The Bounce Song That Launched a Thousand Bounce Songs

Big Freedia Remembers MC T. Tucker's "Where Dey At?"

The last semester of eighth grade, right before my thirteenth birthday, my life changed for two reasons. One, the first Bounce song came out. And two? Well, we’ll get to that.

Dances were the only part of school I took any pleasure in. It was January 1992 and I was getting ready for the first dance of the new year. That Saturday night, I took special care getting ready, especially because my new crush, Marc, was going to be there. My white polo shirt matched my new white Reebok Classics. I dabbed some activator gel on my newly buzzed flattop. And then I caught a glimpse of my stomach squeezed into my new blue jeans. My waist was a size 42. Damn it! I was a big, fat sissy. No way around it.

“You look beautiful, honey,” Momma said as she came up behind me.

“Thanks, Mom,” I replied.

Ms. V grabbed her keys and hollered out to me that we had to hit the road. We hopped into her old Ford Grand Marquis, which me and my sister and Adam called the Blue Lagoon, and she drove me to school.

“You gonna ask Shatoney to dance?”

I tried to tell her, again, “No, Mom, it’s not like that with us.” Seemed liked nearly everybody except my mom and Shatoney herself knew I was gay.

The DJ was getting ready to drop the needle on the record and I was dying to hear it.

I was resentful that I had to hide my gayness at home and felt guilty that the most important person in my life—my mom—would be the last to know. I couldn’t live without her, that much I knew. I wondered if her fear of God was stronger than her love for me. I wanted to tell her so badly right then and there. My mind flashed to the older punks like Sissy Leroy and Shannon. I don’t know how they dealt with all the hate back when they were growing up. Thank God for them because at least I had people who came before me to look up to.

I decided to just spit it out. My palms started to sweat.

“Well, who do you like, baby?” Momma asked.

I imagined Marc’s deep chestnut eyes and his sturdy jawline, and my mouth was suddenly too dry to talk. I could see the school flagpole at the end of the street. This conversation would have to wait.

“No one, Mom, I don’t want to date,” I said.

She stopped the car and patted my arm. “I don’t believe that, but you go on and have a good time,” she said. “See you at eleven.”

“Bye, Momma,” I said. I stepped out of the car and slammed the door harder than I meant to.

I waved to Miss Harrison and Miss Smith as I entered the gym. Multicolored streamers were hanging from the gym ceiling. DJ Peewee had already set up his turntables below the basketball net and a few kids were already on the dance floor shaking to Run-DMC’s “Peter Piper.” I scanned the court for my best friend at school at the time, Antoinette, but she was nowhere in sight. So I walked over to the bleachers to wait for her.

Shatoney ambled in, all dressed up in a short pink skirt and some cute pink sandals to match. I wanted to run the other way but she looked right at me and broke into a shy, wide grin.

“Hi, Freddie!” she mouthed and blew me a kiss.

“Hi.” I waved back. She walked with a dip over to me and leaned on the bleachers. Two boys in my class, Kevin and James, were watching her, their tongues practically on the floor.

She flounced down next to me in a suffocating cloud of White Diamonds perfume.

“You gonna dance with me tonight?” she asked. I felt terrible. She had long dancer’s legs and perfect milk-white teeth, all of which was wasted on Big-Freedia-to-be.

“Yes,” I said, trying to be a sport. Just then, Kevin and James walked over to the DJ. I knew they wouldn’t acknowledge me, but I was desperate to escape Shatoney’s obvious affections. I marched toward them, as if I had something important to tell them.

“Y’all heard that new song by MC T. Tucker and DJ Irv?” Kevin asked Peewee. The DJ held up a vinyl labeled “Where Dey At?” The way Kevin and James squealed piqued my curiosity.

By the early nineties, hip-hop was fast becoming mainstream across the country. Run-DMC, LL Cool J, and the Geto Boys were played on the radio and at house parties. But in proud New Orleans, we had our own sound—more stripped down, bass heavy, the topics more hard-core, like our lives. But this was way too explicit for school dances. Even Peewee knew it had to be cleaned up for a school dance.

The DJ was getting ready to drop the needle on the record and I was dying to hear it. And then, boom! It sounded through the speakers. Like nothing I had ever heard, it was that “Triggerman beat,” which would become the blueprint of nearly every Bounce song. Shatoney was on it. She grabbed my hand and I couldn’t help but follow her onto the floor with everybody else. Kids were waving their hands, shimmying and shaking like I had never seen my classmates do before. Marc was dancing with LaToya and I wanted to cut in, but I knew that wasn’t gonna go over too well.

We must have danced for hours, one hip-hop song after another, until the dreaded slow jam came at the end of the night. Miss Smith turned down the lights. Peewee keyed up “Stay” by Jodeci and before I knew it, Shatoney had grabbed me around the waist and laid her head on my chest. Nothing to do, right, but relax and enjoy it. As we swayed back and forth, I watched Marc and LaToya.

Tonight, let’s start our love again

Tonight, we can be more than just friends,

Don’t you know, the sun it is going down,

Stay for a little while.

The next thing I knew I was hard as a rock. Where did that come from? I tried to pull away, tried to force myself to think of something else, but it was too late. I was aroused and there was nothing I could do. Don’t think Shatoney didn’t notice. This was sending the wrong message to her, but my whole body had responded in a way that totally surprised me.

When the song ended, I started to pry myself loose. “Gotta run, baby,” I said to Shatoney. She looked like she was about to cry, so I stepped back and hugged her. “See you Monday,” I said, feeling like a cad.

It was the song playing at every house party that year, pumping out of every car and boom box.

I walked downstairs and saw Ms. V was out back smoking a cigarette, so I called Addie about that song “Where Dey At?”

“You hear that song by MC T. Tucker?” I asked.

“Yes, bitch! ‘Where Dey At?’” he said. “Where you been?”

“Come over in thirty,” I said. “When my mom leaves, we can go to Peaches,” I added, referring to a local record store. This was the start of me buying all the local rap I could get my hands on.

At Peaches, I bought a copy of the record on cassette with the money I had saved from my allowance. Addie also urged me to get “Putcha Ballys On” and he bought “Pop That Thang.” Both were new tracks by Bust Down, an artist from the Ninth Ward. When we got back to the house, we put “Where Dey At?” on my mom’s phonograph. I couldn’t believe the explicit lyrics. Fuck David Duke, fuck David Duke, I said, I said, I said. I said, Fuck David Duke, fuck David Duke. It was raw. It was explicit—Dog-ass ho better have my money.

We were transfixed because it was so defiant, so wrong. And apparently we weren’t the only ones who thought so. “Where Dey At?” turned out to be a huge moment in Bounce history. It was the song playing at every house party that year, pumping out of every car and boom box.

But what made it different from everything else—and significant—was that it sampled that Showboys beat. The Triggerman beat made its way into numerous New Orleans rap songs after that, and that’s what makes it a Bounce song. I don’t know why we love that beat so much. Maybe because it’s reminiscent of big-band jazz sound and parade traditions. Either way, it would become the defining sound of Bounce music. If it has the Triggerman beat, it’s Bounce!

“Where Dey At?” was such a local sensation that a year later in New Orleans my boy DJ Jimi covered the song. His version was more polished, and in 1992 it landed on the Billboard rap charts, which was huge: New Orleans was starting to make an impact on a genre completely dominated by New York and Los Angeles.

We played “Where Dey At?” for hours that night. When it was time for my mom to come home, I slipped the cassette under my mattress. My momma didn’t have a problem with mainstream hip-hop but the F-bomb and the N-word were off-limits (even if she did say those words herself from time to time). My momma could be a mess of contradictions, and you just had to roll with it and figure out which rule she was running with at the time.

__________________________________

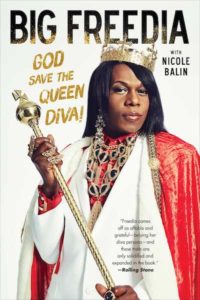

From Big Freedia: God Save the Queen Diva! by Big Freedia with Nicole Balin. Copyright © 2015 by Freddie Ross Jr. Published by Gallery Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Big Freedia

Big Freedia, born Freddie Ross, is a New Orleans hip-hop musician known for bringing "bounce" from the underground music scene to the forefront of the industry. Known for her supreme star power and charismatic charm, Big Freedia has performed alongside such artists as pop duo Matt and Kim, Wiz Khalifa, and Snoop Dogg. Big Freedia's music success is complemented by her television stardom in the reality show Big Freedia: Queen of Bounce, airing on the Fuse network. Big Freedia: God Save the Queen Diva! is her first book.