The Booksellers’ Year in Reading: Part Three

We Asked the Best Readers We Know What Books

Stayed With Them This Year

This is the third and final part of our year-end series wherein we ask booksellers to tell us about the highlights of their year in reading. You can read parts one and two over here.

*

Jeff Waxman, bookseller-at-large

For Christmas last year, my girlfriend got us a membership to the New York Mycological Society and so when the sun rose on January 1st we were stalking about a frozen Central Park with the other mushroom enthusiasts in search of cold fungus. For the next six months, I was absolutely mushroom crazy and it was in the throes of this mania that I latched onto books like Flowers of Mold and The Mushroom at the End of the World, and Fungipedia, even though Flowers of Mold by Ha Seung-Nan and translated by Janet Hong isn’t really about mushrooms at all. Instead, it’s a sinister collection of short stories that really gets into your head—a series of crushed dreams and failed promises and social decay that is at once oppressively real and strangely cold. Which kind of sets the scene for 2019.

Or it would have, but Anna Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World, an exploration of the natural, economic, ecological, and cultural life of the matsutake mushroom, tells a different kind of story. Said to be the first thing to grow in the bomb-blasted ruins of Hiroshima, the matsutake holds an extraordinary place in Japanese life and the logistics around importing this elusive mushroom have far-reaching and extraordinary connections to distant lands and far-flung people. Subtitled On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, the matsutake’s story is expansive and this book is the key to understanding the role that a single commodity can have in a global network, and the hope that we still can have when it seems that everything is coming apart. Of these three books, Fungipedia is the book that comes closest to an actual jaunt with the mycological society. Though Lawrence Millman guides us through mushroom lore more than genetics and taxonomy, he does so with glee, relish, and a warm familiarity gained from a lifetime of expertise and deep knowledge. Both of these were published by the fun guys at Princeton University Press.

I don’t know how I only happened on Ottessa Moshfegh this year, but I am outraged that it took my friends so long to recommend Eileen. I won’t presume to tell you that Moshfegh is very good. She knows it and everyone who has spent any time with me knows that I know it and you probably know it, too. We don’t have to talk about it here. But after I read her first novel, I picked up McGlue, Homesick for Another World, and My Year of Rest and Relaxation in quick and greedy succession, then spent the early months of the year looking for more voices like hers. What I learned is that there are no voices quite like hers, but I did find some that were plenty exciting and one of those was Halle Butler and her novel The New Me.

The creep of economic precarity and labor insecurity into the millennial generation of the upper middle class, the notable absence of men in the lives of women, and a potent strain of social hostility together make this pretty much THE novel to read to understand the women of my generation. Butler doesn’t pretty anything up, not the ambivalence about bullshit jobs or the professional striving or the materialist hunger for lifestyle and unearned satisfaction, and especially not the noxious depression and lingering hope that drive this novel’s action. It’s a story full of private shame made public and almost-guilty admissions, perfect for readers of Helen DeWitt. And in case this doesn’t sound funny, our heroine is even named Millie. The millennial. You can laugh now.

At some point, an enterprising publicist—probably another millennial working a thankless job—had the good sense to send me Shashi Tharoor’s Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India, out now in paperback from Scribe. Originally researched for a speech in favor of reparations to India from Britain, Tharoor laid out a history of the British Empire in India that definitely wasn’t taught when I was in grade school. Before 1600, India was the seat of some of the greatest and most technologically advanced societies in the world. Fully a quarter of the global economy—fabrics, metals, and trade—was Indian. But then the British East India Company systematically squeezed India, turning one of the richest countries in the world into one of England’s poorest colonies. This book details how the theft of a nation’s wealth by a private corporation masquerading as a government created Great Britain as we know it, but Tharoor also offers a crucial understanding of colonial economics and the origin of wealth, and a window into just what Facebook, Google, and Amazon are doing to us all right now.

After nearly 15 years of working in and around books I realized recently that there were gaping holes in my engagement with them—namely, I hadn’t been reading drama and that I had never been in a book club. I rectified both problems by starting a club to read contemporary drama aloud with a friend and a little help from Coffee House Press. At our first meeting, eight of us performed Savage Conversations by LeAnne Howe, a series of imagined dialogues between Mary Todd Lincoln and Savage Indian, a stand-in for the Native ghosts that tormented her at the end of her life. In 1862, as the history goes, President Lincoln ordered the hanging of 38 Dakota Sioux in the largest mass execution in United States history; decades later his widow was declared insane by the courts when she claimed that she was visited and tortured each night by a savage. I want to call these dialogues—and occasional monologues by the hanging rope—essentially nonfictional because the circumstances are all true, but they’re also a kind of historical fabulism that defies characterization. As a man from Illinois it was especially challenging to confront the cult of personality that still exists around Lincoln, but performing and discussing this work with thoughtful people was just what I needed. In February, we’re meeting again to read Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, Anne Carson’s blend of the lives of the classical Helen and Marilyn Monroe in a slim little volume out next year from New Directions.

I feel like every honest best-of-the-year list for 2019 will have to include Go Ahead in the Rain and A Fortune for Your Disaster. I loved them both and I sell them avidly, but I’m going to let other people continue to tell you how brilliant Hanif Abdurraquib is and instead bring your attention to five other amazing books by the same publishers: the University of Texas Press’s posthumous reprints of Blood Orchid, Blues for Cannibals, Some of the Dead Are Still Breathing, and Dakotah—the first four books in Charles Bowden’s Unnatural History of the United States sextet—and Jeanne Vanasco’s stunning Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl from Tin House.

The first three of these titles by Bowden were published late last year and I didn’t get a chance to read them until I was on the road with the bookmobile in June. What I read blew me away—alternating paragraphs of gorgeous nature writing and deeply alienated, noirish meditations on the brutality and destructiveness of humankind in general and Americans in particular. Spread across four volumes—so far—this is the narrative of a man on the edge of civilization; the rhythm of his prose is powerful, aggressive, and compulsive, like a hardboiled detective novel. Reading these books is a bleak and beautiful way to lose one’s mind. I burned through the most recent, Dakotah, on my way back from celebrating Thanksgiving and it could not have been a better book for reflecting on who we are as a nation and whose land we’re dining on.

Jeannie Vanasco’s Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl is at once difficult to read and difficult to put down. It is the kind of book that should be required reading for men, but it’s almost impossible to recommend to anyone casually. Vanasco’s memoir recounts her experience as a victim of a rape perpetrated by one of her closest friends from high school, just a short while after graduation. What follows is a succession of complex documents—transcripts of her conversations with her one-time friend, conversations between her and her current partner, between her and her editor, between her and the people close to her, and, most painful of all, her own reflections on these conversations. It’s hard and hard to write something this personal, harder still to strip the process down enough to tell a story that wounded the author so totally in a way that anyone else can understand, but Vanasco does it. This is challenging stuff.

I also read two competing views of teenage masculinity from two very different parts of the world this year. In The Sun on my Head, written by Geovani Martins and translated by Julia Sanches for FSG, Martins’ parables of tender masculinity are so beautifully rendered in such a natural dialogue that it brings us straight onto the blinding beaches of Rio and the desperate walled-in streets of the favela. For Martins, this is home, and his stories are so evocative, so full of life and motion, that I was floored. On the other end of the spectrum, all of the sun-drenched privation of Brazil was replaced by grim skies and relative privilege of Hungary in Dead Heat by Benedek Totth. Translated from Hungarian by Ildikó Noémi Nagy for Biblioasis, this novel is guaranteed to make you fucking squirm in either happiness or discomfort. Following a tight-knit crew of teenage swimmers as they engage in every kind of adolescent depravity, this novel unselfconsciously revels in the easy availability of sex and drugs, booze and drugs, video games, casual criminality, fast cars, and uh, murder. Things take a turn toward toward the psychological thriller in the third act, but the ride is so smooth that it’s easy to enjoy the very nasty drops.

I do love thrillers, that artful remixing of a bunch of familiar tropes into something original and wholly compelling. A Killing for Christ by Pete Hammill, reprinted for its 50th anniversary last year by Akashic, really fits the bill with a full complement of jaded priests, craven church functionaries, really rich Italian nihilists, washed up American party girls, sexually repressed neo-Nazis, and world-weary ex-pat journos—everyone you’d expect to find wrapped up in an assassination plot in and around the Vatican. This melange of characters is wonderfully familiar, like a Christmas dinner with my ex’s family.

And speaking of vintage thrillers with the flavor of home, I also just revisited Sam Greenlee’s The Spook Who Sat By the Door, a social novel of 1969, heroically kept in print by Wayne State University Press. This blistering roast of White liberals and the Black bourgeoisie follows Dan Freeman, the first Black CIA officer, a token trained at the behest of a White senator to appease his Black constituents. Constantly underestimated, Freeman excels in the training program, but he takes his hard-won knowledge of urban warfare and propaganda activities back to the streets of Chicago where he recruits South Side street gangs to set up revolutionary cells and rock Whitey’s world. The place names and people took me back home, but the scenes of police violence against protesters brings this book from a relic of the past into the very real present.

This year, Jeff Waxman is the partnerships director for the House of SpeakEasy‘s bookmobile, a literacy project that provides access to books and book culture in New York City (and beyond!); a bookseller at WORD Bookstore in Brooklyn; a consultant for bookshop.org; and a freelance marketing and sales consultant for book and magazine publishers. He lives in Jackson Heights, Queens.

*

Lori Feathers, Interabang Books

Without any intention it so happens that most of the 80 books that I read in 2019 were authored by women. In retrospect this seems fitting given that my favorite, hands-down, was Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann, a novel that refuses to be anything other than what it is—big, daring, brilliant, and unabashedly feminine!

For “In Context,” a series that I write for Book Marks, I read Ali Smith for the first time, and then devoured each of her ten breathtaking novels. The way that Smith reveals how specific works of art seep into her characters’ minds, altering their perceptions of self, circumstance, and the natural world, feels like a kind of sorcery. While in the midst of Smith’s spell I discovered a worthy complement in Maria Popova’s Figuring, a fascinating study of some of history’s most intelligent women who advanced science by tapping into synergies between art and nature.

For another “In Context” essay I read Edna O’Brien’s brutal, beautiful new novel, Girl, in which a Nigerian schoolgirl is held captive and raped by members of Boka Haram. O’Brien is prolific and shows impressive range in her use of various narrative styles. Of her novels, I most appreciated The Country Girls trilogy (a strong recommendation for fans of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend tetralogy), and her haunting House of Splendid Isolation.

Marie NDiaye is one of my very favorite contemporary authors, and her latest novel to be translated into English and published in the US, The Cheffe (translated by Jordan Stump) did not disappoint. NDiaye is masterful at creating a tone of uneasy disorientation while at the same dissecting the thoughts and intentions of her characters with a clarity and precision that is entirely relatable.

Other 2019 novels that I admired are Jeanette Winterson’s oh-so-smart and provocative, Frankisstein; Debra Levy’s Man Who Saw Everything, an incredibly intricate novel that somehow manages to feel engagingly light (and led me to Hot Milk—read it!); and Fleur Jaeggy’s bitter little pill, Sweet Days of Discipline (translated by Tim Parks).

I discovered Natalia Ginzburg this fall and read three of her novels in quick succession, my favorite being her tiny masterpiece, The Dry Heart (translated by Frances Frenaye), a cross between Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment.

I thoroughly enjoyed and often recommend two of this year’s Booker winners—Jokha Alharthi’s Celestial Bodies (translated by Marilyn Booth), winner of the Booker International and Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, co-winner of the English-language Booker.

I facilitated an engaging book club discussion on Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones), a philosophical novel with many of the attributes of a closed-room murder mystery. Hungry for more, I’m currently reading her otherworldly, Primeval and Other Times (also translated by Lloyd-Jones). Tokarczuk’s writing is lyrical, perceptive and true. Another of Tokarczuk’s talented translators, Jennifer Croft, wrote a beautiful memoir this year, Homesick, about sisterhood, grief, and finding the capacity to heal through language.

A handful of not-so-recent novels that I read for the first time and loved: The Stranger’s Child, Alan Hollinghurst; Mrs. Bridge, Evan S. Connell; Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, Mario Vargas Llosa (translated by Helen R. Lane); An Accidental Man, Iris Murdoch; and Sula, Toni Morrison.

Galley Beggar Press, a tiny UK publishing house, this fall released the extraordinary novel, Patience by Toby Litt, narrated by a young man who is paraplegic and lives in a nursing home run by Catholic nuns. Litt’s writing is sublimely Proustian, and his rich descriptions make Elliot’s interior adventures altogether compelling. It’s no coincidence that Galley Beggar also is the press that first published Ducks, Newburyport.

Of the books I’ve read that are forthcoming in 2020, four novels (again by women) in particular stand out: The Glass Hotel, Emily St. John Mandel; Oligarchy, Scarlett Thomas; Death in Her Hands, Ottessa Moshfegh; and, The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (translated by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin)—a generational saga of 20th century Georgia with the drama and grandeur to be Georgia’s Gone With the Wind.

Lori Feathers is a freelance book critic who lives in Dallas, Texas. She authors the essay series “In Context” for Literary Hub’s Book Marks, as well as Words Without Borders‘ regular feature, “Best of the B-Sides.” Lori is a board member of the National Book Critics Circle, and her work appears in various online and print publications. She co-owns Interabang Books in Dallas, where she works as the store’s book buyer.

*

Kar Johnson, Green Apple Books on the Park

On the High Wire, Philippe Petit

When I opened a package at the store to find this book inside, I was delighted. Physically, it’s a slim volume. Elegant, unimposing. But I knew it would be as eccentric as the man who wrote it.

Philippe Petit is best known for his 1974 high-wire walk between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. By that time, at he had already begun writing On the High Wire, which was translated into English by Paul Auster in 1985 and reissued by New Directions in 2019. High wire walking is an admirable art that seems so impossible, so unlearnable. It’s a discipline that takes a kind of magic. Petit’s work here is written as an instruction manual, though it leaps into metaphor straight away: the high wire as life, the question of balance, the blindfolded walk. It’s at times visceral and thrilling (yes, acrophobia may set in). His love for the wire comes through as poetry on the page and, while his book is meditative, it is still filled with an unexpected humor that comes from someone whose adventures in art have a very real and regular possibility of death.

I Am God, Giacomo Sartori

I so enjoyed Giacomo Sartori’s I Am God (Restless Books, trans. Frederika Randall). I love a novel that takes us from the macrocosm to the microcosm, and this one does so in the most literal of ways. Sartori brings us a God that is—and here I’ll quote Joan Osborne—just a slob like one of us. But he’s more than that. He’s contemplative, he’s keen, and, most relatably, he is fascinated by one being out of the infinite number he has created. That being is a scientist and devout atheist named Daphne, who happens to be one of the most satisfyingly badass characters I’ve read in a long time. With God as our narrator, we are treated to an equally cheeky and philosophical exploration of the universe. His monologue musings guide the reader through switch backs of plot, upending our expectations and showing us a God that does not necessarily give us what we want, but what we need. He’s tough, but fair. He’s an older sibling shrugging you off after a rare tender moment. And you can’t help but laugh when he says, “God forbid.”

Women Talking, Miriam Toews

I read Women Talking (Bloomsbury) several months ago and I still think about it regularly. I anticipate that I will continue to do so. This is the first book I’ve read by Miriam Toews and it was a stellar introduction. The novel is a response to real events which took place in a Mennonite colony in Bolivia where, for years, the women and girls of the colony were made unconscious and sexually assaulted by several men in their closed community, lead to believe for years that the pain and bruises they would wake to find were manifestations of the devil. Toews puts these women in a room together where they must decide whether they will leave the colony or stay and fight.

I have a very low tolerance for reading about rape. I find it, in a word, triggering. I am so glad that I did not let the brutality of the premise deter me from reading this book. Instead, because of Toews’s very capable hands, I was able to look down that barrel, into the heart of the discomfort, anger, and anguish that she renders so skillfully here. The events that have lead the colony’s women to their barn loft meeting place are mere facts that are not made explicit on the page. This allows Toews to bring down to Earth our wide, intangible ideas of morality, God, justice, and forgiveness. The novel is both contemplative and actionable. The reader is left to question whether, when the world we know is broken, do we rebuild from what we have, or do we burn it down? My favorite answer to that question comes from the book itself: “If we don’t want our houses to erode, then we must build them in a different way. But surely we can’t preserve houses that were meant to disappear.”

Please Bury Me in This, Allison Benis White

Whenever someone brought this collection to the counter this year, I told them, “this book fucked me up.” And it did, so swiftly.

Death and grief are among the most frequented topics in my reading repertoire, but in Please Bury Me in This (Four Way Books, 2017) Allison Benis White writes about death with such deft grace and brutal intimacy, it’s difficult not to weep. We find a speaker contemplating the deaths of their father and several women in their life, some of whom have died from suicide, which leads them to the kind of thinking we all do under such circumstances: where does grief end and where do I begin? In thinking too of book as object, the collection meets us with an incredibly paired photograph by the late, brilliant photographer Francesca Woodman, an excellent conversation partner for White’s words. And when we get to words themselves, White puts us in a cold yet enveloping plain, with masterfully employed white space to leave us room to breathe, room to climb the steps of lines like, “Do you think the saying is true: when someone dies, a library burns down?”

White’s next collection, The Wendys, is forthcoming from Four Way Books in 2020 and I cannot wait to read it.

Girlchild, Tupelo Hassman

I wish I could read this book again for the first time. A friend of mine bought it for me at the Friends of the Public Library sale here in San Francisco and told me I’d like it. Two years later, when I knew Tupelo Hassman would be coming to Green Apple for the release of her second novel, gods with a little g, I finally got around to it. I loved gods with a little g (FSG, 2019), but Girlchild (Picador, 2013) was deeply personal for me. Our narrator Rory Dawn, or R.D., is a wannabe Girl Scout who Hassman paints so lovingly and realistically. R.D. Is precocious, but not overwrought. She doesn’t let on to a world bigger than her own child’s understanding, and that closeness of reader to narrator worked to floor me by the time some plot twists crept up on me. And the Calle, the dusty Nevada town R.D. calls home, is an incredible beast of a background. Tupelo Hassman is masterful with words. Short, bursting blocks of prose create a hungry momentum I couldn’t get enough of. Harsh, boozy trailer parks. Smoke-filled casinos. Latchkey kids. I want to stay in the world of Hassman’s novels forever. Read this. And when you do, give R.D. a hug for me.

How We Fight For Our Lives, Saeed Jones

I read more memoirs this year than I ordinarily do (other favorites from this year’s reading were Kiese Laymon’s Heavy and iO Tillet Wright’s Darling Days), but something gripped be about Saeed Jones’ How We Fight for Our Lives (Simon & Schuster). It was more than a grief memoir. It was more than a coming out memoir. What I loved about this book was how it tackled the nuances of coming into your own as a queer person. How your family can in one instance deliberately show you the beauty and difference of a world in which queer people live and thrive, and in the next insist that that life is not for you, not their child. It shows the fear parents carry for their queer children. It shows that loving your queer child is not always loud, but is sometimes quiet understanding. This is a book about tethering and untethering, in which you cheer Jones on as he becomes more of himself. It’s a poetic progression with the accompanying growing pains. “People don’t just happen,” he writes. “We sacrifice former versions of ourselves. We sacrifice the people who dared to raise us. The ‘I’ it seems doesn’t exist until we are able to say, ‘I am no longer yours.’”

Kar Johnson is a writer, performer, educator, and bookseller in San Francisco. Their writing has appeared in or is forthcoming from The Northridge Review, Foglifter, and the anthology Love is the Drug and Other Dark Poems. Kar has performed their work for series Red Light Lit, The Racket, RADAR, and many others. They received their MFA from San Francisco State University and work at Green Apple Books on the Park.

*

Emma Ramadan, Riffraff Bookstore and Bar

2019 was a year marked by three books in particular for me, all about women enmeshed in excruciating affairs. I read Ariana Harwicz’s forthcoming Feebleminded, translated from Spanish by Annie McDermott and Carolina Orloff, two times, and both times it was somehow just as unpredictable, just as jarring, just as breathtaking. It’s a wild ride about a horny mother-daughter team out for blood and revenge. Natalia Ginzburg’s The Dry Heart, translated by Frances Frenaye, tells the story of a woman whose husband is hopelessly in love with another woman. She, too, gets her revenge. And Renata Adler’s Pitch Dark, a gem from 1983, is simultaneously one of the most boring and one of the most crushing, knock me out, wipe the floor with me, soul-shattering books I’ve ever read. After a nine-year affair with a married man, Kate is seeking her own form of freedom. Mirroring Kate’s cyclical inner battle, Pitch Dark uses repetition to insane, baffling effect.

I also read Lucia Berlin’s Manual for Cleaning Women and the follow-up, Evening in Paradise (the follow-up, but thankfully not the dregs). Berlin’s stories are so wildly honest and charming. I could read her for hours, days on end.

There were also a few fantastically weird novels, including the darkly humorous Banshee by Rachel DeWoskin about a woman with breast cancer who’s convinced she has three weeks left to live, and who gives herself permission to act however she’d like. There was Halle Butler’s The New Me, a cringe-inducing, hilarious depiction of one woman stuck in a spiral of depression and narcissism faced with the pointlessness of her existence. And there was Annaleese Jochem’s Baby, a total thrill ride about two women who run away with stolen money and buy a boat to live in bliss, before things quickly take a series of strange and stranger turns. I ate it up.

There was also Danielle Dutton’s SPRAWL, a perfect, manic treatment of suburban life. And Marcy Dermansky’s Bad Marie, about a deplorable woman who steals her friend’s husband only to lose him to another woman as soon as they’ve absconded to Paris. And I went on a Kate Zambreno spree during a month of travel, tearing through O Fallen Angel, Green Girl, and Screen Tests on planes and in hotel rooms. There was also the devastating Love by Hanne Ørstavik, translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken, to read only when you’re in a good emotional place, but well worth the tears. And the maybe-memoir maybe-novel Homesick, a stunning meditation on sisterhood and language by Jennifer Croft. And Black Forest by Valérie Mréjen, translated from French by Katie Assef, a little paradoxically lovely book about death.

Of course there was Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, and Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys, and Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans. Of course there was Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror and Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House.

The other nonfiction books I read that will stay with me are Hanif Abdurraqib’s Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, and Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias. There was the cinematic Rough Magic by Lara Prior-Palmer, which I blazed through in one multi-hour sitting, unable to hold back actual gasps. There was the devastating When Death Takes Something from You Give it Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt, which was also the most formally experimental book I read this year, showing how grief will refuse and overflow prim structures.

And there is always poetry. I especially enjoyed Elaine Kahn’s forthcoming Romance or The End and Jericho Brown’s The Tradition. And then there was Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s searing Scorpionic Sun, a book that will give you whiplash. A work, and a translation from French by Conor Bracken, that defies how we understand language and gives us a blueprint to decolonize literature, hopefully a sign of what awaits us in future years as more and more presses dare to publish bold books in translation.

Emma Ramadan lives in Providence, RI, where she co-owns Riffraff bookstore and bar. She is also a literary translator of works including Sphinx by Anne Garréta, Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes, and a co-translation of Me & Other Writing by Marguerite Duras. She is the recipient of a Fulbright, an NEA Translation Fellowship, and the 2018 Albertine Prize.

*

Deborah Reed, Cloud & Leaf Bookstore

I purchased a copy of Milkman by Anna Burns in Reykjavik at the end of last year, and it was there that I began reading this fever dream of a novel. It seems fitting that inside 18 hours of darkness in a land of fairies, and reindeer on the menu, I swam along disoriented in this stream-of-consciousness story. I’ll be honest, it took two months to finish.

At times I grew frustrated from groping blindly while the plot meandered, somehow lightning fast and gradually at once, before hitting me with a wallop, which I began to trust that it would, and this became the payoff. Burns comes at everything slant, portraying “The Troubles” in Ireland through the eyes of a young woman who wants only to read literature while walking down the street in a town with no name, though we understand it is Belfast, just as we understand so many other hard truths about this fractured society without having to look at them directly. And this is the genius of this book, the way Burns can tell us a story we already know, presenting it as new and original, with a voice we’ve never heard, and the ability to change what we think we know about this conflict in Ireland.

Late winter, and the Oregon coast where I live settled into the steady rain it is known for, and I settled into an advanced reader copy of Olive, Again. What an absolute pleasure to have these two things at once. My husband remarked several times how nice it was to see me laughing and sighing and tsking and groaning while reading a book by the fire. I was so fully engaged I had no idea I was expressing any of it out loud. I gave myself over to this novel, and I did not want it to end. Who could have imagined that Olive Kittridge would ever come back to us? I suppose part of it was the fact that I had Frances McDormand and Bill Murray in my head as the characters, due to the HBO series of Olive Kittridge, and, hey, that was an absolute delight, too. Olive is one of the great miserabalists, as the NYTBR called her. And now that the book is finished I miss her all over again.

I started reading The Friend by Sigrid Nunez at the same time as my son Dylan, who is an author events manager at Skylight Books in Los Angeles, and the texts between us fired up immediately, and continued until we were both finished. How did she do that? Oh my god. How far are you? The meta-fiction of this is genius. Yowza, she’s so good! Oh no, get ready! The Great Dane at the center of the story is the elephant in the room, which is the loss of a close friend to suicide. And yet the dog stands for hope for the future, for connection, a way out of the sadness that is bearing down (though slyly) on the protagonist. And all of this is achieved using second person, which is a feat unto itself. After finishing this novel something struck me and, as it turns out, has sustained me throughout this entire year, and that is that our current dark times we’re living through are producing some really great books.

Speaking of dark, can we talk Women Talking? As a huge fan of Miriam Toews, I couldn’t wait to get my hands on this one. Recently, Lauren Groff wrote on twitter that 40 years from now this book will hold up as a classic, and I perfectly agree. It is based on a true story of Mennonite women and girls in Bolivia, who were waking up with no memory having been assaulted in their sleep, but bore the evidence that they most certainly had. I’ve read this novel twice to see how Toews pulls off a story that is so suspenseful and so melancholy at once. It is speculative fiction and pure realism rolled into a deceptively simple story, reminiscent of The Handmaid’s Tale. In the end, the consequence of what the women decide to do with the men accused of abusing them is far-reaching, and reverberates across all borders and time.

I read two books that reminded me a lot of each other: Aug. 9-Fog by Kathryn Scanlan, and Ash Before Oak by Jeremy Cooper, each lovely and strange, written as diary entries, and infused with sadness and stillness and a looming threat. These stories may feel obscure or too experimental for some, and I’m hesitant at times to recommend either to customers in my store unless I get a strong sense that they appreciate poetic prose and are willing to forgo plot. Reading these works is like watching a small independent film where not much happens but you are not there to see something happen. You are there for the writing and the mood. You are there for the art of the whole. What’s wonderful is when a customer I sense might be interested, turns out to be really interested, and snatches one of these books to their hearts. I feel then as if I’ve had a brush with a kindred spirit, and off they go, leaving me humming behind the counter.

Which brings me to Homesick by Jennifer Croft. As I posted on my bookstore’s social media accounts directly upon finishing this wonderful book, I clutched it to my chest. It’s a beauty! You may know that Croft is the translator for Nobel Prize winning Olga Tokarczuk’s book Flights, which gave both women the Booker Prize in 2018. Croft’s own book, Homesick is marketed as a memoir, but I caution readers against this, explaining what a hybrid of work it is, written in third person, while including photographs taken by the author with inscriptions beneath that are written in first person. The effect has the reader floating in and out—distant, then close—and the overall effect is like drifting inside memory itself, which is never quite linear, sometimes just out of reach, other times so close it’s as if what is remembered is happening now, visceral as our bodies absorb it. Croft is a brilliant woman by anyone’s standard, entering university at 15 years old, and speaking a multitude of languages. She has a unique, interesting, and heartbreaking story to tell, and the structure in which she tells it shapes it into an even more sympathetic artform.

And so it goes with Late Migrations by Margaret Renkl. I was dazzled upon my first read, and my affinity with this book continues to grow as I revisit passages that move me every time. In my own writing I often fall into themes of the natural world, grief, art, beauty in the dark, and the messy, complicated dynamics of family members—all of which is found in Late Migrations. Renkl’s essays on the natural world are often published in the New York Times, but having a narrative collection that travels across time with her and her family, through losing a homestead and loved ones and dogs, and then pausing in between to admire the gorgeous illustrations from her brother, is a kind of multi-media experience of having been to an art museum. Late Migrations is a contemplative and generous book about love and loss, and is one of my favorite books of the year.

The final two books that I chose for this list are not out yet, but I am so looking forward to their releases and being able to discuss them with customers, that I want to mention them so that readers will keep an eye out. They are Weather by Jenny Offill, and Becoming Duchess Goldblatt by, well, Duchess Goldblatt, who remains an anonymous person on twitter.

I read both of these books while on a trip to New Mexico this fall. Weather by Offill, whose previous novel Dept. of Speculation, was a stunner, and one I used while teaching novel writing as co-director of a writing program at the University of Freiburg in Germany every summer until recently when I bought my bookstore. I loved seeing that dawning expression come over students’ faces when they realized what Offill was doing with language and changed their idea of what a novel could be. Weather feels like a continuation of Dept. Of Speculation, written with the same style of piercing vignettes, and with the same wry approach to depression, motherhood, and marriage, as well a quiet infusion of wonder and hope at how the universe is put together. One of the beauties of Offill’s work is the way in which dark epiphanies mix with a tenderness, with love itself, and seep through the cracks so slowly that they appear before we’ve even realized what hit us. This novel was the perfect companion for New Mexico, where a tarantula nearly ran across my foot in the desert just before I saw a rattlesnake, all underneath a painfully blue sky and sand colored cliffs and red dirt. Everything felt spare and beautiful and sure, on the brink of death.

Becoming Duchess Goldblatt is a memoir of an anonymous person on twitter with a real life story to tell that will make you laugh and cry and yearn so badly to find out who she really is, but also mix you up because you see yourself in her words, recalling days of loneliness and uncertainly, of being responsible for a child you love more than the air you can hardly breathe at times, and it dawns on you that this person’s anonymity should be protected at all costs. Your fondness is fully given over, in the same way a fictional character pulls us into a contract where we agree to be cracked open and rearranged and put back together with a brand new shape. When you read this thoughtful and heartbreaker of a story about the Duchess coming to be an anonymous character on twitter, who turns out to be someone with an unmatched wit who never fails to move complete strangers with her genuine affection for this world, you end up wanting her grace, as she’s often referred to, to remain in the safety of her bubble. Don’t touch her. Don’t ask anything of her. Just let her have everything she asks for from this world, and more.

Deborah Reed is an author of several novels. Her forthcoming, Pale Morning Light With Violet Swan will be published with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in June of 2020. She is also the owner of Cloud & Leaf Bookstore in Manzanita, Oregon, and independent located two blocks from the Pacific Ocean. www.cloudleafstore.com

*

Lexi Beach, Astoria Bookshop

My year in reading began on New Year’s Day, when I finished The Widows of Malabar Hill by Sujata Massey. I love mystery novels, though I’m not as avid a reader of the genre as I was in my teens. These days, I try to read a new-to-me author once a year, in part so I can have a broader range of opinions for my customers about ongoing series. I had been noticing lately, though, how few of the mysteries I was reading (and that we carry, and that my reps sell me) are written by women of color. Where is the Japanese Tana French giving us the Tokyo Murder Squad? Where is the #ownvoices No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency? And then I learned about the Perveen Mistry series.

Massey is an established author, but this is the first of a newer series from her (book two was released this past spring), featuring Perveen Mistry, a young Parsi lawyer based loosely on the real-life woman who was the first Indian woman lawyer admitted to the bar. Her gender and occupation make Perveen the only lawyer able to work closely with a family of Muslim women living in seclusion after their husband passes away. This solid, smart mystery delves into issues of women’s rights, India’s self-rule, and the ways a multi-cultural society functions. It felt like an Indian variation on Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, which is exactly what I wanted.

January is when booksellers, barely recovered from the rush of Holiday Retail Madness, step away from their stores for an intense trade conference called Winter Institute. There’s little time for reading at the conference, but most of us have lengthy plane trips there and back, often extended further by inclement winter weather. So I read a lot of great books in January, in various airports. One standout was Light from Other Stars by Erika Swyler, a beautiful, brainy, literary science fiction novel. It’s a coming-of-age story combined with a tale of scientific exploration, beginning with the 1986 Challenger explosion and stretching forward to an advance mission by a team of astronauts looking for a new home for the human race. At the center is a bright young girl named Nedda who is trying to find her place in her secret-filled family and the confusing world around her.

I made a side trip to see some family during Winter Institute, which gave me a few long stretches in a car. I took advantage of the opportunity by finally listening to Michelle Obama narrate her memoir Becoming. I’m better at comprehension when I’m reading a printed book, but there is a certain kind of memoir I would much rather listen to on audio, and this one does not disappoint. Mrs. Obama delivers a wonderful performance, and hearing her tell the story of how President Obama (then just Mr. Obama) proposed to her is worth the price of admission and the 19-hour run time. I still can’t believe she said yes. (Incidentally, if you’re wondering how long a book might take you to read, I recommend checking the run time of the audio edition.)

The best book I read this year was also a memoir, Mira Jacob’s graphic novel Good Talk. Broadly speaking, it’s about being a woman of color in America and raising a mixed race son through Obama’s presidency and Trump’s election. The book is structured as a series of conversations, beginning with questions Jacob’s young son starts asking, about his own place in and observations of the world, and goes back to her own childhood as the daughter of immigrants. It is beautiful and sad and very funny, and beyond that, feels like a necessary book for our times.

In theory it’s my job as a bookseller to recommend books to my customers, and to keep up on new books that are coming out. In practice, it also works in the opposite direction. Greenglass House by Kate Milford has become a steady best seller for middle grade readers, but the mother of one such reader expressed to me that the author’s earlier books are even better. So I picked up Boneshaker, her spectacular debut set in a small town in 1913 in the middle of the country. I would, without reservation, recommend this book to any fantasy reader over the age of 10. The main character is a 12- or 13-year-old girl whose father is a mechanic. A traveling medicine show, featuring some creepy as hell automatons, comes to town, and basically all hell breaks loose. It’s a story about morality and the soul and the devil and the cost of asking hard questions and the cost of not taking sides.

At the beginning of the year, I was the only person working at my store who had not yet read Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties. I finally rectified that about 80% of the way over the summer. This collection has rightfully accrued so much praise from readers and reviewers and my own staff and customers that the only thing I can add is why I didn’t finish the book. I read up through the story “Real Women Have Bodies,” my emotional state gradually deteriorating until I collapsed in tears completely at the story’s conclusion. I put the book aside and have not picked it up again. If you, like me, have a partner who is disabled by an invisible chronic illness that statistically affects women more than men, I would recommend approaching that story with caution, but I would still recommend the book.

After that, I decided to read a bunch of romance novels, the best of which was Red, White & Royal Blue by Casey McQuiston. I loved this book SO MUCH. It is the gay fantasia on national themes that we need right now. It is charming, funny, and sexy, the perfect escapist read for troubled times. I cried happy tears at least once as the happily-ever-after ending unrolled, and I spent more than a few minutes looking for fan art on Instagram.

My parents both read a lot of international spy fiction when they were younger, and in high school I tore through their collective library of Le Carre, Forsyth, MacInnes, Ludlum, et al. I was obsessed with J.J. Abrams’s show Alias to an unhealthy degree, and I started watching Burn Notice after a friend relayed the assessment of a friend of hers who works in private military that it was pretty accurate on operational details. Amaryllis Fox’s memoir Life Undercover is a book tailor made for me.

If you ask me about this book in person, I will get very animated and force you to hear about where on the body Aung San Suu Kyi advised young Amaryllis (pre-CIA recruitment, when Suu Kyi was still under house arrest) to hide a roll of film that held a recording of an interview with her. I will tell you all about Fox’s British grandmother, who was something like a cross between Lucille Bluth and Tahani Al-Jamil’s parents, forcing Amaryllis and her adopted uncle to physically compete (presumably for her affection). Let me tell you about her first marriage, to a college boyfriend, which happened because she wasn’t emotionally mature enough to break up with him but didn’t have clearance to live with a foreign national unless they wed. And on and on.

Fox is a remarkably good writer, and I learned so much spycraft reading her stories about her fieldwork. Come for the ridiculous eccentric WASP family antics, stay for the international secret agent intrigue. Or the other way around.

I finished up my 2019 reading with another customer recommendation. I had slept on This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone, but after one customer said she was buying it after reading a library copy, and another assuaged my concerns about the time travel aspects of the story (Harry Potter 3 will never be my favorite of the series because the time travel plot just doesn’t work), I read it. It is far better than I could have expected. It’s Spy vs. Spy meets The Time Traveler’s Wife, presented as an epistolary SFF romance novel. It reads like a collection of increasingly steamy love poetry. That is A LOT to ask of a 200-page book, but this one delivers beautifully.

*

Josh Cook, Porter Square Books

After tweeting my way into a copy of the new Norton Critical edition of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, I decided to make a light commitment to reread some books this year, starting with that one. So I gathered a stack from my shelves and plan to continue making my way through it, even if I can only get through a handful a year.

Some of those rereads were like visiting with old friends, like Tristram Shandy and Uncle Toby and Brentford and Gabriel in Aurarorama, while in others I saw themes and currents I missed the first time around, like the politics and economics of racism in Big Machine (which I’m almost embarrassed to have missed) and the empathetic nihilism at the core of Mario Bellatin’s The Beauty Salon.

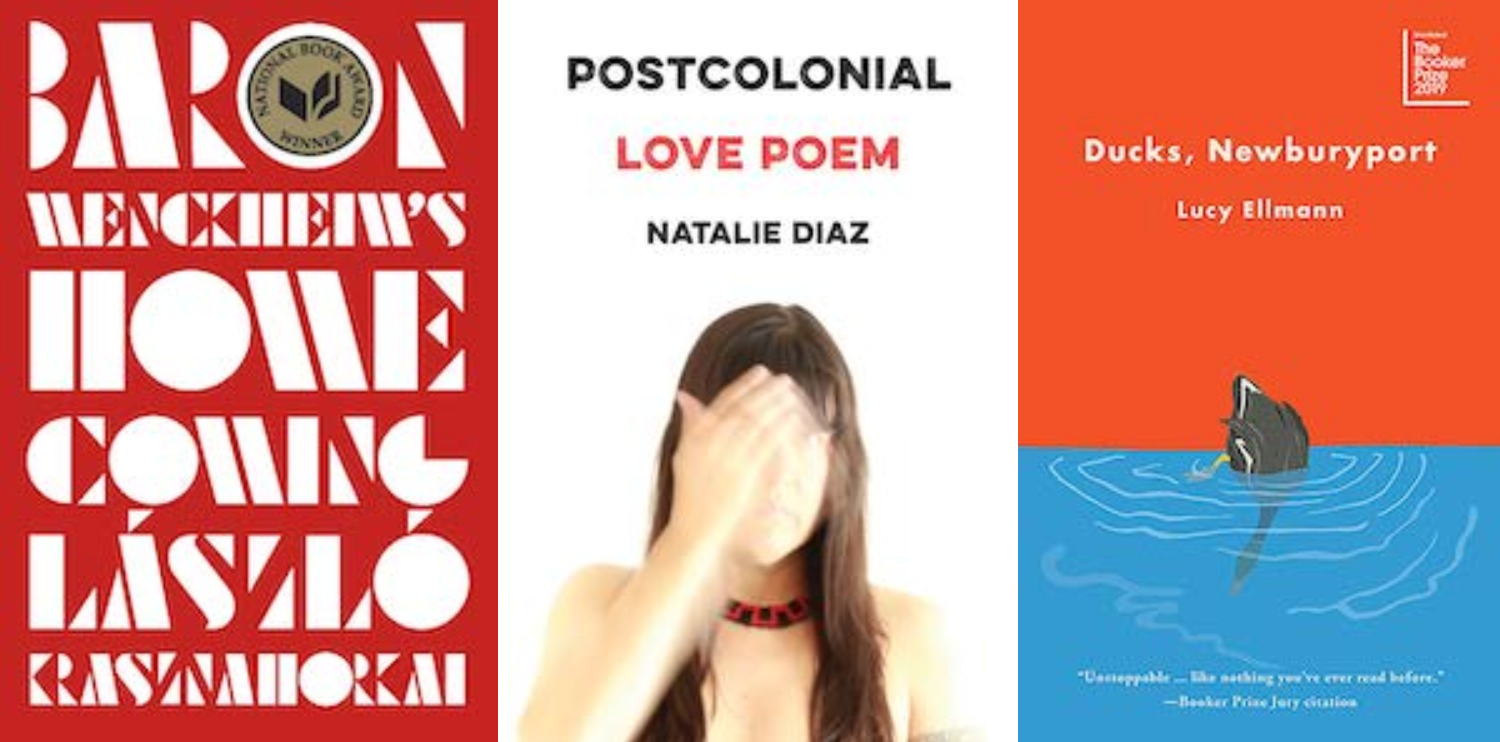

2019 was also the year I saw Valeria Luiselli take another step towards the international literary superstardom she deserves with The Lost Children Archive (which I technically read in 2018), read my friend and bookseller colleague Rebecca Kim Wells intelligently undercut the chosen-one narrative arc in her bisexual, politically cogent, and angry YA fantasy novel Shatter the Sky, read my friend Nina MacLaughlin transform Ovid into a fleshy, furious, and feminist new version of itself, discover on Twitter (like any old reader) the subtle brilliance and disturbingness of An Untouched House (hat tip to Gabe Habash), introduced myself to Charco Press through Die, My Love, encountered one of the great images of novel writing in Krasznahorkai’s genius and National Book Award-Winning Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, had my worldview completely changed by Ibrahim X. Kendi, started banging the drum for Natalie Diaz’s March 2020 collection Postcolonial Love Poem, and read my way through a few dozen other weird, challenging, baffling, and fun books. (You can see them all here: https://twitter.com/hashtag/JoshRead19?src=hashtag_click&f=live)

But now that I’m a couple of paragraphs in I realize that my 2019 in reading is the year of Ducks, Newburyport. A fellow bookseller grabbed a galley for me from Winter Institute and I started it almost as soon as it was dug out of the box. Because as soon as it was dug out of the box, I saw the publisher copy on the cover, written, as I would learn, in the style of the book itself. The copy was so compelling I tweeted a picture of it. And then the book itself was so compelling I live-tweeted much of it as well, something I’ve never really done before. I even started adding post-its and notes to the galley as I read (notes like “Oh no oh no oh no” and “Ahhhhhh!”) which I’ve also never done in a galley before.

What might be most interesting to me, at this point in the young life of the book, is how readers and critics, even those who praise it, get aspects of it wrong. There are many sentences, not just one, in the book. The vast majority of them are about the mountain lion, of course, but even though there is only one period in the stream of consciousness portions of the novel, it’s organized in sentence units. The full stops are created by the repeated phrase “the fact that,” rather than a period. Many have called it plotless, even though there is rising action, character development, tension, even dramatic irony, and about as traditional a climax as you can imagine. The stream of consciousness voice just sometimes asks us to imagine the external events inspiring her reactions. A lot of readers assume it is going to be an abstract, contemplative, and fundamentally interior novel and though it is interior and can be abstract and contemplative, it also has some of the best scenes in 2019; funny scenes, horrifying scenes, funny and horrifying scenes (like the flood while they’re at the mall), scenes that are etched into my memory. It has heroes and villains. Dynamic characters and static characters. It critiques systems of power and it focuses on individual actions and decisions.

In some ways, Ducks, Newburyport is a bait and switch; it looks like one of those massive postmodern tomes, a book like Witz or A Naked Singularity, and it seems like many readers and critics, again including those who praised it, held on to that first impression, reading into a type of difficulty that is not present, interpreting supporting mechanisms as main ideas, assuming that Ellmann is simply using techniques most often used by male writers in the past to explore the idea of women’s work, rather than seeing how Ellmann’s fundamental and unshakeable respect for a character often edited out of history creates something completely distinct from typical postmodernism. Ducks, Newburyport is really a classic work of modernism, a continuation of modernism’s grand humanist project, Mrs. Dalloway by way of Molly Bloom through Kate Chopin, Gertrude Stein, Mary Butts, Mina Loy, and Djuna Barnes.

And now there’s a chance the Porter Square Books could sell 100 copies or more of Ducks, Newburyport in 2019; 100 or more copies of a 1,000-plus page, in mostly one sentence, with the plot events buried in the stream of consciousness of the protagonist, published on this side of the Atlantic by a small press from Canada, novel written by a woman. I don’t entirely know what that means, whether it says anything about publishing or literature or bookselling or anything different from when Coffee House published A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing or Archipelago published Knausgaard’s My Struggle. Publishing is an ecosystem and just like in ecosystems, there is never a singular explanation for or effect from any phenomenon.

Well, there is one thing I know for certain. If PSB hits the century mark with Ducks, Newburyport, I’ll be getting another literary tattoo.

*

Emily Miller, The Ivy Bookshop

2019 was the year I had to train myself to read again. To explain:

Last summer concluded with an unforeseen tragedy, and I spent the remaining months of 2018 treating my grief like the toppling pile of unwashed laundry spilling out of my closet: I acknowledged it, sure, but I mostly willfully ignored it. September through December I read near-constantly and listened to hundreds of hours of audiobooks, terrified by the notion that I might be, at some point, left alone with my own thoughts. Avoidance is a skill I mastered with pride. Utilitarian as it was, I cherished the time I spent living in worlds other than my own, and I ended the year having read nearly 100 books without really trying. The number wasn’t the thing that mattered so much, but rather what getting there had come to represent: security, comfort, joy. Survival.

As it turns out, though, grief is exhausting and impossible to outrun. I woke up in January and suddenly found myself tired in a way I’d never felt before—the kind of tired that you feel deep in your soul and that no amount of sleep could ever hope to resolve. I leaned into the exhaustion, comfortably succumbing to the infinite scroll of my phone, and before I realized what had happened, I stopped reading altogether. I thought it would be a short-lived phase, a sabbatical from books. I called it rest, self-care. It was never any of those things. I’ve spent the remainder of the year cycling between the guilt and shame of losing my will to read and the fervor of getting it back for brief but intense spells and remembering its familiar sensations. Retraining my brain to want (and love) to read again has been onerous but rewarding in its own varied ways, and though I’m still finding my footing, I think I’m almost there. It helps that I spend every day surrounded by books and some incredibly smart people who are always excited about them.

A little on the nose, but the first book this year to pull me out of my slump in earnest was Kristen Arnett’s marvel, Mostly Dead Things, an incisive tale of loss and love and all the things that come before and after. Arnett’s taxidermist Jessa-Lynn Morton asks, “How to leave the past when it’s staring you in the face all the time? When it’s got its teeth dug into you like a rabid animal?” That was the very same question I’d been asking myself every day, and seeing it on the page ignited something in me. It was a bright spot. It was hope.

My affinity for the simultaneous ugliness and beauty of Mostly Dead Things easily translated to some of the other books I discovered and loved this year during similar periods of motivation, like Lara Williams’s underrated Supper Club (an urgent exploration of hunger—both literal and metaphorical—and macerated anger) and Halle Butler’s utterly grotesque The New Me, which I’ve crowned the definitive millennial burnout novel. It felt a little too real—the secondhand anxiety made me squirm and sweat—but I devoured it whole.

Thematically speaking, Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation felt like the natural next selection, The New Me’s cool older sister. It took me months to work myself up to it but once I finally opened it, I fell madly in love. (I’ve since worked my way through the Moshfegh backlist and have fallen deeper and deeper each time.) There’s a revelatory excerpt I have saved on my phone that I pull up every now and again as a reminder that everything I’m feeling has been felt before and will be felt again, and it comforts me: “I could think of feelings, but I couldn’t bring them up in me. I couldn’t even locate where my emotions came from. My brain? It made no sense. Irritation was what I knew best—a heaviness on my chest, a vibration in my neck like my head was revving up before it would rocket off my body. But that seemed directly tied to my nervous system—a physiological response. Was sadness the same kind of thing? Was joy? Was longing? Was love?”

After My Year of Rest and Relaxation I fell back into another slump—a long one. When I finally dug myself out, I realized that summer had arrived without my noticing, and so I celebrated it with graphic novels savored over long afternoons on the porch with hot sun and cold beer. Mira Jacob’s Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations, which is incidentally the first graphic novel I’ve successfully hand-sold to a skeptical purist, and Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’s Saga, which was recommended to me by a close friend and now occupies prime real estate in my heart, are the ones I’ve shouted about the most since then.

With that momentum under me, I really leaned into single-sitting reading, and some of the other books I consumed this way and enjoyed most were Fleur Jaeggy’s slim and unsettling Sweet Days of Discipline, Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends, (which I will controversially declare the superior Rooney novel) Samantha Hunt’s dreary, haunted, maybe-mermaid novel The Seas, and Eduardo Lalo’s sensual not-quite love story Simone, which I read almost entirely in a jacuzzi on the roof of a former convent in Old San Juan. (As far as reading spots go, I can’t recommend a better one.)

Because I read so erratically, I spent much of 2019 anxiously pondering the selection of each subsequent book, and the one I contemplated most of all was Anne Boyer’s genre-bending cancer memoir, The Undying. An advance copy sat on my shelf for months, untouched, while I debated whether it would bring up too-painful hospital memories (which it did) or whether it would be cathartic (which it was)—but I’m grateful to have finally picked it up towards the end of this year. It’s rage-filled and essential and brave, and it reminded me that sometimes, in order to heal, you need to read to remember and not to forget.

I’ve been slowly working through a tall stack on my nightstand since then. I can’t say I’m back to where I hoped I’d be in my reading life, but I’m getting close enough that every page feels like a triumph. And that’s good enough for me.

Emily Miller is the operations and events manager at The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore, Maryland. Twitter: @emily_f_miller