The Book That Began as an Acid-Fueled Speech at Woodstock

When Pete Townshend Whacked Abbie Hoffman Offstage

Abbie Hoffman had been hearing rumors about an upcoming rock concert on farmland a couple of hours north of New York City since late spring. He saw the event as “an opportunity to reach masses of young people in a setting where they felt part of something bigger,” but he feared that the promoters were going to use the counterculture to make a fortune for themselves. If that were allowed to happen, then no matter how good the music might be, the message would be one of greed, not enlightenment, a rip-off that would be bad for the Movement.

Abbie reached the organizer of the event, Michael Lang, and demanded $10,000, 200 free tickets, an area for tables offering political literature, and the right to leaflet the crowd. In return, Abbie offered to help deal with some of the problems that were going to arise, things the promoters weren’t prepared to handle, like large numbers of people on bad acid. At first, Lang refused. Then, to Abbie’s amazement, Lang said yes. Abbie got the money and immediately spent half of it on a press to print political leaflets on-site, to make sure issues would remain an essential part of the concert.

Lang had pulled together an amazing roster of musicians that included Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Santana, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Richie Havens, Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, The Who, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and many others. The promoters were expecting about 75,000 fans. Abbie felt there was a good chance the crowd would be much larger.

As Woodstock began, so did the rain, but people just kept coming. On Friday afternoon, people with nine-to-five jobs joined the rush. Nearly half a million people had showed up by Saturday despite the rain that had turned the entire area into mud. Abbie couldn’t have been happier. To him, the phenomenon of Woodstock held special meaning that no amount of adversity could alter: It meant the Yippie! myth of peace, love, and music bringing people together was becoming a reality. Abbie felt that his job was to keep the struggle—against injustice at home and war in Vietnam—a part of the celebration.

Near dawn on Saturday morning, Abbie, high on acid, decided, rightly, that the instant metropolis that had risen around the forty-acre field was ridiculously unprepared for medical emergencies. Although he had no authority to do so, he commandeered the press tent alongside the stage, threw out all the journalists there, and announced that it was now a hospital. By 7:00 a.m., Abbie was barking his orders through a bullhorn. He had even commandeered a helicopter and made arrangements for more doctors to be flown in. Abbie may have acted obnoxiously but showed nearly perfect judgment that morning, and without the field hospital Woodstock might have been remembered very differently than it is.

Woodstock Nation is a tract written to even the score by the guy who was thrown off the stage.

The music was scheduled to begin on Saturday afternoon and last through Sunday. The New York Port Authority had stopped selling bus tickets to the area. National Guard troops had been mobilized. There was a rumor that the concert had been declared a disaster area. But the music was incredible, and by Saturday night the concert organizers knew they had pulled it off. Between sets, as The Who was getting ready to go on, Abbie sat on the side of the stage talking with Lang about the possibility of devoting a percentage of any movie revenue to a bail fund—in his mind was the recent imprisonment in Michigan of activist John Sinclair for possession of one marijuana joint.

Suddenly, Abbie decided it was the right moment for him to make a speech; still high on the LSD, maybe mixed in with some speed, he walked up to the mike and started rapping—about Sinclair, about the war in Vietnam, and the war at home. He went on for twenty minutes or so, then someone turned off his microphone. Angry, Abbie kicked over the mike and walked off. Peter Townshend of The Who was walking on. He passed Abbie and whacked him with his guitar, pushing him off the stage.

“I deeply regret [kicking Abbie offstage]. Abbie at Woodstock really was correctly despairing. He was fucking right.”

Abbie wasn’t seen again that weekend. In the Woodstock movie you don’t see Abbie and you don’t see his hospital. He continued talking about Woodstock Nation, and he would continue to feel that this was the nation to which he belonged. But he was shattered by the rebuke he had suffered. It put the fear in him that maybe other people didn’t share his aspirations, didn’t always care about the same things he did. I think it was the first time he felt like the leader of a party of one.

Years later, Townshend would tell Rolling Stone: “I deeply regret [kicking Abbie offstage]. Abbie at Woodstock really was correctly despairing. He was fucking right. If I was given that opportunity again, I would stop the show [to let Abbie speak]. Because I don’t think Rock & Roll is that important. Then I did. The show had to go on.”

Back in the city, Abbie camped out in the Random House office of editor Christopher Cerf, son of publishing legend and Random House founder Bennett Cerf, and started filling yellow legal pads, writing longhand in a burst of manic energy. Random House had wanted a sequel to Revolution for the Hell of It. In Woodstock Nation, Abbie was able to give them the book they wanted by, in effect, finishing off the speech he had begun on the Woodstock stage, redefining the rock concert as a political event and counterculture symbol, and affirming in print what he had been prevented from affirming at the concert.

Dedicated to Lenny Bruce, the book is a breathless and random collection of essays, vignettes, poster-like images, and photographs whose most striking characteristic is that it obliterates the distinctions between politics and culture. He called it a “talk-rock album,” and the chapters are referred to as “song titles.” Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin are there, and so are Elvis Presley, Che Guevara, John Sinclair, and Norman Mailer. The politics of the book are pervasive, but nowhere as clear or as striking as in his other writings. The central theme is Abbie’s recent Woodstock experience, an understanding of which in many ways still eluded him. The passion of the book is intense and appears on every page. But the frenzied quality of the writing denies it the saving grace of Abbie’s other books, where underneath the zaniness you can feel the presence of an utterly clear mind and an uncluttered heart. For all its virtues, Woodstock Nation is a tract written to even the score by the guy who was thrown off the stage.

__________________________________

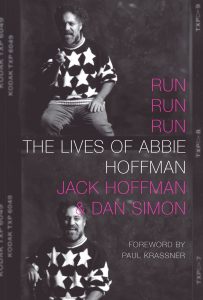

Excerpted from Run Run Run: The Lives of Abbie Hoffman by Jack Hoffman and Dan Simon, published by Seven Stories Press on January 14, 2020.

Jack Hoffman and Daniel Simon

Jack Hoffman, Abbie's only brother, was also his longtime manager, researcher, and confidant. A businessman, he lives in Framingham, Massachusetts. Daniel Simon is the founder and publisher of Seven Stories Press. He is the translator of Van Gogh: Self Portraits by Pascal Bonafoux. The two are the authors of Run Run Run: The Lives of Abbie Hoffman.