The Beautiful Impossibility of the World’s Largest Pearl

Bill François on the Natural Treasures of the Oyster

Seafood has one thing in common with cilantro, strong cheeses, and licorice-flavored tea: it tends to divide people. Although no one is really born with a love of oysters, there is a clear distinction, past a certain age, between those who sincerely love them, those who pretend to love them but mask the taste with vinegar, and those who openly despise them.

Among the true oyster-lovers, only a select few actually know how to properly open them without falling back on often dangerous tricks touted in countless online tutorials.

But whether or not you appreciate the taste, opening an oyster is like opening a book. You are presented with a drop of seawater enclosed in the mille-feuille of the shell, a pearly treasure safe under a rocky crust that resists and refuses to open. An oyster is full of underwater rumors and oceanic stories that, sealed inside, are not often shared.

While the gourmet pries open these shells and slurps down their contents, let’s wait for the oyster to calmly open up and release a few of its secrets.

Even on the outside the oyster shell is a material unlike any other. The mother-of-pearl, or nacre, from which it’s made is a biomineral, a mineral produced by a living being. This alliance between the animal and mineral kingdoms gives it extraordinary properties. Mother-of-pearl is composed of 99 percent calcium carbonate, also known as chalk. But the oyster knows the secret art of transforming soft and crumbly chalk into tough and precious mother-of-pearl.

The oyster tirelessly produces mother-of-pearl not only in order to grow, but also to protect itself.

The remaining one percent of ingredients contained in mother-of-pearl is a secret recipe for a protein-based cement, which the oyster uses to transform the chalk. The technique is still a mystery, but we do know that the oyster adds certain mineral salts to the chalk, in order to turn it into tiny tablets of limestone crystals called aragonite, which measure about a dozen microns across. The oyster then glues these crystals together in an unknown process involving a protein named conchiolin. Glued together in this way, the crystals form a material three thousand times stronger than aragonite alone, and of course much stronger than pure chalk. Mother-of-pearl by itself has no color; its material is unpigmented.

But when sunlight falls on it, it reflects off of each tiny aragonite tablet. These tablets are so small and so regularly spaced that the reflected beams interfere with each other, breaking down the sunlight into clearly distinct colors, which in some shells produce beautiful rainbow-tinted iridescences. Opticians call these “structural colors,” meaning that the colorless material of mother-of-pearl, through its shape and structure, breaks down the light into colors without itself possessing any trace of pigment.

The oyster tirelessly produces mother-of-pearl not only in order to grow, but also to protect itself. If a grain of sand enters an oyster’s shell, it’s like a pebble in our own shoes—annoying, distracting, and before long, painful. That’s why the oyster starts turning the grain of sand over and over, while covering it with mother-of-pearl, in hopes of ejecting it or at least making it smoother. Little by little, mother-of-pearl is deposited on the grain of sand, rounding it into a pearl. All oysters produce pearls. Although it’s rare to find pearls in commercially sold oysters, it’s not entirely impossible, and when it comes to pearls, it doesn’t hurt to believe in miracles. Oysters know this well. To help you keep the faith, even in front of your next oyster platter, let’s listen to an oyster who opens up slightly and tells us the true modern tale of the world’s largest pearl.

This story unfolds somewhere in the distant, crystal-clear waters of the Philippines. In the coral reefs of those latitudes live the world’s largest mollusks, measuring more than a yard across. This is the bénitier, French for giant clam, but also for “holy water stoup,” the large vase used in Catholic churches to hold holy water. These mollusks take their French name from the role they played during the Renaissance, when explorers brought them back to Europe as vessels for holy water. Some still serve this purpose today in old European cathedrals.

One day a grain of sand wedged its way into the shell of a giant clam, somewhere in the bed of a coral reef in the Palawan area of the Philippines. All the giant clam’s efforts to expel the grain of sand were fruitless. The mollusk had no choice but to produce a pearl around it, and that pearl grew and grew until it took up nearly all the room inside the shell. Things took an unexpected turn when a great storm hammered down one evening in the early 2000s. A local fisherman out at sea was unable to return to shore because of the breakers surging over the barrier reef. Making up his mind to spend the night at sea, he dropped anchor in the shallows. When the storm died down the following morning, and it came time to weigh anchor, he realized the anchor’s fluke had gotten stuck under something and dove down to yank it free. To his surprise he discovered that the anchor was stuck inside an enormous clam containing an immense, coiled, pearly mass with strange circumvolutions.

This fisherman was very poor and very superstitious. He had no idea what the pearl was, but he believed it was a magical object. Back home he hid it under his bed. Every morning before he set out to fish, the fisherman would touch the pearl under his bed, convinced that it would bring him luck. Ten years went by. Sometimes the fishing was good, and sometimes the fishing was bad. With a sailor’s typical confidence in the supernatural, the fisherman remained convinced that the magical object was watching over him.

After ten years the Filipino fisherman decided to move house. His aunt, who worked at a tourist museum in the city, came over to help him load boxes. When she laid eyes on the pearl, she was quite amazed, and recommended that her nephew have it appraised by an expert.

The invention of the method for producing artificial pearls is itself a story worth its weight in mother-of-pearl.

The story doesn’t tell us whether money brings happiness. But the Filipino fisherman found himself the owner of the world’s largest pearl, weighing in at 75 pounds, for an estimated value of more than 20 million dollars. Perhaps he was right to believe it was magical.

For many centuries pearls were very rare objects in France. It was therefore the artificial pearl industry that supplied the finery for the most spectacular courts in Europe. These artificial pearls did not come from oysters, or even from the sea, but their story nevertheless originates with a fish—an unassuming freshwater fish, a kind of shiner found in the waters of the Seine in Paris and the Rhône in Lyon, the common bleak. The invention of the method for producing artificial pearls is itself a story worth its weight in mother-of-pearl.

The year was 1686, in the Paris region. A patenôtrier, or rosary bead maker, named Maître Jacquin was bemoaning the very trade that had made him his fortune, fake pearls jewelry. Like all his competitors of that time, Jacquin gave the glass pearls he manufactured a nacreous appearance by filling hollow glass spheres with a mixture of mercury and lead that was terrible for the health of his customers. He knew it only too well, and so did his customers, but nonetheless those fake pearls were flying off the shelves, and people were paying their weight in gold for them. With each passing day Jacquin sank deeper into despair.

And yet he ought to have been ecstatic. His son was about to marry the ravishing Ursule, daughter of a neighboring apothecary. But the moment Maître Jacquin had been dreading had arrived. Ursule had just entreated Maître Jacquin to make one of his poisonous pearl jewels for her wedding day.

Unable to bring himself to fulfill the request, he spent long hours pondering a solution. As he wandered one day along the banks of the Seine, the enameled gleam of a school of common bleak caught his eye.

The rosary bead maker had no way of knowing that the scales of those fish possessed the same microscopic tablet structure as mother-of-pearl, in arrays of cells known as iridophores, and hence gave off the exact same iridescence as pearls. But he had a hunch that the brilliant glimmer would have a similar effect. With the assistance of his future brother-in-law, the apothecary, he developed a procedure using ammonia to preserve the tiny scales of the common bleak and inject them into the fine bubbles of wax-filled glass. He dubbed this process essence d’Orient, Eastern spirit, and soon all the courts of Europe were lining up to purchase these iridescent but harmless faux pearls.

Since it took 20 thousand fish to produce 500 grams of essence d’Orient, the common bleak fishing industry provided a living for entire villages along the banks of the Seine, the Saône, and the Rhône for more than 200 years. The wheels of many watermills, originally built to crush the scales of the common bleak, still turn in many French villages.

______________________________________

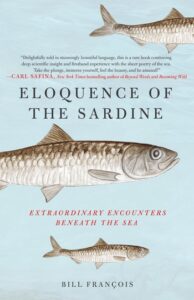

From Eloquence of the Sardine by Bill François. Copyright 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Bill François

Physicist and naturalist Bill François has always been fascinated by aquatic life. After he graduated from the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris with a PhD in fish hydrodynamics, his passion for writing and public speaking propelled him into the world of words. Now he blends the two universes to highlight the importance of protecting our oceans and share his love for the marine creatures.