My mother had placed a tape recorder in every room of our apartment. They were cheap and easy to find at secondhand stores, as were the tapes. When she brought them home, she tried to hide them by placing one piece of folded white paper over each device like a little tent. Each room, with its white paper tent. She had started buying them weeks before that phone conversation with Aunt Minn, and when we were in a room together, she would casually drift over to the tent and sneak a finger underneath to find a button and press Record. Then she’d make breakfast, or play cards with me, or we’d watch Toy Story 2, or I’d do my homework. I understood implicitly that they were not to be discussed, that I was to think the little white tent was an actual cover, and her pressing of the button invisible to me. I suppose I liked the idea of a shared secret, even if she did not know I shared it. In fact, had she looked carefully, my mother might’ve seen a few more white tents on appliances in my bedroom as a tribute: a white piece of paper over the clock radio, a white piece of paper folded over a broken camera. This field of tents, this camping ground of our home. In the other rooms, we would play our games and eat our meals, and I grew used to the rubbery click of a cassette running out, a button upending as the closing point of most activities. At some point, while I was at school, or asleep, she must’ve flipped the tapes, but I never saw that part. They were always prepped and ready to go. When the volunteer mothers from my school were packing up the apartment and going through her and my things, they mentioned nothing to Aunt Minn about any bag full of labeled cassettes, any grand plan documentary, which was not a surprise; Mom just wasn’t generally that organized. I never ended up asking her about them, but it didn’t seem like a long-term project. More like she wanted some proof in case I did something bad. And, as I think of it now, probably keeping an ear on herself, too.

Before those volunteer mothers arrived, when I was gathering a few of my own things to take with me before I went to live with my aunt and uncle in their home in Burbank, California, I lifted each little tent like the boxtop of a present and took the tape recorders, slid each one into my purple drawstring bag along with a stuffed brown bunny I didn’t really care about and some word search books in which I had already found all the words. I had no idea what to bring. The scrim of meaning had floated off of everything.

I suppose I liked the idea of a shared secret, even if she did not know I shared it.I brought the recorders with me on the train for two days, and then into the car and up the walkway to my new home, on the quiet street of well-tended lawns and a bright blue tire swing across the road hanging from the gnarled branch of an oak tree. Supposedly, when I rang the doorbell, and my aunt answered, holding a tiny fretting brand-new infant in her arms, hair frizzed, face etched, I pointed to myself and said, “Francie.” “It was the most heartbreaking thing in the world,” she told me years later, pressing my hand, “as if we were acquaintances at a party.”

That morning, she hugged and kissed me as she led me up the stairs. My room was to be at the top of the staircase, with windows that looked out upon the street, and a faint odor of yoga mats. It had been previously used as an exercise room and an office, and so all the equipment had been shoved to one side, shrouded by a few old green sheets, and by the closet they’d set up a futon draped in a too-large comforter and a nightstand made of a packing box covered by a towel. She had no spare reading lamp, so she’d placed an industrial flashlight on the towel in case I liked to read at night.

“I’m so sorry,” she said, bouncing the baby, who was wrapped in a blanket. “We’ll get this into shape. We just have been so consumed.”

“I like the flashlight,” I said.

“We’ll go online. We’ll order whatever you like.”

“What is the baby’s name?” I asked, still standing in the doorframe.

She blushed. Her eyes seemed to have constant water in them, a vivid hydrated health. She looked nothing like my mother. “Vicky,” she said. “Your cousin Vicky. Or, maybe—your sister?”

“Cousin is good,” I said, holding out a finger, which the baby grabbed.

Months later, after extensive shopping, once I was settled in my new room, with its yellow skirt on the bed, and cloud- painted lamp, and painting of rainbows perched on clouds on the wall, and art table, and cardboard dollhouse, on an after- noon when I had nothing to do, I emptied the purple drawstring bag of its devices, inserted a tape, and pressed Play on the one from the Bathroom, and then the Kitchen. I had been missing my mother very much, but it turned out I couldn’t stand listening. Hearing my squeaky voice, hearing hers. The cracking of eggs for breakfast, her laughing as she brushed her teeth and sang me a song about spitting. The dim sounds of Go Fish. The conversation from the Living Room recorder between us all was the only one I could listen to in full, because it was the last I had, and the easiest to rewind to, and didn’t cause the same kind of ache.

*

I don’t know whether there is a lot of documentation on psychotic people and psychic people and if they have any overlap. I’m guessing no. Most people in the grip of psychosis are not usually considered trusted custodians of the future. The man at the bus stop warning us all about the end of the world has been there since its beginning, since there were bus stops to stand by, or their bygone equivalents, like the horse trading station. There he was, by a pile of hay, yelling of brimstone, and no one paid him much mind then either.

But it turned out that my mother was right about the bug. She was several days too early, and mine had not been crawl- ing, but there would end up being a bug in me after all, just a few days after she checked into the hospital, my fated bug, a butterfly I’d found at the babysitter’s apartment, floating like a red and gold leaf so prettily on the top of a tall glass of water. I did not have any other way to hold on to it, and I could not possibly leave it in the babysitter’s apartment, and the only container handy was myself. Time was short. I drank it down because I had to.

__________________________________

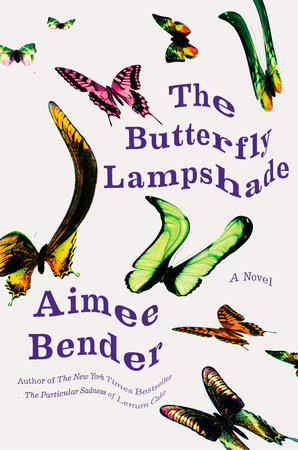

From the book The Butterfly Lampshade by Aimee Bender, published by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Aimee Bender.