The Booker Revisited: Why Everyone Should Read Francis King’s The Nick of Time

In a New Series, Lucy Scholes Reads the Booker Prize Titles of Years Past

Gathered together on the Booker Library’s virtual shelves is a unique collection; every title that’s been longlisted for the Booker or International Booker Prize since the former’s inaugural year back in 1969. That’s over 50 years of great fiction, written by some of the brightest minds, that together constitutes a fascinating and illuminating history of our times. Many of these titles are household names, still read widely enough today to need no introduction. But there are others that have slipped out of sight over the years; some—despite their illustrious history—have even fallen out of print.

These are the novels I’m interested in; those that constitute a forgotten Booker Library, if you will. Every month I’m going to be re-visiting one; examining its place in the prize’s history, and the wider context of the era in which it was first published, but first and foremost, hopefully giving you a reason to pick it up today, however many years after it first made the headlines. I can promise you dark horses, one-hit wonders, and various famous authors’ lesser-known works aplenty, with apologies in advance for adding to everyone’s already tottering To-Be-Read piles! First up is Francis King’s The Nick of Time.

*

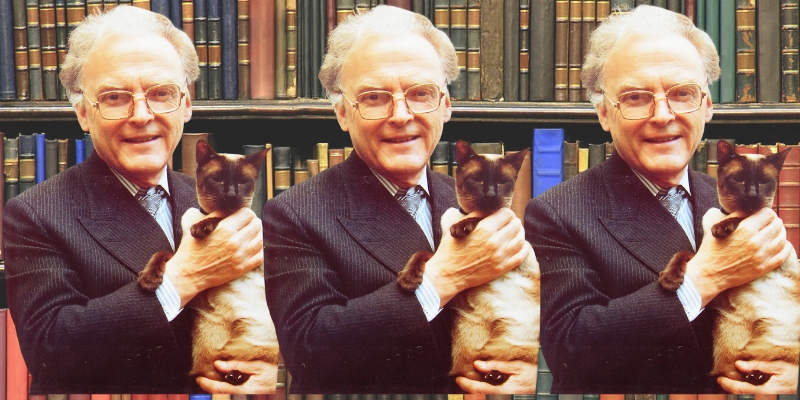

King’s first novel, The Dark Tower (1946), was published when he was still an undergraduate. Such precocity has its downsides though, as he told the writer and editor Kay Dick thirty years later when she interviewed him for her book Friends and Friendship (1974). People, he explained, “can remember you as having been a writer for such a long time that they think you must be an octogenarian.” As it turned out, King would have to wait until he really was an octogenarian before he received his first nomination for the Booker Prize. In 2003, the year he turned eighty, his twenty-eighth novel, The Nick of Time, finally made the longlist. Once “tipped as the most promising writer of his generation,” lauded The Times, King was finally getting his due.

Obviously, there are plenty of excellent writers who fail to receive the distinction of a Booker nomination, but King did seem unluckier than most. Over the course of a career that spanned six decades, his writing went from strength to strength. His fourth novel, The Dividing Stream (1951), won the Somerset Maugham Award, and his second collection of short stories, The Japanese Umbrella (1964), was awarded the Katherine Mansfield Short Story Prize.

In 1978, A.J. Ayer, the philosopher and chairman of that year’s Booker judges, apparently took the opportunity of the prize dinner to express his opinion that King’s novel The Action—which was inspired by the complications of a libel case that King had found himself entangled in following the publication of his autobiographical novel A Domestic Animal (1970)—should have been on the shortlist. And six years later, Auberon Waugh insisted that King’s Act of Darkness (1984) was the outstanding novel of the year, and it was a travesty it hadn’t been nominated for the Booker.

“A writer’s writer, his voice utterly convincing,” praised Beryl Bainbridge, comparing King’s talents to those of Graham Greene and Nabokov. Melvyn Bragg declared him a “master novelist,” while A. S. Byatt pronounced his writing “always accomplished and elegant.” When King died, age 88, in 2011—by then the author of fifty books—The Scotsman described him as “one of the finest and most remarkable of English novelists of our time.”

Yet he remains sadly under-appreciated today, and the majority of his books are out of print. This is all the more unfortunate because not only was he an extraordinarily accomplished storyteller, never content to rest on his laurels and write the same book twice, he had an outlook on life that set him apart from the pack.

When King died, age 88, in 2011—by then the author of fifty books—The Scotsman described him as “one of the finest and most remarkable of English novelists of our time.”

After graduating in 1949, King got a job with the British Council. He then spent the next fifteen years living abroad—in Italy, Greece, Finland and Japan—experiences that afforded him a much more cosmopolitan mindset than many of his peers who hailed from similar public-school- and Oxbridge-educated, traditional middle-class English backgrounds. (King was born to English parents in Switzerland in 1923—where his father, a senior official in the Indian Police, was being treated for TB—and then spent his early childhood in colonial India, before being sent back to boarding school in England.) He was also openly gay, having “come out of […] refrigeration,” as his friend the writer Angus Wilson put it, after being “seduced” by a gondolier on holiday in Venice before beginning his final year at Oxford.

As his candid autobiography Yesterday Came Suddenly (1993) attests, despite the broader ignorance of the world around him, King himself was quite at ease with his sexuality (more so than many of his youthful partners), and homosexual characters often appeared in his novels, even during the pre-Wolfenden era when this was not without its dangers. (The British Council considered The Firewalkers (1956)—a roman-à-clef based on King’s experiences in Salonika—so potentially scandalous, for example, that they insisted that he either publish it under a pseudonym or resign from his job.

He opted for the former, and the book appeared as the work of one Frank Cauldwell—the name of one of the characters in The Dark Tower, a young novelist who falls under the spell of an older, celebrated writer, war hero and adventurer.) This is not to say, however, that King was always happy. “In my early books, written at a period of loneliness in my own life, isolation is a recurrent theme,” he confessed in the early 1970s, looking back to the beginning of his career.

Perhaps most noteworthy of all though is the fact that age did little to diminish King’s talent. He might well have been something of an “old-fashioned man of letters who relies on his pen and whose position grows ever more precarious with each new lurch in book-trade economics,” as the critic, novelist and biographer D.J. Taylor once admiringly put it—but the same certainly couldn’t be said of King’s writing. His “openness to experience and interest in other people kept him writing into old age as freshly and perceptively as in his youth,” noted The Scotsman, praise that would no doubt have pleased the man himself.

“I feel that I’m writing probably my best work,” he told The Times when The Nick of Time made the Booker longlist, “but I do not feel it’s getting the recognition it should have.” He wasn’t wrong—although the novel had been published in April, most broadsheet reviews didn’t run until the Booker longlist thrust the book into the limelight that autumn. As Taylor observed, King was one of the very few writers still “capable of surprising their audience” in their twilight years, and nowhere is this more in evidence than in The Nick of Time: an eye-opening, contemporary state of the nation novel that paints a vivid portrait of London in the very first years of the twenty-first century.

At the centre of the story is Mehmet, an illegal Albanian immigrant, whose itinerant adventures in the English capital are the thread that links the lives of a small group of otherwise disparate city-dwellers together. He first appears as a knight in shining armour, coming to the rescue of Meg—an older widow, afflicted by MS—when her electric wheelchair awkwardly decides to give up the ghost on a pedestrian crossing. “It was as though God had sent him to me,” she later tells her sister, Sylvia. “More like the Devil,” thinks Sylvia. Angelic or infernal? Mehmet is a little of both. His charisma sees him charm his way into other people’s lives with apparent ease. First there’s Meg, whose lodger in the spare room of her Dalston council flat he swiftly becomes, paying his way by helping her around her home and offering her some much-needed company.

At the centre of the story is Mehmet, an illegal Albanian immigrant, whose itinerant adventures in the English capital are the thread that links the lives of a small group of otherwise disparate city-dwellers together.

Then there’s delicate and damaged Marilyn, a newly-widowed GP who lives (with her sister-in-law) and works in Kensington, and whom Mehmet first turns to for medical assistance when he’s injured in a fight, thereafter becoming her lover. And finally, Adrian, a wealthy, self-assured middle-aged businessman who buys his way into the Albanian’s affections with expensive dinners and weekend jaunts to his friends’ country retreats and whom Mehmet believes can secure favours from his friends at the Home Office, not to mention provide financial and legal assistance with the immigration authorities when they eventually come knocking.

Twenty years on, reading the novel in light of both Brexit and Britain’s increasingly draconian asylum laws, this aspect of the story has only become more relevant. But even at the time, King wasn’t pulling any punches. One might not go as far as to call The Nick of Time an overtly political book, but it subtly demonstrates how broader social and economic policies that dehumanize and demonize various vulnerable groups trickle down through society, leaching their poison into one-on-one relationships between individuals.

This is neatly signposted from the novel’s opening page when King momentarily accesses the mind of a driver who’s been forced to standstill because of Meg’s wheelchair’s mishap. The man waits, “turning his head from side to side, an expression of exasperation on his face, as he had deliberately avoided looking at this wretched lump of a woman who did not seem to know how to get her wheelchair to work. Oh, for Christ’s sake! Couldn’t that biddy who had begun to cross the road herself give the poor creature a hand? These days there was no solidarity between people, it was a case of everyone for himself.”

As the story progresses, we see just how pervasive—and how damaging—this attitude of “everyone for himself” is. And just to be absolutely clear, Mehmet is not the only victim here, nor is he a blameless figure of pity. He’s as capable of genuine acts of kindness, generosity and empathy as he is of being selfish, cruel and ruthless. In fact, it’s testament to King’s talents that despite being privy to Mehmet’s lies, double-crossing and increasingly combative and underhand actions, we too can’t help but fall for his charms, albeit not quite so heavily as poor Meg or Marilyn.

The Nick of Time is a novel that deals in murky morals, bad behaviour and troubled people. King doesn’t divide his characters into bad and good; like real people, they’re confused and confusing. Sometimes they’re thinking of others; often only of themselves. And who can blame them? More often than not, no one else has their back.

“[M]ine is an attitude of profound, if resigned, pessimism about the world,” King explained in the early 1970s, defending himself against readers and critics who hailed his work as “depressing” and who asked him why he couldn’t just write about “nice […] normal” people. “I do not expect people to behave consistently well,” was his brutally honest reply, “and my observation is that few of them do.”

This worldview accounts for the strong seam of melancholy that runs through King’s work, and which, one could argue, reaches its apotheosis in The Nick of Time, since it’s a novel that spares none of its characters and offers them little absolution either. “But I should like to think that the tolerance and compassion that I genuinely feel are also reflected in my writing,” King added, and indeed, there is something deeply and movingly humane about both the empathy and the forbearance he clearly has for his cast of troubled souls, Mehmet in particular.

Any reader familiar with King’s own story and earlier work might find themselves also wondering whether, in this instance, King’s treatment of Mehmet owes something to what was an especially significant and formative experience in his real life. King’s fictional Albanian is cut from similar cloth as Antonio, the enigmatic Italian philosophy student who’s the object of the narrator’s unrequited desire in A Domestic Animal, and who in turn was based on Giorgio Balloni, a young Italian economist who lodged in King’s Brighton house in the late 1960s, and with whom King became “totally obsessed” as he admits in Yesterday Came Suddenly.

Antonio’s ultimate unattainability affords this earlier novel a haunting, mournful elegance—its virtuosity was recognised, incidentally, when it was shortlisted for the infamous “Lost Man Booker Prize” in 2010 (the one-off prize that honoured the books that, due to the date of the prize having been moved that year from April to November, missed out on the opportunity of being considered for the 1970 award)—whereas Mehmet’s ready availability (which is often considered in explicitly mercenary terms, especially when it comes to his relationship with Adrian) makes for grittier, less romantic reading. It wouldn’t be without precedent to assume that a novelist might become more elegiac and starry-eyed with age, but King firmly bucks any such trend with The Nick of Time.

_______________________________

‘TBR: The Booker Revisited’, is an editorial partnership between The Booker Prize Foundation and Lit Hub.

Visit the Booker Prizes’ website for more features, interviews and reading recommendations covering the hundreds of books that have been nominated for its annual awards. Sign up for the Booker Prizes Substack here.

Lucy Scholes

Lucy Scholes is a senior editor at McNally Editions, and writes for The Independent, The Times Literary Supplement, The Observer, BBC, The Guardian, and is a columnist for The Paris Review.