The Best Sex I Ever Had Was (Also) a Narrative Structure

Helen Betya Rubinstein on Expectation, Eagerness, and Enjoyment

There’s something sexy about narrative structure. We’ve known this since before Robert Scholes wrote in 1979 that “The archetype of all fiction is the sexual act”—“the fundamental orgastic rhythm of tumescence and detumescence, of tension and resolution, of intensification to the point of climax and consummation.” We’ve known it since before 1863, when Freytag drew his triangle—since Aristotle’s Poetics, perhaps. Writing in 2019, Jane Alison got some attention by answering these men: “Well. This is not how I experience sex…”

Alison rightly accuses the classic dramatic arc of being “a little masculo-sexual,” and asks, “Why is this the form we should expect our stories to take?” For her, the question summons a series of alternatives to that dreaded triangle, shapes in the vein of John McPhee’s well-circulated images of his own essay structures. But when I read Alison’s galvanizing question, I heard echoes of Emily Nagoski’s Come As You Are, a popular guide to sex that is adamant in its refusal of prescription, masculo-sexual or not. Rather than dismiss the relevance of sex to our conversations about structure, I wondered: What if we turned toward sex—in its infinite variation—for advice about structure? Could a more expansive and inclusive conception of sex help us think more expansively and inclusively about structure?

Nagoski never defines or even really describes sex, but points to some qualities that help us know it: arousal, desire, release. There are no diagrams in her book, because as entertaining as it might be to use shapes to describe sex, such shapes fail to tell us what actually matters, which is not what the shape of sex (or a text) is, but what the shape does. Without considering what such shapes are meant to achieve, we can’t make informed choices; instead, we’re left to follow empty scripts.

Structure is the order of information: exposition, rising action, conflict, falling action, resolution, if you’re following Freytag’s triangle; introduction, primary reasoning, secondary reasoning, clincher, conclusion, if you’re writing a high school essay. Structure is also pattern: the way that Didion’s essays move between scene and reflection, not unlike the way a scholarly writer might move between evidence and analysis, say; or the way a poet or fiction writer weaves repetition—of a sound, a frustration, or a character’s behavior—through a text. We can’t talk about structure without also talking about content. And structure is fractal: it can be described at the level of the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, the book. It’s both “local and global,” in Peter Elbow’s words.

I should add, too, that when I think about structure, I’m genre-agnostic: as I see it, all time-based work—film, TV, music, the essay, the sentence, sex—has a beginning, middle, and end, and if it has a beginning, middle, and end, then we writers are asking the same questions: Where do I start? How do I decide? What comes next? How do I know?

What if we turned toward sex—in its infinite variation—for advice about structure? Could a more expansive and inclusive conception of sex help us think more expansively and inclusively about structure?

“Pleasure is the goal” of the choices we make about sex, Nagoski insists. Conceiving of this broadly—as we would for sex—the same might be said of a writer’s choices about prose. In an essay on Donald Barthelme’s “The School,” George Saunders ascribes the story’s power to a series of narrative “gas stations,” those “things that fling our little car forward” because of the delight and promise they hold. “A story can be thought of as a series of these little gas stations,” he writes. “The main point is to get the reader around the track; that is, to the end of the story.” But getting the reader around the track “is just an excuse for the real work of a story, which is to give the reader a series of pleasure-bursts.”

Pleasure-bursts? ?

Writing is seduction, in other words, an invitation for pleasure to occur. And what is pleasure, for a reader? As with sex, we all have different answers, of course. Outside of personality and experience, our answers depend on context, environment, and mood. Humor, beauty, encounters with surprising ideas, encounters with difficult ideas, access to experiences unlike one’s own, access to experiences like one’s own, a safe space to feel deeply, or a safe space to stop feeling so much—any of these qualities might offer pleasure to one reader or another, or to the same reader in different circumstances. As readers, we are each differently aroused.

Nagoski explains the sensation of being turned on in terms oddly resonant with Saunders’ model: “accelerator” and “brakes.” These are her nicknames for the Sexual Excitation System and Sexual Inhibition System at the core of a “dual-control model” of sex described in the 1990s. In a state of arousal, one’s accelerator is activated as one’s brakes are deactivated. But what leads us “around the track” to the end of the story—which need not be climactic, of course—isn’t acceleration alone, because if fulfillment comes too quickly, then desire will disappear. Desire is what carries us through the story of sex, or the structure of story, and Nagoski divides desire into three components: expectation, enjoyment, and eagerness.

I’ve replaced “sexually” with “narratively” in Nagoski’s explanation: “Something [narratively] relevant happens, and your brain goes, ‘Hey, that’s [narratively] relevant.’ That’s expecting. And if the context is right, your brain also goes, ‘Hey, that’s nice!’ That’s enjoying. And if the stimulus is nice enough, your brain goes, ‘Ooh, go get more of that!’ That’s eagerness.”

In textual terms:

Expectation: a learned sense of what will come next. Genre informs expectation—we have expectations of a novel, and we have other expectations of a memoir or a biographical tome; our expectations for a novel published by a big-five publisher differ from those for a novel from an experimental press. Genre is socially constructed, external to the text at hand (like gender, yes, and like different genres of sex), but patterns are established within a text as well, like the pattern in Barthelme’s “The School,” where many creatures die and a classroom of students begs their male teacher for a demonstration of sex, and voila, a story that reads like a long joke is proselytized by legions of straight white male writing instructors evermore. If we know a writer’s other work, that will shape our expectations of something new; if we know the content of the first chapter, or even the first pages we read on 4m4zon, that will shape our expectations of the rest.

Structure is also pattern: the way that Didion’s essays move between scene and reflection, not unlike the way a scholarly writer might move between evidence and analysis.

Enjoyment: the pleasures of the text, its rewards. We wouldn’t buy the books above if what we experienced of them didn’t already contain some pleasure, and the promise of more. Consider the many levels of pleasure we can experience as readers: the pleasures of language, of sensuality (rhyme, rhythm, sound, but also the look of printed text, and yes, the book’s smell); the pleasures of meaning (intellectual, emotional); the pleasures of a sparkling question or gutting emotion in that first paragraph. The pleasures of companionship (including the companionship of the narrating persona, or of the character whose observations help you see yourself, or see around yourself). Humor, surprise, play—etc. etc. etc.

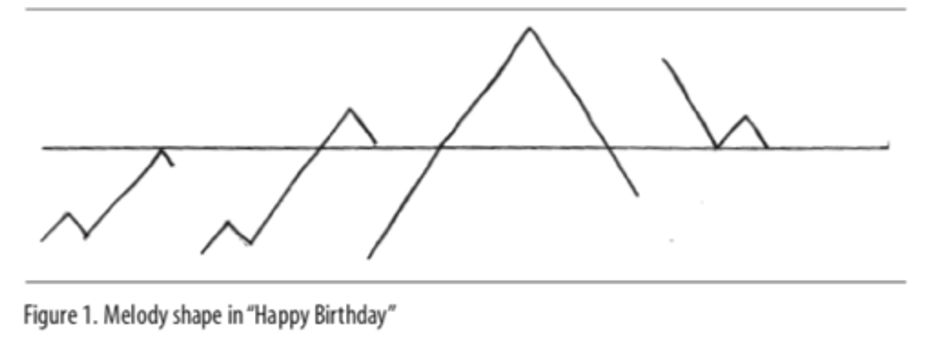

Eagerness: the combination of enjoyment and expectation that results in yearning and urgency. Consider Esther Perel’s descriptions of desire in Mating in Captivity, in which “a little bit of dissatisfaction […] allows wanting to emerge.” Or Peter Elbow’s essay “The Music of Form,” where he looks to music as a model for structuring prose: “Music works by setting up expectations that are sometimes fulfilled but often delayed or not satisfied,” he claims, sketching the shape of “Happy Birthday” to illustrate:

With my own students, I sometimes describe structure using what I call the Hansel-and-Gretel model: a series of breadcrumbs through the forest. I like this model because it applies to essays, too. We begin with one question, or hunger. An early answer to an early question builds a reader’s trust that other answers will come. And so the reader accepts the writer’s offered hand, as the two proceed into the woods. To return to Nagoski: Sex is an “incentive motivation system,” she says.

The prologue to Romeo and Juliet serves as a classic example. “A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life,” we’re told. This creates an implicit promise, an expectation: we know what’s going to happen. Contrary to what some beginning writers might think, knowing what’s around the bend doesn’t kill our curiosity—it creates it. But we probably wouldn’t read forward, or “accelerate,” if we didn’t also enjoy the prologue for its language, its complex humanity, its suggestion of high drama, or another of its pleasures. That enjoyment, plus expectation, creates eagerness in the form of curiosity. We press the gas, advance through the structure. We do the only thing a reader can do, when it comes to advancing a story: we turn the page.

Or take a more contemporary classic, Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl,” which is a joy to teach in part for its genrelessness, and because there is often a reader who, when asked to describe the text’s structure, will say it has no structure—it’s a single sentence, a block of text. Of course, that dense paragraph is already a structure, rich in pattern (“this is how…”) and in those deviations from pattern that create texture and hold our attention. I’m always intrigued by the rifts in the dominant voice—those italicized lines that occur about one-third of the way through and just before the end: how pleasurable is that first interruption (the protest and the relief), and how the text fulfills this reader’s desire to experience that form of pleasure again. “Girl” is not an obviously pleasurable text: its subject is female subjugation, in Kincaid’s specific Antigua. But if we look, we find the seeds of expectation, eagerness, and a host of sensual, linguistic, and subversive delights.

Genre informs expectation—we have expectations of a novel, and we have other expectations of a memoir or a biographical tome.

As readers, we might pay attention to how the time-based works we love incentivize our attention with implicit promises, and with the enjoyment, or “pleasure-bursts,” that build trust and make us eager for more. As writers, we might remember to ask how we want our structures to function—what we hope any given structure might do for a reader—whether the occasion calls for a splashy act of tantalization and teasing, or a gentler process of discovery.

I can see an argument that, without knowing our specific readers, we have only our scripts, those lists of shapes, to determine our structural choices. But if we rely on these scripts—no matter how many we have—we will always be writing for the same readers, and at this point, I think all we know who they are. We might do better to seek out new readers, the readers we want, whose partnership in story-making brings us pleasure, and lets us uncover new pleasures in text.

Helen Betya Rubinstein

Helen Betya Rubinstein's book Feels Like Trouble: Transgressive Takes on Teaching, Writing, and Publishing is forthcoming from the University of New Orleans Press. Other essays and fiction appear in The Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, and Jewish Currents, where she is a contributing writer. She currently teaches at The New School, and works one-on-one with other writers as a coach.