There was the sound of gunshots going off somewhere in the distance. But there was no reaction to them on the young girl’s face. She was sitting in the back of a flatbed truck, between boxes of cabbage, facing the road. She looked no more than twelve, but in truth, she was fourteen years old.

Sofia was dressed in a threadbare black coat that looked as though it had seen more winters than the girl had been alive. It surely must have been passed on to her. Her hair was tied up on her head with a flowered red kerchief, a pattern that was popular with the peasants.

The truck rumbled quickly down the country roads. It seemed to react to every stone it went over. The cabbages leapt out of their boxes and fell back in. The girl looked rather precariously perched. As though one large bump might launch her right off the back of the truck. But she sat up there stoically.

She was holding a large goose in her arms. The goose remained still, only moving its neck occasionally to get a better look at where they might be going. The girl held on to the goose as though it was her only possession. As though it was the only object she owned, and there was a good chance it was. People were being displaced all over the country because of the war. And they could be found clutching the most random of objects.

Her thin fingers that were gripping the goose were soft and unblemished. How was it that this girl had hands that looked as if they had never worked a single day in their lives?

Although she was dressed like a peasant, and at first glance would easily be mistaken for one, there was something about her pale face that looked refined. It looked as though it could belong only to an upper-class girl from the Capital.

She had grey eyes that were common in Elysia and thin dirty-blond hair that fell in stringy locks from her kerchief. She was not beautiful. In fact, she might have been considered plain. But her expression had a certain conceit and sophistication to it. It was this arrogance the Enemy had been so vocal about in their propaganda. The devilish, corrupt pride of the metropolitan elite, whom they wanted to destroy at all costs. But the most striking thing about her was that she was all alone. Were it not wartime, surely some adult would have been with her. But people had already begun to look away when they came across children who had been separated from everyone they loved. She was like a stray dog people avoided eye contact with. It was not at all good to look into the eyes of a broken animal. It was too much to bear. She was a million miles from anyone who could help her.

*

At the beginning, her mother didn’t believe in the war at all. Or she wasn’t afraid of it. She deliberately made provocative statements about not being afraid. She said war was good because it always created new forms of art. She thought it was particularly good for theatre. There was nothing like seeing a play right after a war.

But then the Enemy had entered the country easily and now occupied the beautiful Capital. It had upended all their lives. And in fact, all the theatres and newspapers and concert halls had been closed, as Elysian art was now illegal. Sofia’s mother was at the very centre of the art world. It could be claimed that Clara Bottom was the Simone de Beauvoir of Elysia. She was the first to write in their language what it is to be a woman. That one is not born but becomes a woman, more or less. And thus, she was on the Enemy’s most wanted list.

The Enemy had come to reclaim the land they had lost in a treaty after the Great War. The Capital had been spared the mass destruction the rest of the country had seen. Of course, the Capital was considered sacrosanct by both sides. Now the citizens of the Capital existed in an uneasy lull in the violence, waiting to see what would happen next, while slowly building an underground resistance. Clara Bottom inserted herself right into the heart of it.

Whose idea was it that all the children should flee the Capital? From the very beginning of the Occupation, parents had asked that their children be allowed to leave to stay with relatives in the countryside. To spare them from what, exactly? the Enemy asked. But they were too afraid to answer. And then the Enemy announced that children could leave the Capital on a special train the following weekend. Sofia’s mother immediately began preparations for Sofia to be on that train.

“I am not a child anymore,” Sofia protested. “I don’t want to be sent away with the children.”

“Don’t be a fool, Sofia. This is an opportunity to escape. The Enemy is letting children leave.”

“You aren’t leaving. I am going to stay here with you. I want to be a war hero too.”

“A war hero! There are no heroes in this war.”

“I am staying for the Uprising.”

“Oh, you are stubborn and ridiculous, Sofia!”

“You want me to leave. You’ve never liked being a mother.

You never wanted me to be born.”

Sofia’s mother was being bossy about what Sofia put in her suitcase. Sofia did not think this was fair. She never liked when her mother told her what to wear or how to act. But now she would be where her mother couldn’t even see her. So why should Sofia care? She was going to stay with some third cousins who lived in a small village. She could not even tell you whether it was a cousin of her mother’s or her father’s.

She asked about her new cousins.

“You’ll be very good for them,” her mother said. “Make sure the children pick up your accent and not the other way around. And read every night. You have to learn to have a rich vocabulary when you are young. Otherwise, it will never seem natural when you use large words later on in life. I know it’s heavy, but I’ve put a large book in your suitcase.”

“Oh, this is awful!” cried Sofia. “I am not a child. You cannot send me away with all the babies. I am needed in the Capital, just as you are!”

“This is your way out, darling. Just be a child for the duration of the train ride.”

Sofia picked up her suitcase. It was heavier than she thought. She opened it again. She saw her large folklore book, Tales from the Forests of Elysia, inside it. She was pleased. “My book!” Sofia announced.

“Look, darling, this is the most important thing I will ever tell you.” She took out the book and opened it. Sofia noticed at once that the book was different. The pages had been taken out and replaced by her mother’s latest manuscript. “You are to deliver this book to the people who are meeting you at the train station. You know how valuable this is. It is my life. It is our lives. I have to get it out of the country.”

“No! You’ve ruined my favourite book.”

“Why must you be so obtuse, child? The fate of the bloody country is on your shoulders, and you’re worried about a handful of fables. You say you want to be a resistance fighter. You have to get this book to people who will get it out of the country. You’re the only one who can do it, Sofia. We have to get the word out to Europe. They have to know that we are like them. They can’t let a civilized society filled with thinkers and artists be razed to the ground. They think we are still backwards and barbaric. They don’t understand that we are nothing like the Enemy. We are like them.”

“You don’t love me. You love your writing first.”

“Of course the book is more important than you. It’s my memoir, yes. But it’s more important than me. It’s the celebration of an Elysian life. What are any of us except expendable during a war? It’s the idea of freedom that has to be saved. It’s a culture that we created. If we can keep that alive, we are all saved. Our individual fates don’t matter. Don’t you think about yourself. Think about the book. It has to make it out of the country.”

“I can’t travel with children. What if the girls from my class are there? No, I cannot get on the same train as them.”

The train station was filled with mothers. Sofia believed that when a train pulled out of the station, all the mothers felt a burden lift from their shoulders. In Sofia’s mind, wartime was the most wonderful time for married women in the city. They all went back to behaving like young girls. Women never actually liked being mothers; they only liked the idea of motherhood beforehand.

Her mother had taken her to the train station to see her off. She was wearing her most fashionable dress. Her mother was usually lazy when it came to anything involving paperwork, so Sofia was surprised she had managed to sign her up for this transport.

It was the only time her mother had been efficient about anything. Of course! Her mother wanted to get rid of her so she could have lovers. This wasn’t about any manuscript, it was about being free of her. With her father safely in America on business, having left the country before the Occupation, her mother wanted to be a single woman. And although Sofia missed her father occasionally, her mother never seemed to. Free of a husband, she had now traded her daughter for currency on the dating market.

Sofia was surprised by the number of children on the train platform.

As the mothers began to recede, she saw she was in an enormous crowd of children. It seemed possible that at least half of them would get lost. It was hard to keep your wits about you. The children had their stops written on tags around their necks. If they were to miss their stop, they would be lost forever.

There was no one to take their hands. So they found themselves deliberately touching others so they would not feel alone. They stepped carefully on the heels of the children in front of them as they boarded; they held on to another child’s scarf. You wanted to hang on to somebody.

Sofia did not like having the burden of carrying the book with her mother’s manuscript in her suitcase. It meant she had to worry about the book on top of herself. She felt all the other children had been told to look out, above all things, for themselves. But she knew she was supposed to prioritize the book. She couldn’t think properly. It was as though the book inside the suitcase were speaking loudly over all her thoughts. In prioritizing the book, her mother was prioritizing herself over Sofia. Sofia had a sudden urge to open the window of the train and shove the suitcase out. And be free of it.

__________________________________

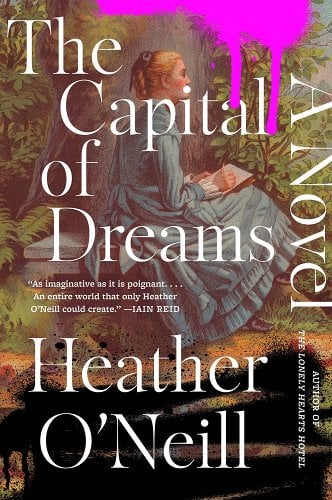

From The Capital of Dreams by Heather O’Neill. Used with permission of Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2025 by Heather O’Neill.