner of Sixth Avenue and West 20th Street, the Limelight was the crown jewel of Gatien’s pulsing empire. Under stained glass windows and religious iconography, subcultures thrived and crossbred with one another—everything from Goth and experimental electronica in the upstairs Gregorian room to Club Kid Michael Alig’s notorious Disco 2000 parties hosted in the Library downstairs. There was a room filled entirely with foam and on the Limelight’s main stage, the era’s most buzzed about alternative bands broke new ground during the weekly “Rock ’n’ Roll Church” event. Going to church had never been so much fun.

Further west in the Chelsea neighborhood was Tunnel, situated in an old railway station on 12th Avenue between 27th and 28th Streets. On any given night, the entrance line could stretch a full city block to 11th Avenue. The venue’s long and dark railway design offered plenty of space to stretch out and indulge in any form of sinful activity, while each themed room offered its own unique experience: the Lava Lounge, Victorian libraries, a ball-pit room, and even an S&M dungeon designed as an adult playground for pleasure and excess.

Off Union Square was Palladium, a mega club located in what is today a New York University dormitory on 14th Street between Irving Place and Third Avenue. The building was built in the 1920s as a movie palace and by the sixties was hosting bands like the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead. When Steve Eichner and his camera arrived, the bill featured music icons like Prince and Run DMC, as well as new acts like Naughty By Nature, LL Cool J, and A Tribe Called Quest—solidifying this venue’s reputation as New York’s premiere hip-hop scene.

Of all the spaces that Gatien held dominion over, perhaps the most fantastic representation of ’90s clubland was Club USA. Located in the heart of Times Square in what was once Broadway’s Central Theatre, its interior was designed to blend seamlessly with the barrage of consumerism right outside its doors. Gigantic neon billboards above the dancefloor stood as effigies to the old Times Square, along with porno booths and XXX adverts in every nook of the club. None of this was as shocking as the three-story slide from the upper bar to the ground level that saw club goers zipping down headfirst with their skirts upended. It was here that Eichner managed to document an incredible array of the era’s cultural figures—Joan Rivers, Steven Tyler, Kate Moss, Leonardo DiCaprio, Tupac Shakur, and even Donald Trump. Everyone who was anyone in the ’90s went out of their way to be caught on camera at Club USA.

With little warning, Club USA closed its doors to the public in 1994, after only two years in business. Following a bankruptcy filing by the building’s owner, all of the site’s tenants were unceremoniously evicted. As fast as Club USA had burst onto the scene with its over-the-top antics and ambitious vision, it too had become a casualty to the very thing it’s concept encapsulated—the passing of one New York City era to the next.

For Peter Gatien, the closing of Club USA marked the beginning of the end for Clubland; by the end of the decade, Gatien would be deported to his home country of Canada under charges of tax evasion. Many of the promoters, artists, and Club Kids who helped define the scene had succumbed to the lifestyle’s heavy use of drugs and alcohol; and in 1996, the murder of Club Kid and purported drug dealer Andre Melendez by Michael Alig and his roommate Robert “Freeze” Riggs meant that the party was truly over.

For Steve Eichner, it meant new beginnings. In the years following his clubland escapades, Eichner was hired as a staff photographer for Women’s Wear Daily (WWD) and became a fixture of the New York fashion industry, documenting over forty fashion weeks and attending an incredible twenty-one Met Galas during his tenure. His pictures have since been featured in Vogue, the New York Times, Newsweek, Time, Rolling Stone, People, Vanity Fair, Cosmopolitan, W Magazine, Details, and GQ.

As for his archive of thousands of images made as Gatien’s house photographer, the original slides were placed into a climate-controlled storage in Long Island where they would remain untouched for the next several decades. In 2019, Steve Eichner, along with myself, revisited this enormous trove of photographs and began the process of formally cataloging and archiving the original source material. More than a collection of party photos from the ’90s, what was rediscovered in those crates stand as a testament to the significant impact of New York City nightlife on today’s popular culture.

Each frame is like a snapshot from a fever dream that tingles the senses—the visceral heat of the bodies, the smell of the spilled liquor, the deafening bass. For the people frozen in time within these images—the starry-eyed kids from Long Island, the flamboyant drag queens and Club Kids, the entrepreneurs and the suit-and-ties, the eyes of youth, and the aged wisdom—the party never ended. It’s been raging for decades within binders collecting dust in a Long Beach storage facility. For all those who missed the party or who keep those memories stored away in the backs of their minds, these photographs capture a generation that shared an electric vision of the future and chose to make it their reality.

__________________________________

From In the Limelight: The Visual Ecstasy of NYC Nightlife in the 90s by Gabriel Sanchez. Used with the permission of Prestel Publishing. Copyright © 2020 by Gabriel Sanchez and Steve Eichner.