The Beauty of Artistic Correspondence Through Collage: Ray Johnson and William S. Wilson

Elizabeth Zuba on the Friendship Between an Artist and a Writer

Paul Valéry once described poetry as “abrupt returns of the fruit to the wild state.” That description can also be applied to artist Ray Johnson—both the man and art. One of the most quietly consequential figures in American contemporary art, Johnson’s visionary perception and extraordinary faculty resulted in an immense body of work that spans collage, correspondence, performance, painting, sculpture and book arts.

Johnson’s poetic syllabary parses no difference between text and image, and his lyric is hewed from peripheral correlation and permutation; the result is breath-taking collisions that approximate the wilds of human experience.

“Wild” also perfectly captures Johnson’s puckish temperament and exacting mind. Stories of his singular attention and lightspeed wit are legendary. Keeping a pace with Johnson’s protean lens on the world was a feat reserved for only a few very close and similarly natured friends. The writer William S. (Bill) Wilson was one. Talking with or about Johnson required the “intimacy of immediacy,” as Wilson described it—the spontaneous, the indeterminate, the poetic and itinerant—characteristics Wilson possessed in spades.

Throughout their lifelong friendship, Johnson and Wilson challenged and enriched one another’s work. Frog Pond Splash, newly out from Siglio Press, briefly suspends and magnifies that relationship as well as provides an intimate portrait of Johnson that only Wilson could render.

Texts by Wilson and collage works by Johnson assemble juxtapositions and counterparts that do not explicate or illustrate; rather, they form a loose collage-like letter of works and writings that invite the reader to put the pieces together, to respond, and to add and return to the way both men required of their correspondents and each other.

*

In the passages below, Wilson reflects on his relationship with Johnson and Johnson’s work.

Ray Johnson. (Untitled (Moticos with Greek Statue and Swimmer), c. 1954–60. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

Ray Johnson. (Untitled (Moticos with Greek Statue and Swimmer), c. 1954–60. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

Ever since a childhood scarred by a severe deficiency in speech, I had wanted what I said to be understood as I intended it. But as with graffiti Ray pointed to on walls when we walked across Manhattan, and the scribbles I watched Cy Twombly penciling on paper he would then throw into the fireplace in his loft, themes included verbal non-comprehension and visual illegibility. There were no rules for and few clues to the difference between what was supposed to be read and what was to be illegible, and if illegible, the more visually available because of its opacity. . . .

Gutters and piles of trash in Chinatown were a source of scraps of paper which looked improbable to us, as we looked from the assumptions of our world toward the assumptions of the world which was alien and opaque to us. I was used to a transparency, as when reading through words on a surface toward meanings which were elsewhere in a kind of interior spaciousness. Words were supposed to be used in mediations with meanings.

Yet often with Ray, one couldn’t follow any verbal meanings away from the visual surface. Words held to a surface, and those perplexed surfaces were not only opaque, they were likely to be scratched to call attention to surface as surface. Words as Ray wrote them or drew them were difficult to read in the sense that it was impossible to know with certainty in which direction they were pointing.

A word was the more a material word for its illegibility, or for its freight of more references than it could be relieved of. A teacher at Yale University once quoted the motto of a house paint company: “Save the surface and you save everything.” Ray’s motto could have been, “Scratch the surface and you save the immediacies.”

—From “With Ray: The Art of Friendship.” Black Mountain College Dossiers No.4: Ray Johnson. North Carolina: Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, 1997.

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Red Profile), 1979. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Red Profile), 1979. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

Ray took a piece from the whole and showed something else existed in that piece besides what had been obvious when it was part of a whole. He would pay to watch a complete movie because the singer Connie Francis performed a part which, in the language of the day, was described as that of a “female mailman.” He took me to see a pornographic film featuring “Big Bill.”

When I complained afterwards about the lack of plot, Ray said: “Oh, Bill, you’re such a romantic.” Anything that attracted his attention could be itself, but also it could be used to point to something besides itself—hence in a sense it was freed from the seriousness of its selfhood . . . He wrote that Marianne Moore’s hat “is a manta ray. It is flat black.”

Later he adds: “I once thought of painting my flat black.” While “flat black” immediately suggests a matte, non-glossy paint surface, a flat is an apartment, so he had also thought of painting his apartment black. “Flat” can also be that which is flat or has been flattened, with suggestions of dullness or flavorlessness. The rhythm in some of Ray’s thinking is like breathing out and breathing in: he takes the air out of something, flattening it, and then he pumped it up again according to his own rules and desires.

–From “With Ray: The Art of Friendship.”

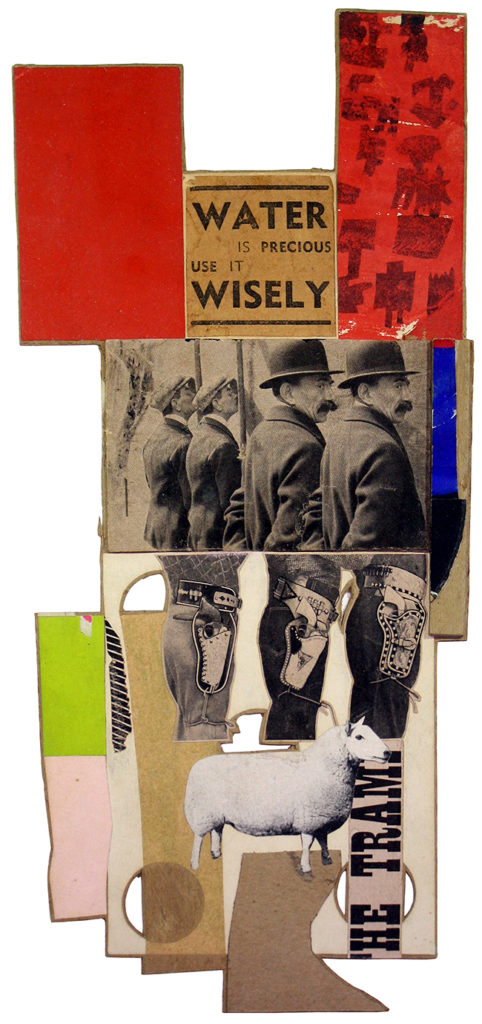

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Water is Precious), 1956. Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of The William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Water is Precious), 1956. Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of The William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson

One possible effect was that an ordinary event became a poem, because it became an event of significant images which were in the process of cohering into a whole. The process could be incomplete, even incompletable, yet open to additional images which added complexity and scope.

Ray, who often postponed questions of decisive completeness, rarely rounded off an experience. He usually ended events abruptly, at the edge of nothingness. Ray and I sometimes sat with Jimmy Waring as he sewed costumes with his sewing machine, adding decorations with needle and thread. He sewed seams and sequins in a dark room, under one bright light.

Separate parts of an event could go together like the parts of one of Jimmy Waring’s costumes, the variations among the methods of seaming which could be models for the seams of other events.

—From Untitled email. Received by Alanna Phelan and Frances Beatty, c. fall 2008-spring 2009.

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Holly Solomon with Duchamp and Flop Art), 1975−83−88. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Holly Solomon with Duchamp and Flop Art), 1975−83−88. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

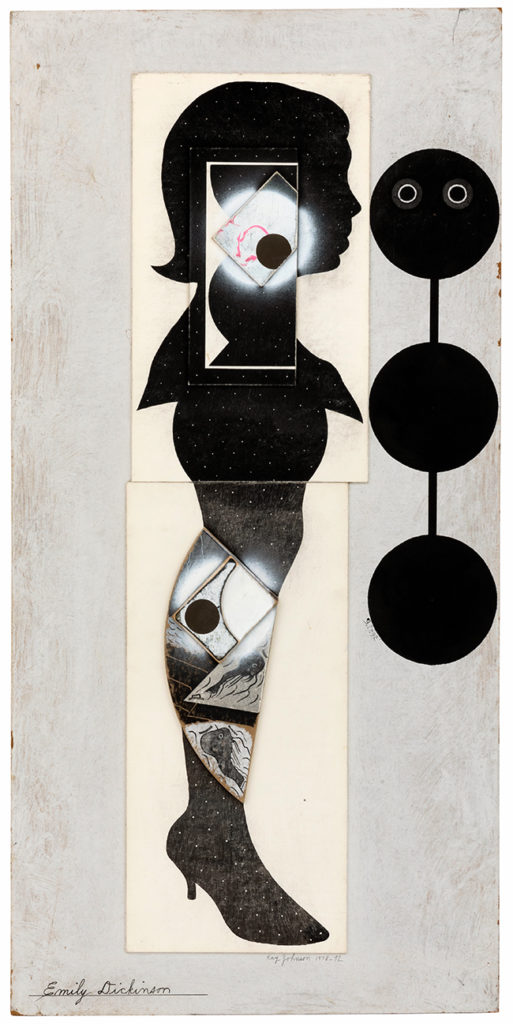

The first principle of Ray’s art is that anything isolated is beautiful, albeit opaque. The second principle is that meaning awakens in that isolated beautiful thing when it is juxtaposed to something like it (counterparts, like rhymes, for the romantic; counterpoints, like puns, for the ironic).

Ray said, “I deal in invisibilities and anonymities.” He said, “Andy Warhol says my snakes aren’t snakes—they’re worms because they aren’t lifesize. But some of my snakes are imaginary and inarticulate snakes, and what is lifesize about inarticulateness?” (4)

—From the introduction (dust jacket), The Paper Snake by Ray Johnson. New York: Something Else Press, 1965.

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Emily Dickinson), 1978–92. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

Ray Johnson. Untitled (Emily Dickinson), 1978–92. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

__________________________________

Frog Pond Splash: Collages by Ray Johnson with Texts by William S. Wilson, edited by Elizabeth Zuba, is now available from Siglio Press.

Elizabeth Zuba

Editor of Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954-1994 (Siglio Press) and Ray Johnson’s Art World (Feigen & Co.), Elizabeth Zuba has translated or edited over ten books of artists’ writings, including several by Marcel Broodthaers—Pense-Bête (Granary Books), 10,000 Francs Reward (Printed Matter), While reading the Lorelei (for the MoMA retrospective), Marcel Broodthaers: My Ogre Book Shadow Theater Midnight (Siglio Press)—as well as works by Nicolás Paris, Anouck Durand, and writings by Duchamp, Picabia, Satie, and other contributors to Dada magazine The Blind Man (Ugly Duckling Presse). Elizabeth is also the author of two books of poetry.