The Biggest Influence on My Novel Is... McDonald's?

Ryan Chapman Worries It Is a Bad Idea to Compare

Your Writing to a Big Mac

If you ask about the influences on my novel, I will button my tweed blazer, pretend to blush, and name Martin Amis or Roberto Bolaño, maybe Calvin and Hobbes. In literary circles these replies get the right nods, and getting the right nods is the whole point of literary circles. But if I’m honest there’s a much deeper influence, a glacial aquifer of sustenance (if in fact that’s how glacial aquifers work): my father’s lifelong employment at McDonald’s. More than Money, more than 2666, those Golden Arches cast the largest shadow.

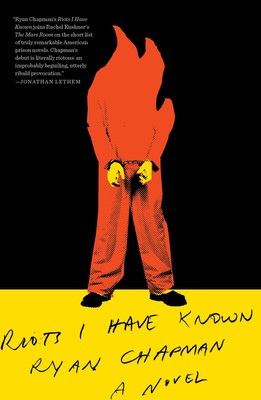

People who know my father assume his Sri Lankan heritage informed the protagonist of Riots I Have Known, my debut novel about a prison riot and the comic non-apology apology by its catalyst. This is true in a superficial sense. Both men are Sri Lankans of Dutch Burgher descent who immigrated to the US, worked incredibly hard, and embraced American culture with open arms. On the other hand, my narrator is serving multiple life sentences in an upstate New York correctional facility. My father is guilty of nothing worse than speeding tickets.

Timothy Chapman traded the heat of the subcontinent for the Minnesota tundra at 15 years old, in February of 1975. His mother had come four years earlier on a work visa to teach Montessori. His father, a high-ranking officer in the Sri Lankan military, found work at the now defunct department-store chain Montgomery Ward. Timothy was excited by America and bored by high school: the lax pace couldn’t compete with the Jesuits back in Colombo. He graduated at 16, enrolled at the local community college, and flipped burgers to pay tuition. Then McDonald’s promoted him. And promoted him again. And again.

These promotions took him from the drive-thru to Hamburger University, which is the actual name of the management training program. (No, they do not sell college-style sweatshirts sporting HAMBURGER across the chest. I’ve asked.) My father rose to Director of Worldwide Operations, based out of global HQ in Oak Brook, Illinois, and traveled to Japan, Singapore, Australia, and Brazil. He can tell you when the McRib is coming back, and to which regional markets. He can tell you which menu item is the most-ordered in every US location. (A Coke.)

All in all, his tenure spanned five decades. Did you just gasp? You’re probably younger than 50. These days white-collar longevity is the stuff of myth and bedside prayer.

McDonald’s prizes consistency and efficiency above all else. This guarantees your Egg McMuffin is delivered within 90 seconds and tastes the same every time, at every location. It’s why you never see idling employees; managers are fond of the line, “If you’ve got time to lean, you’ve got time to clean.” And it’s why employees clock in at the exact start of their shifts: at nine dollars an hour—the average cashier’s wage in NYC—an extra minute is fifteen cents on the payroll. Multiply that by hundreds of thousands of employees, it adds up.

Fans of Max Weber know the effects of these values on identity. I agree, or at least I remember nodding while reading Weber in college. But let’s sidestep the sociological critique. At heart the McDonald’s approach to life means efficiently packing as much into each day as possible.

This translated into peculiar behavior in adolescence. I vaulted stairs two at a time in the belief it expended less overall effort—a belief I clung to despite multiple debates with my physics teacher. (Stubbornness is another Chapman trait.) I obsessed over rounding hallway corners in the fewest steps, which sometimes led to a bruised shoulder from misjudging the angles. I thought this behavior was normal, in the way teenagers universalize individual experience.

Reinvention is as American as apple pie—which still costs just 99 cents at participating locations.

I also read with McDonald’s values, creating a training regimen of literature. This was in reaction to my absurdly competitive high school. (With 3,000 students, it was the largest in Minnesota.) How competitive? A single A-minus dropped you from the top 10 percent of your class. I had one friend who earned a 1600 on his SATs with zero prep, mostly to spite his brother’s score of 1520. I figured if I couldn’t outsmart my peers I could at least out-read them. Results varied; 15 was too early for Ulysses.

To my father’s credit, he never steered me toward law, medicine, or any of the other stereotypical aspirations of first-generation Americans. He was amused by my voracious literary appetite—it wasn’t a bookish household—and said I could do what I liked as long as I kept my grades up.

What I liked: writing fiction. It’s been my sole ambition as long as I can remember, save for a seventh-grade flirtation with rollercoaster design. During and after college I toiled on a first novel best described as a crap version of Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station. I wisely shelved it. A few years passed and I began work on Riots I Have Known.

The aforementioned narrator has unwittingly sparked a large-scale riot, with TV news crews circling the fences and a violent mob barreling toward his hideout in the prison’s computer lab. Riots is his attempted confession, framed as the final Editor’s Letter of the prison literary journal The Holding Pen. He’s determined to share his life story before intervention and dismemberment.

Hand on heart, I didn’t see the McDonald’s influence—which we could call Big Mac Style, but won’t—until a recent conversation with my editor. In the light-bulb moment I figuratively slapped my forehead and literally scratched my chin.

It’s all so obvious now. The mea culpa could be interrupted at any moment, so each sentence is packed with information and feeling, providing maximum value in the smallest novelistic unit. As for the narrator, he’s highly unreliable, possibly sociopathic, and most certainly a con artist: the literary equivalent of empty calories. The book itself is only 128 pages. It can be read in a single sitting, like a Big Mac value meal consumed a little too quickly, leaving a satisfying yet discomforting taste in the mouth.

I’m aware many people dislike Big Macs, and comparing my book to one might be unwise. A part of me wishes my father had immigrated with a library of foundational Sri Lankan literature. I would claim my novel as a small step forward in the national parade of unheard voices. We do have the great Michael Ondaatje, but he’s lived in Toronto for decades. And I’ve only met one Sri Lankan-American outside my family: Sunil Yapa, also a novelist. Go figure.

Yes, the McDonald’s influence looms largest. I believe it’s as my father would have wished. For all the narrator’s (sizable) faults, he endears, burnishing his myth and reinventing himself to the very end. As any immigrant will tell you, reinvention is as American as apple pie—which still costs just 99 cents at participating locations.

___________________________________________

Ryan Chapman’s Riots I Have Known is out May 2019 on Simon & Schuster.

Ryan Chapman

Ryan Chapman is the author of the novels The Audacity (Soho Press, 2024) and Riots I Have Known (Simon & Schuster, 2019). His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, The Sewanee Review, The Believer, and elsewhere. He teaches at Vassar College and the Sewanee School of Letters, and is a contributing editor to BOMB magazine. He lives in Kingston, New York.