On my first day in my first prison, the Eye Specialist Hospital of Aleppo, Syria, the captors gave me a blindfold—a grime-stained scrap of fabric they called “the cloth.” Before every interrogation and during my twice-daily excursions through the hospital corridor to the bathroom, they made me tie it over my eyes.

I knew everything about that blindfold. It lay on the floor of the cell I was occupying then, next to a pee bottle, a water bottle, and some bits of bread crust I was saving up. It was an early springtime green. It felt soft in my fingers. It had been decorated with dozens of tiny violets. I became attached to this blindfold, perhaps because, in that world of al Qaeda prisons, it was my only possession.

This cloth stayed with me through many cellmates, sessions of torture, escape attempts, and transfers from one prison to the next. Sandals came and went, as did spoons and pee bottles. I wore the same pair of bloody sea-green hospital pants for half a year. Eventually, they vanished, too. I held on to the blindfold.

At first, I hated this object because it meant total helplessness for me and, for them, a deeper kind of control. But it was such a tattered, threadbare, throwaway scarf that, if I tied it right, it could be used like a veil. I could see, and they didn’t know I could see. Later, it occurred to me that it had probably once belonged to a woman (because what would a Jebhat al-Nusra warrior want with purple flowers?), that it might have been used in her kitchen or to keep her hair in place, and so I started to think of it as my connection to the world I had lost: women, civility, cooking. I needed to hold on to it for this reason. I clove-hitched it around my neck once. It was long enough, when rolled into a rope, to work as a noose. That scarf was my emergency escape route. I wanted it nearby in case it became clear that a quiet slouching into soft fabric, followed by deep sleep, would be preferable to whatever horror they meant to videotape, then send out to the world.

There came a time when this head scarf soaked up my blood. My hair was coming out in handfuls then, like a dying sort of seaweed. When I removed the head scarf, there was more hair to it than there was fabric. I used it as a bandage now and then. It absorbed the sorts of things bandages absorb.

Through the months, the scarf mopped up my sweat and wiped away graffiti I scratched into the walls, then erased in a panic when a guard warned that my defacing their prisons might bring on the car battery. It soaked up soup I had spilled on the floor. Sometimes, when I had spare food, I hid the food within the cloth.

The blindfold, I began to think, was a register. Its blood, pus, and hair were the outward, visible marks of an ordeal that was above all else a trial of the spirit.I had no pen during my first 18 months, and no way to tell myself what was happening to me. The blindfold, I began to think, was a register. Its blood, pus, and hair were the outward, visible marks of an ordeal that was above all else a trial of the spirit. And it had kept me safe. “Where’s the cloth?” they used to shout when they opened up the cell door. If I had it in my hand and was busy blindfolding myself, they could see I was complying with the prison rules. They didn’t hit me. So I brandished it at them like a talisman, wrapped it around my eyes, and then, in this state of compliance and fleeting safety, I walked out from my cell, into their world.

I could see. I watched them at prayer, at study, in their kitchens and their meeting rooms. I was an unobserved observer in their little Islamic state—so it felt to me—and my safety within it was because of the purple flowers I had tied around my head. Those flowers helped me see. The blindfold was my laissez-passer. It was the little patch of magic carpet on which I traveled.

Now and then, other prisoners needed it. Someone was about to be interrogated. Or led away to god knows where—a torture chamber, the trunk of a car, a grave. “Do you have a cloth?” a guard would ask, banging on my cell door. “I gave mine to Yassin yesterday,” I would lie, or I would sigh: “A cloth? No. By god, I have nothing.”

Over time, it began to seem to me that the captors meant to tamp down all my senses and that, as a consequence, the senses had woken up. About a year and a half into my ordeal, they decided to allow me a pen and paper. Soon, I found myself writing a story. When I began it, I didn’t know much about the plot of this story but I did know that my blindfold would be important in it. For me, that blindfold represented the power of my senses over their ambition to shut them down.

Now I think that in those first months in the eye hospital, they wanted total disorientation for me—and for the other 50-odd prisoners they kept in windowless cells in that basement. The blindfold was meant to detach me from everything I knew about the world, including my name, which, in those days, became Filth and sometimes Ass and other times Insect. Perhaps I did become a bit unmoored—but as this was happening, my senses were on high alert.

For instance, in a prison, you learn to know what’s going on by smelling the air. The prisons in Syria smell of charred wood, burning trash, people throwing up in their cells, and the floor-cleaning fluid with which they mop up the scenes of their crimes. In the evenings, they smell of the feasts the fighters make for themselves: roasted chicken, cardamom in the coffee, piles of steamy, fluffy rice. On Fridays, the day of prayer, they smell of shampoo. When there is torture, they reek of the patchouli oil the men in black put in their beards. Every time you smell the oil, you know those men are on their way into the cell block.

Of course, I also listened. In the blackness of a cell—or when they took charge of tying the blindfold and so cinched it down tight—my ability to make sense of sound was all I had. Over time, I began to think that the auditory faculty runs much deeper than we know, that footsteps and whispers proceed directly to the lizard part of one’s brain, and that sounds had helped me see just as my blindfold helped me see.

In some of the prisons you hear the interrogations in high fidelity, as if they’re happening in the cell next to yours. Sometimes they do happen there. As they’re flogging the guy next door, they will sometimes tell you to thrust your face to the floor or against the wall, and you might well pretend to have heard nothing at all, but you cannot keep yourself from knowing what’s going on then.

The blindfold was meant to detach me from everything I knew about the world, including my name, which, in those days, became Filth and sometimes Ass and other times Insect.Elsewhere, it’s the squawk of the commanders’ two-way radios that sinks into your consciousness, and the codes they use among themselves when they are discussing the next checkpoint to be attacked, or the fate of such and such a prisoner. Sometimes it’s the sound of a certain commander as he barks at his underlings that awakens your senses, and other times it’s the conviction in the fighters’ voices as they sing their anthems.

Under such circumstances, what news does your senses bring you? Once, after I had spent an evening with the car battery and a commander in one of their interrogation rooms, the commander came to me in my cell. I was by myself. It was much too dark in there for me to see his face. I could scarcely see my hands. But I recognized the outline of his head against the light from the open door. I listened to him breathing. He shone his flashlight in my face. “Prepare yourself,” he said, “little liar. Tomorrow will be worse.”

I can handle this, I told myself, but I was drifting away from planet Earth then, and I wanted to drift away. The next round of investigation, as they called their electricity treatments, it turned out, wasn’t better or worse, but afterward I lost track of time. During one of the nights that followed, in the darkness in my cell, I saw my mother at her kitchen table. She was alone and hunched over the Boston telephone book, as if she were scouring the pages for my phone number. Didn’t I have a phone number? Of course, yes. I’ve always had phone numbers. But which one? She couldn’t find the right one—and so scoured every page. Page after page, she scoured.

During a subsequent night, I found my mother in Vermont. In her driveway, leaning across the hood of her car, her head down. She tried to smile. “Mom,” I said, “I’m in Syria now. I’m in the prison here.”

We had a dialog then, a little like this:

Me: Things are bad here, Mom.

Her: I know they are. But this is absurd. Can’t you talk to them?

Me: No.

Her: Surely…

Me: The other thing is… The thing is that I’m not coming home.

Her: What? Don’t be ridiculous.

Me: I wish I could change it.

Her: What? Where did you say you were?

Now she didn’t say a word. Was she confused? She looked into the hood of her car. She spoke to me, but I couldn’t hear. I reached across the hood. I was about to touch her. But she was disintegrating. She kept fading away. I needed her to talk to me then. Maybe she would have come back. Probably she wanted to, I thought. But the call to prayer was coming then and I was too awake to see her.

Once during my daydreams, I saw the last town in which I had been alive and free, a minor revolutionary capital called Binnish. The American journalist James Foley, I learned much later, was being kidnapped in an internet café in this village more or less at the hour in which I was seeing it in my imagination. ISIS beheaded him, of course. One night, I had a dialog—inside my cell—with the sweet-voiced shopkeeper I had met here. He had changed some Turkish liras for me. He had given me a paper napkin filled with baklava. Inside my cell, our conversation went like this:

Me: You said that if I needed anything in the world—anything at all—I should come to you.

Shopkeeper: Yes.

Me: I’m coming to you now. I need you.

Shopkeeper: But it’s too late. They have you.

Me: But surely you can call for help?

Shopkeeper: You came too far, into a country you never understood, that happens to be under the sway of an unopposable kind of faith.

Me: I see.

A funny thing about the al Qaeda prison system is that this feeling of looking down over your earlier life—over life on planet Earth, among living beings—never quite goes away. It can last for years. Sometimes, in your cell, you feel yourself gazing from an impossible height.

A funny thing about the al Qaeda prison system is that this feeling of looking down over your earlier life—over life on planet Earth, among living beings—never quite goes away.If you keep watching and keep a record of what you’ve seen, I think it’s possible that your sense of hearing, and the sense of sight that comes from being in a blindfold some of the time and in the pitch black much of the rest of the time, might allow you to see the society around you more deeply than those who can look on things openly, without restriction. Now I know that the captors sometimes collaborated in my efforts to see, and wanted me to see. At the time, I hadn’t the vaguest notion of what they were trying to do, and their efforts to make me see simply terrified me.

Neither the al Qaeda commanders nor the ISIS commanders with whom I sometimes shared a cell ever forced me to look at anything specific, but I’m sure they did want me, their American invader–enemy, to reckon with the spirit of the times in Syria. They controlled the oil, cities, landscapes, Palmyra. Could I not see how powerful they had become? Did I know this, really, in my soul? They must have felt I did not know.

There were times when they led me from the cell in my blindfold, brought me to the room at the end of the corridor, then had me lie face-first, in my blindfold, on a cement floor. They locked down my hands and legs into a medieval device—an iron cloverleaf sort of thing I felt but never quite saw—behind my back. When they had me lying on the floor with my feet and hands locked in the air in iron loops—I rocked on my stomach like a bloody sort of hobbyhorse—they ripped off my blindfold. They seized my hair by the roots. They thrust their faces into mine. “We want you to see us,” an interrogator told me in one such moment. He introduced himself. He introduced his friends. “We are from the al Qaeda organization,” he said. At the time, it seemed to me that the interrogator didn’t care what I looked at since he knew I would soon be dead. Now, however, I think that he seized my hair by the roots because he thought I was inclined to explain away or deny or, anyway, fail to reckon with the might of their Islamic state. He wasn’t going to allow me that luxury. He was going to make me see. Events like this happened more than once. Why would they have gone to such trouble if they weren’t trying to make me see?

The interrogators would give me their noms de guerre then—always absurd names, pulled from the pages of Islamic history, or dreamed up in order to suggest that the bearer was a sort of emissary from an Islamic state-of-the-future—the Emirate of Tunis, the Emirate of Canada. Sometimes they would pull down the scarves they had tied around their own faces. “Look us in the eyes!” they would say. “We are from the al Qaeda organization. Do you know who we are now?”

My instinct was to pretend I couldn’t understand—or see or know. For two years, whenever I felt I was going to see something I did not want to see I put my head in my hands. I stuffed my thumbs into my ears. But you cannot go on like this forever. Eventually a prisoner will know much more than he’s supposed to know.

Over time, I came to feel that seeing an Islamic state from underground—as most of my cells were underground—presents advantages the people walking about in the sunlight, on the surface of the earth, do not have. In an Islamic state, citizens can easily get themselves in trouble for looking too much or remembering too well. A proper citizen in an Islamic state should devote himself to prayer. Making money is okay. Looking after one’s family is fine. Keeping a private record of public life—as, for instance, spies do—is not. When people are caught up in the hurly-burly of everyday life, they often forget to look around them. In a war zone, death looms. Here, people are busy acquiring bits of food and fuel for the evening tea. If they have energy left over, they involve themselves in quarrels, love affairs, resentments, schemes, dreamy projects—and of course they stare at screens.

My feeling that I was about to die allowed me to see. In a prison cell, at the very end of your allotment of days, you are in a little eagles’ nest, a thousand feet above the surface of the earth. You can see everything. Why do the living struggle and sweat, you wonder, when all they really need to do is to live?

__________________________________

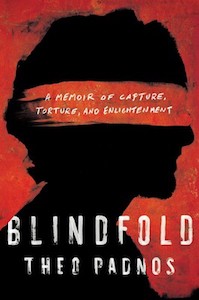

Excerpted from Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment by Theo Padnos. Copyright © 2021 by Theo Padnos. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.