The Bizarre, True Story of the World’s Greatest Living Art Thief

Is Stealing a Work of Art Ever Excusable? One Master Thief Claims Yes

The world’s greatest living art thief is likely a 52-year-old Frenchman named Stéphane Breitwieser, who has stolen from some 200 museums, taking art worth an estimated total of $2 billion. While working on a book about him, I interviewed Breitwieser extensively, during which he discussed the details of dozens of his heists—and also expressed the brazen belief that his art crimes should be considered forgivable.

But only his crimes. Breitwieser said that he didn’t even like being called an art thief, because all other art thieves seemed to be nothing more than art-hating thugs. This includes the most accomplished ones, like the two men who robbed Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum on the night of St. Patrick’s Day, 1990. The Gardner thieves assaulted the pair of overnight guards, bound the guards’ eyes and mouths with duct tape, and handcuffed them to pipes in the basement.

Then the Gardner robbers yanked down a magnificent Rembrandt seascape, and one of the men stuck a knife in it. Breitwieser can hardly bring himself to imagine it—the blade ripping along the edge of the work, paint flakes spraying, canvas threads ripping, until the masterpiece, released from its stretcher and frame, curled up as if in death throes. The thieves, whose $500 million crime remains unsolved, then moved on to another Rembrandt and did it again. “They’re barbarians,” said Breitwieser.

Breitwieser, along with his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, who served as lookout on most of his thefts, never resorted to violence, or so much as the threat of violence. They stole from museums only during opening hours, using subtle diversionary tactics that permitted Breitwieser to make things disappear, magician-like, from walls or display cases, while carefully avoiding security cameras and alarm systems. The couple escaped by strolling out a museum’s front door, the artwork usually stashed beneath Breitwieser’s overcoat.

A picture frame, Breitwieser acknowledged, can make a painting cumbersome to steal. So what Breitwieser did after taking a work from the wall was turn the piece over and manipulate the clips or nails on the back until the frame was detached. He left the frame behind in the museum—empty frames were his calling card—and was mindful that the painting, now vulnerable as a newborn, had to be meticulously shielded from damage. Later, he’d reframe the work.

Also, Breitwieser emphasized, his sole motivation for stealing was aesthetic attraction. He only took pieces that stirred him emotionally, and he never sold anything he stole. Instead, he displayed everything in a pair of attic rooms where he and his girlfriend resided in his mother’s house in eastern France.

There, in the attic, Breitwieser could commune with the art in ways not possible in a museum—relaxed in a comfortable chair, able to run his fingertips over the pieces, quietly and peacefully immersed in beauty. He and Kleinklaus slept in a bed in the center of one of the rooms, surrounded by spectacular works. Breitwieser always kept the door to the attic rooms locked, monitored humidity and sunlight, and told his mother that the objects were flea-market finds.

Breitwieser argued that stealing the way he did—stealing for the love of art, in a refined and gentle manner—was an act of passion, deserving of hardly more punishment than a routine misdemeanor. Instead of an art thief, he preferred to be thought of as an art collector with a radical acquisition style. The criminal courts did not see it that way, and Breitwieser spent several years in prison. But I wondered how many other thieves were like Breitwieser. Who else stole for love?

I spoke with police inspectors and criminologists who specialize in art thefts; I combed through piles of art-crime reports. In the realm of fiction, sure—nearly every art thief in novels and movies is a sensitive connoisseur. But in real life, fewer than one in a thousand art thieves are driven by the desire to possess something beautiful. Actual art thieves only want the money they can get by fencing the works.

One of the rare exceptions was a physician in Philadelphia named Frank Waxman, married with two children, who stole dozens of items from art dealers in the 1970s and early 80s. Like Breitwieser, Waxman performed only daytime thefts, unarmed and well-dressed, hiding pieces under his jacket when gallery workers were distracted. An effective Waxman trick was to bring one of his young sons and ask an employee to keep watch on the child while he browsed.

Waxman was also not seeking money. He displayed the loot – including pieces by Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Pablo Picasso—in his apartment, the pieces spotlighted as if in a museum. He and his wife, who seems to have been under the impression that Waxman was spending an inheritance from his grandfather, hosted cocktail parties at their place, and this brazen lack of caution lead to Waxman’s arrest in 1982.

Breitwieser and Kleinklaus, meanwhile, never allowed anyone to enter their attic lair, including acquaintances, relatives, and repair people. If something broke, it remained that way or they fixed it themselves. They never invited friends over. When they weren’t stealing, the couple lived in discreet, almost monk-like seclusion.

Their mindset seemed similar to that of another art-crime exception, Rita and Jerry Alter. The Alters—unassuming, middle-aged public-school teachers, their two children grown—walked into the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson on the day after Thanksgiving 1985. Rita struck up a conversation with the only security guard on duty while Jerry ascended the stairs.

The weather was unseasonably cool, and Jerry kept on his coat. He soon returned and the Alters hastily left, fifteen minutes after they’d arrived. The guard, perplexed, checked the galleries and discovered an empty frame on the second floor where Willem de Kooning’s Woman-Ochre had hung. There were no surveillance cameras, but a police sketch of the couple was produced and the FBI worked the case.

Anticipating a speedy recovery, the Arizona museum preserved the blank frame on display. The value of the de Kooning soared past $100 million, and the frame remained vacant for 31 years. The Alters, it turned out, had driven four hours back to their ranch house in Cliff, New Mexico, population 293. They remounted the de Kooning in a faux-gold frame and placed it in their bedroom so that it could only be seen while the door was closed. Then they resumed their regular lives. Jerry passed away in 2011, but not until Rita died six years later was the painting recovered.

The Alters stole only one time. Breitwieser and Kleinklaus, starting in 1995, averaged one theft every 12 days for seven years. They often stole multiple pieces during a crime, and more than 300 works were eventually displayed in their attic. The couple is an anomaly among art stealers, but there does exist a group of criminals for whom long-term looting in service of artistic desire is common. In the taxonomy of sin, Breitwieser and Kleinklaus belong with the book thieves. Most people who steal large quantities of books are fanatic collectors, and there have been enough of these thieves that psychologists have grouped them into a specialized category. They’re called bibliomaniacs.

Alois Pichler, a Catholic priest from Germany stationed in Saint Petersburg, Russia, modified his winter jacket with a special inside sack and took more than 4,000 books from the Russian Imperial Library, from 1869 to 1871, before he was finally caught and exiled to Siberia for life.

Stephen Blumberg, from a wealthy Minnesota family, stole 20,000 books from libraries in the United States and Canada. Bookshelves filled every wall of his Victorian mansion, even in the bathrooms, and covered the windows. Blumberg was unmarried, lived off a trust fund, and read incessantly. He said he was trying to learn all that the world was forgetting. After he was betrayed by a confidant, the FBI hauled off 19 tons of books. Blumberg served four years in prison, was released in 1995, and promptly resumed book stealing.

Duncan Jevons, a turkey-farm laborer from Suffolk, England, stole 42,000 library books over 30 years, starting in the mid 1960s, stashing them a few at a time in his battered leather briefcase. He lived alone and had broad literary tastes, taking volumes on nearly every subject except sports. Books, said Jevons, never cause problems like people do. He was eventually nabbed by the police and spent eight months in jail.

Breitwiese’s favorite book thief is a fellow Frenchman, an engineering professor named Stanislas Gosse, who had a passion for religious tomes. Gosse stole a thousand volumes over two years from a securely locked library in a medieval monastery. The locks were changed three times during his binge, to no avail, for Gosse had learned, in the course of his constant reading, of a forgotten secret passage behind a hinged bookcase connecting to a back room of the adjacent hotel. He filled suitcases with books that felt to him abandoned, soiled with pigeon droppings, and entered and left the premises by blending in with tourist groups. Gosse cleaned the books and stored them in his apartment. He was arrested in 2002 after police hid a camera in the library, but just served probation.

Breitwieser, like many bibliomaniacs, claimed that his crimes were victimless. But Breitwieser deprived everyone else of the ability to experience the works he stole. He was a cancer on civil society; the victims were all of us. His thefts were in no way justifiable, though compared with run-of-the mill art thieves, Breitwieser’s crimes, like a great work of art, were at least aesthetically pleasing.

______________________________

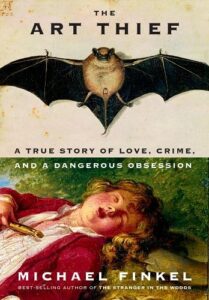

The Art Thief, by Michael Finkel, is available now from Knopf.

Michael Finkel

MICHAEL FINKEL is the best-selling author of The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit and True Story: Murder, Memoir, Mea Culpa. He lives in Salt Lake City, Utah.