MARIBEL GARCÍA MEDINA

Besides David King and Samuel Prince, there was an older one, Mary Johannes, she was called, or still is, because she’s alive and things are going better for her than for us. They arrived in Punta Gotica one day in an old Ford truck with Camagüey plates. I remember them unloading their stuff. Too much furniture for someone moving into a neighborhood like this, I thought from the first.

*

YOHANDRIS CARLOS FERNÁNDEZ RAMÍREZ,

a.k.a. GUTS

I was playing soccer when they arrived. This can’t be good, I thought, because the girl riding in the truck’s cab was fanning herself and looking at the neighborhood as if they’d dropped her right at the doors to hell. “One more sucker in town,” I said out loud, and went back to doing my thing. The guys were just kids then; Cricket, the older one, already looked like a total nutjob. I can take that one, I’ll hack him down like a palm tree, I thought, because he was very tall. “Guts, he’s so tall he can’t scratch his own ass,” Nacho Fat-Lips said, and passed me the ball.

*

MARIBEL

I’ve lived here for years, but that doesn’t mean I’m tied down here. The thing is that this place, before the riffraff began moving in, was a rooming house for sailors. That was back in the time of the other government, and a nephew of President Machado himself lived in one of the rooms. He’d also met José Martí’s son, you know, that Ismaelillo—and actually, it seems that Martí wasn’t as famous then as he is now, when he shows up all over the place and you can’t even turn on the TV without hearing, “As the apostle of Cuban independence said,” and, well, it gets a little old. They say that Ismaelillo was in the business of renting out rooms, and one of his customers was this nephew of Machado’s, who owed him for about six months. He didn’t charge him because, on the day that he personally went to kick him out of the house, all of Martí’s works were there in a bookcase, cared for like they were made of gold, and Ismaelillo got sentimental and forgave Machado’s relative, who, now that I think of it, must have been his nephew by marriage, because no matter how cheap he was, a former president wouldn’t have his sister’s son renting one of these little rooms that get miserable as hell on a hot day, now would he? But back to the folks from Camagüey: when they got here, it had been three months since I’d broken up with Chago, and, well, I really had a thing for everything from the eastern part of the island, and when I heard they were from around there, I went to take a look at the move, specifically so that I could drop a few snide comments here and there to see if the new neighbor had it in her to hop over and say something to me, to show me up front what this family was really made of.

*

BERTA

I didn’t see them arrive, since I was at school. It was my mother who told me that old Castillo’s place had been taken over by a family with a girl who was more or less my age, but that she didn’t want us getting together right away. “First you have to get to know people,” she said. “That’s why things happen to you, you’re too trusting.” I told her it was fine, that I didn’t really want to meet anyone anyway, but after I changed out of my uniform, since I didn’t have anything else to do, I sat at the door to our house and looked over at the place that used to belong to Castillo, an old man who, as mean-spirited gossip had it, died of cirrhosis.

*

MARIBEL

All of it could have been avoided if they hadn’t drawn so much attention, but ever since they arrived, with their stuck-up faces and wearing that fancy gear, the people in the neighborhood fell all over themselves for them. “Did you meet the folks from Camagüey?” Lucy the gum seller asked me, taking over a little plate of sweet potato pudding to the girl, who, according to the mother, was in delicate health. I had seen that young girl and she seemed healthy as a horse, thin, with slanted eyes, a beautiful black girl, yes, but full of herself—now she lives in Italy, all the ones like her end up over there.

The truth is that we were innocent back then, even if our future was already wasted.That man from Camagüey ate, lived, and breathed Jesus Christ, always had Him at the tip of his tongue. The day of their arrival, he threw five pesos at the kids who were playing soccer so they would help him unload the stuff, and then he came over to greet us. He had a polite smile and a thin, strong, dry hand. “Blessings,” he said. “My name is Arturo and this is my wife, Carmen.” “Blessings,” echoed that Carmen, who was walking a few steps behind; you could tell she was too hot for a guy like him, in his 50s and pretty run-down, you could tell that wouldn’t end well. I was shocked when he introduced the kids, since they didn’t seem like they were hers. The three of them were tall, especially the older boy, David, he was a real beanpole and only 13 years old. The younger one, Prince, held out his elegant, slightly sweaty hand and looked at us with those same slanted eyes as his mother and his sister, and I thought, This one’s a fairy.

“Please, can you tell me where the Church of the Holy Sacrament is?” the guy asked.

“Church of the Holy Sacrament?” was the response. “There’s never been anything like that here.”

*

GUTS

Jelly, Barbarito, Lupe’s kid, named him, as soon as he saw him reading right in the middle of the day, as if there were no soccer to play, no girls to check out, no kite to fly, no gas to pass. He said to me, “Guts, if this guy isn’t a fairy, he knows where the pixie dust is,” especially since the kid was wearing some tight pants, a little too short, that were ugly as sin. “That’s the fashion in Camagüey,” Berta had to say, she was already defending him back then, saying he looked like Michael Jackson before he bleached his skin, that he was a beautiful black boy like none other in the neighborhood and that he was good enough to eat; “not like his brother, who you can tell is kind of loony.”

“That one’s queerer than a three-dollar bill,” Barbarito insisted. “You’ll see.”

*

ALAIN SILVA ACOSTA

The truth is that we were innocent back then, even if our future was already wasted. No one gets out of this neighborhood alive, someone had written on the side of a house, because the neighborhood was bad, really and truly bad. If you’re born black, you’re already screwed; imagine if, in addition, you have to live in the squalid rooming houses of a neighborhood like this; and I’m a university graduate, a psychologist, and even have a master’s in business administration, you’d think I wouldn’t be so fucked. But with a salary of four hundred pesos and no bonus in foreign currency, what can you possibly come up with? Nothing—Armageddon. I didn’t see them arrive; they called me when the younger one, Prince, split open Lupe’s kid Bárbaro’s head. He did it with a book, terrible, blood everywhere, and I said, “Somebody’s going to get it,” because that Lupe isn’t rational, she’s a fat black woman with arms that look like Muhammad Ali’s and a temper that, well, I don’t know what to compare it to, but to say it’s short would be an understatement. “Does his mother know yet?” I asked, while I cleaned up the kid’s wound.

“Not yet, she’s out, busting her ass.”

“When she finds out, she’s gonna make a lot of noise.”

“That Jelly is going to pay for this, I’ll make him suck my balls, goddammit, I’ll cut off his dick, shit, goddamn,” Barbarito said, his eyes tearing up, not looking like he could hurt anyone.

__________________________________

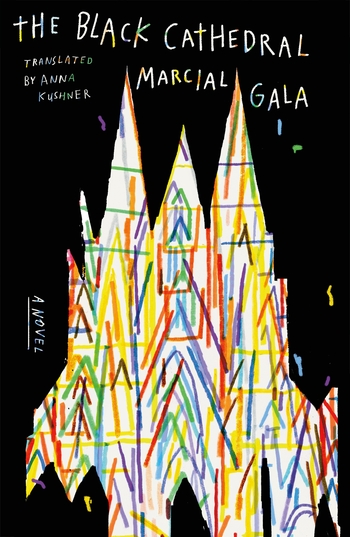

Excerpted from The Black Cathedral: A Novel by Marcial Gala. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux January 7th 2020. Copyright © 2012 by Marcial Gala. Translation copyright © 2020 by Anna Kushner. All rights reserved.