The Beats' Holy Grail: The Letter That Inspired On the Road

On Neal Cassady's Rediscovered "Joan Anderson Letter"

Read Neal Cassady’s a never-before-published excerpt from the infamous “Joan Anderson Letter” at Alta Magazine.

![]()

The audience at the Beat Museum in San Francisco’s North Beach was small, and it fit a certain profile. About 20 people, mostly older—gray hair, jeans and open sandals—occupied a few rows of folding chairs in an upstairs gallery on a Saturday afternoon early this summer. At the front of the room, Cathy Cassady, 69, was narrating a PowerPoint presentation about her father, Neal. She was talking about his infamous “Joan Anderson Letter,” one of the legendary lost artifacts of American literature. Lost, that is, until it wasn’t.

It’s conventional wisdom that without Neal Cassady, there would not be a Beat Generation. He may not have been there at the inception point—the moment that Jack Kerouac, then a student at Columbia University, met Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs in 1942—but in every way that matters, he was the catalyst. “[F]ast, mad, confessional, completely serious,” Kerouac called Cassady in a 1968 Paris Review interview; he is remembered as the inspiration for Dean Moriarty, the central character in Kerouac’s 1957 breakthrough novel On the Road.

And yet, as true as this is, it is perhaps not true enough. Yes, Cassady was a muse of sorts. He appeared, in some form or another, in dozens of books: John Clellon Holmes’ Go, Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers and Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, as well as many works by Kerouac and Ginsberg. After the Beat days were over, he met Ken Kesey and drove the psychedelic school bus, Further, that carried the Merry Pranksters from San Francisco to New York. He was a road warrior, a nonstop talker, a speed freak who died in 1968 of exposure at age 41 in San Miguel Allende, Mexico. His life, or so legend tells us, was one of action, not thought.

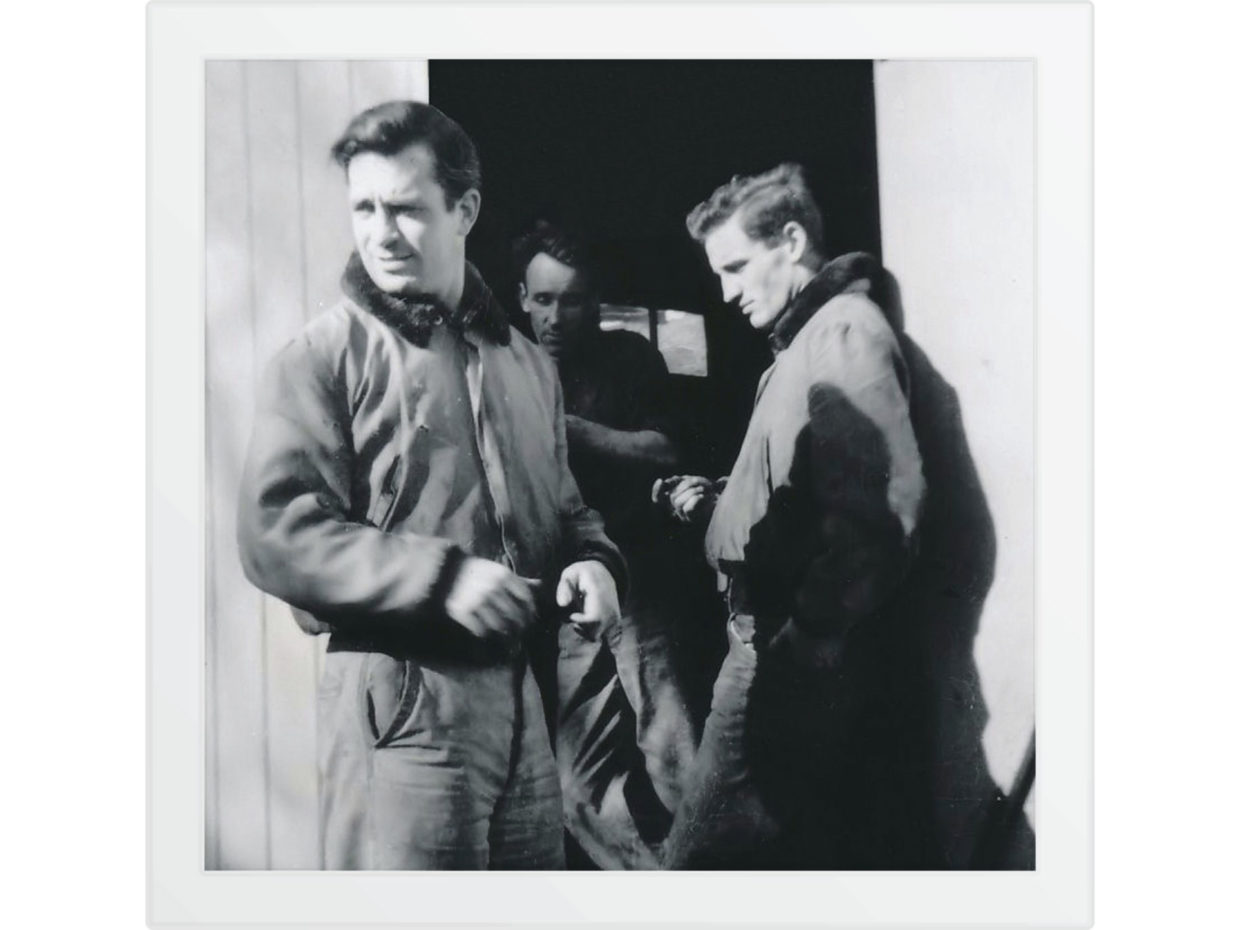

Cassady with his friend Jack Kerouac, whose On the Road was inspired by the “Joan Anderson Letter.” Courtesy of the Neal Cassady Estate.

Cassady with his friend Jack Kerouac, whose On the Road was inspired by the “Joan Anderson Letter.” Courtesy of the Neal Cassady Estate.

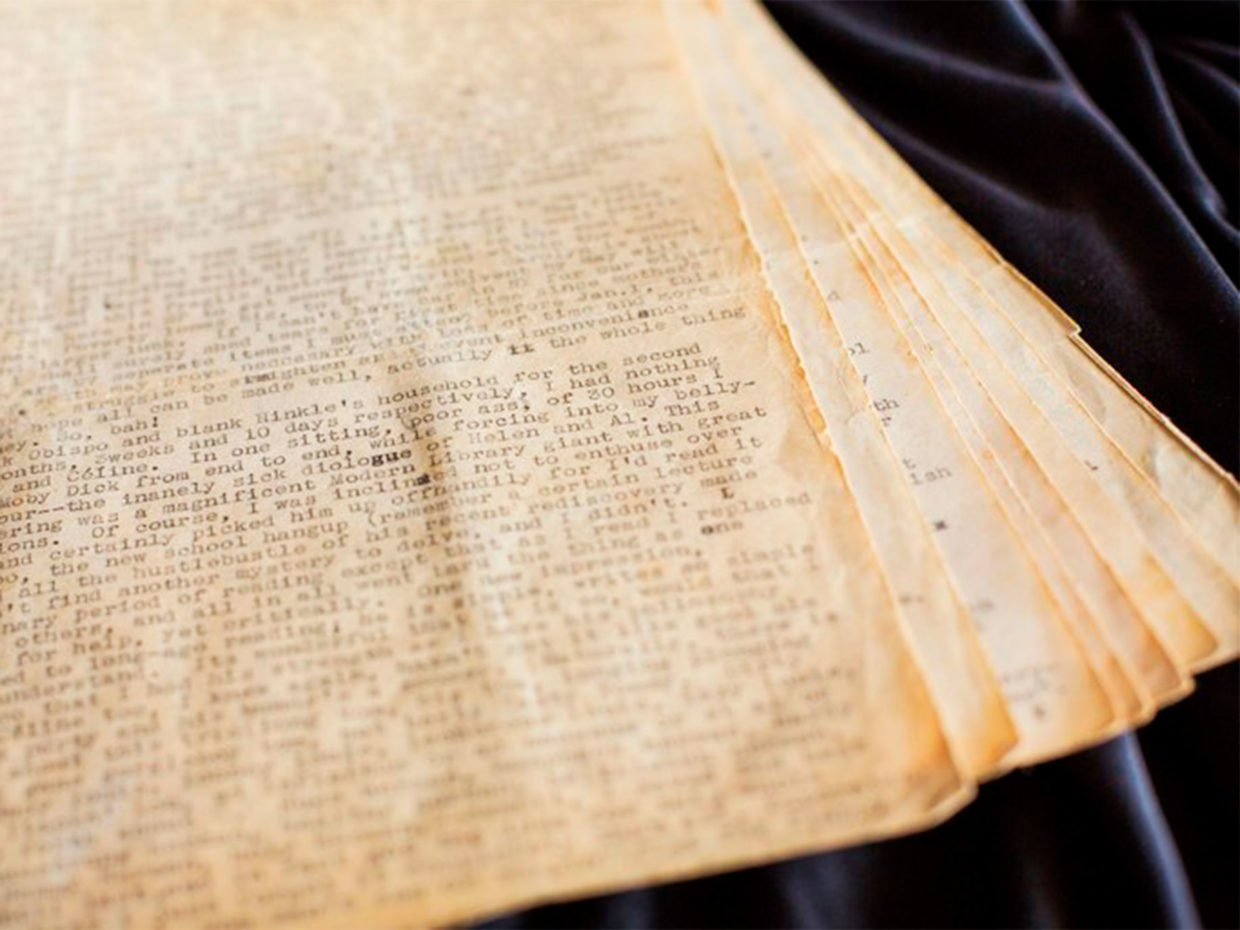

At the same time, Cassady also was a literary influence who pushed Kerouac toward spontaneous prose. The author had struggled to write On the Road for more than two years when he received a letter from Cassady that changed how he thought. “I got the flash from his style,” Kerouac told the Paris Review, recalling “the greatest piece of writing I ever saw”: thousands of words describing a star-crossed romance with a woman named Joan Anderson in 1940s Denver, typed single-spaced on both sides of several pages, with sporadic handwritten edits and interjections.

“Neal and I called it, for convenience, the Joan Anderson Letter,” Kerouac told the Paris Review, adding that the letter had ended up with “a guy called Gerd Stern who lived on a houseboat in Sausalito, California, in 1955, and this fellow lost the letter: overboard, I presume.”

REDISCOVERY

The Joan Anderson Letter, it turns out, was not missing. Rather, it was mislaid for 60 years. The letter was rediscovered in 2012 after the death of record producer Jack Spinosa; he got it from a colleague named Richard Emerson, who ran a small publishing company called Golden Goose Press. The story of its disappearance and emergence is a shaggy dog tale in its own right. “The holy grail of Beat literature,” Beat Museum founder Jerry Cimino calls it. But maybe there’s another way to think about this story, in terms of legacy.

Since the letter was found, after all, it has been a source of litigation and bad blood. “Some people,” emails Michael McQuate, a San Francisco collector who claims to have been present the night the letter was discovered, “have come up with the idea that this particular Letter is cursed.” Certainly, there have been claims and counterclaims—the first attempt to auction the letter (eventually, there were three of them) was canceled because of challenges from the Kerouac and Cassady estates.

Kerouac, in his way, foresaw the whole thing. “Now listen,” he said in 1968, “this letter would have been printed under Neal’s copyright, if we could find it, but as you know, it was my property as a letter to me.” Fifty years later, as part of her PowerPoint, Cassady’s oldest daughter showed a portrait by the artist Frank Ware in which the lines of her father’s face are etched in words from the letter, as if the language was literally rippling off his shoulders and his head.

This idea of Cassady as raw and elemental—a “holy barbarian,” to appropriate Lawrence Lipton’s phrase—is, for his family anyway, complex. “He wanted to be a responsible family man,” Cathy Cassady says, showing photos of her father in a suit for Easter and playing in the backyard. On the one hand, she’s not wrong; Cassady was, when present, an enthusiastic parent, and even as he careened back and forth by car across the country, he managed to hold a job with the Southern Pacific Railroad for 13 years.

Cassady, dressed in a suit for Easter, poses in the backyard in the 1950s with his children (from left) Jami, Cathy and John. Courtesy of the Cassady estate.

Cassady, dressed in a suit for Easter, poses in the backyard in the 1950s with his children (from left) Jami, Cathy and John. Courtesy of the Cassady estate.

On the other, he was a philanderer whose long-suffering wife, Carolyn, divorced him in 1963. In 1958, he offered cannabis to an undercover officer and wound up serving two years in San Quentin. “He was gone so often,” Cathy recalled over lunch before the Beat Museum event, “that we didn’t know he was in prison. It was just the way things were.” What she’s describing is the Cassady of the Joan Anderson Letter, a hustler on the prowl.

“I lolled on the hard onlooker’s bench,” he wrote, “looking for a mark. … Come evetide, I attached myself to the first available group touring the taverns—preferably in a car.” The letter is rife with sex and graphic language; the love story it purports to tell is really one of lust. “I haven’t been able to read it,” Cathy Cassady admitted, blushing as she sipped a glass of water. “His language, his sex addiction… I’m an old prude.” Her sister, Jami Cassady Ratto, offers a slightly different perspective: “He was a slave to his demons, he always said. The way he wrote was Dad.”

MANIC INSPIRATION

The letter rambled vividly and profanely through a crazy story about a few days in Denver in late 1945, beginning with Cassady meeting “a perfect beauty of such loveliness that I forgot everything else and immediately swore to forgo all my ordinary pursuits until I made her”: Joan Anderson. Its stream of consciousness is a rollercoaster ride through devotion, a breakup, a suicide attempt, a reunion, a reconciliation, an arrest, incarceration and, finally, abandonment. Appropriately, Cassady described the tale, mid-letter, as a “pricky tearjerker.”

This was what Kerouac admired most about the letter: the way Cassady’s personality exploded off the page. He had been looking for a strategy to open up his writing, and the immediacy of his friend’s account, full of digressions and moving back and forth in time, gave him an idea.

Within four months, Kerouac had scrapped his earlier efforts. He wrote a new version of “On the Road,” taking just three weeks. To avoid interruption, Kerouac taped together a 120-foot-long scroll of tracing paper and typed the novel as a continuous paragraph. “No pause to think of proper word but the infantile pileup of scatological buildup words till satisfaction is gained,” he later explained in his “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose.” This is what he learned from Cassady.

If the Joan Anderson Letter is not a great work in its own right—too self-indulgent, too juvenile, too sloppy in its execution—it is also impossible to read without seeing the seeds, at least, of what Kerouac would go on to achieve.

Such seeds account for the lingering interest in the Joan Anderson Letter, as well as its rediscovery: its life and afterlife, as it were. It took Spinosa’s daughter Jean two years to acknowledge she had found it, and then only after an auction was announced. This was the auction shut down by the Kerouac and Cassady estates, after the Beat Museum’s Cimino tipped them off. “As soon as it was public,” says Cimino, who had to sign a nondisclosure agreement to authenticate the document, “my first call was to Cathy Cassady. I said, ‘You need to be aware.’”

Then Cimino contacted Gerd Stern, now in his 80s, to tell him he’d been vindicated. Stern laughs about the situation now: “Only because no one had read the letter did people think it was an epic,” he sniffs by phone from his home in New Jersey. The response to its emergence, though, was something else again. Almost immediately, there were questions about rights, not to mention the timing of the announcement, which the Cassadys and others consider suspicious—“it’s my biggest beef with the whole thing,” Cimino laments—coming as it did after the 2013 death of Carolyn Cassady.

Jean Spinosa claims she was merely being careful. “If you find a lost Shakespeare folio,” she insists, “you don’t act hastily. My first thought was to protect it. What was the right thing to do?” Still, Jami Cassady Ratto notes, “Nobody told the family anything. We had to read in the paper that it was going to be auctioned.”

No one wants to say much about the legal machinations; they are, they insist, constrained. Regardless, it took 18 months for the parties to agree on a three-way split among Spinosa, the Cassadys and the Kerouac estate. In 2016, a second auction was announced by Christie’s, but it ended without a sale after no buyer was willing to bid the $400,000 minimum. Finally, in March 2017, the letter was sold at a third auction to Emory University for $206,250, which included $165,000 to be divided among the rights holders, and a $41,250 buyer’s premium. “In the end,” Cathy Cassady admits ruefully, “we didn’t come away with much.” (A full-length version of the letter can be obtained from Emory by researchers.)

Pages of Neal Cassady’s “Joan Anderson Letter.” Courtesy of Emory University.

Pages of Neal Cassady’s “Joan Anderson Letter.” Courtesy of Emory University.

THE LETTER’S LEGACY

As for what happens now, it’s something of an open question—as, to be sure, it ever was. The family would like to see the letter published in book form to showcase what they consider Cassady’s contribution to American literature. They also talk about a collection of the Kerouac-Cassady correspondence, although with both men’s letters already published, the market for such a project is unclear. Further complicating the landscape is the fact that a 5,000-word excerpt of the letter—until 2014, the only piece believed to remain in existence—was included in both Cassady’s Collected Letters and his book The First Third, a compendium of writings published by San Francisco’s City Lights Publishers in 1971.

“I received the manuscript in bits and pieces,” recalls Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who co-founded City Lights Bookstore in North Beach in 1953 and the press two years after that. “Over the years, I would get these manuscripts in the mail, and eventually we had enough to make the book.” There’s something fitting about that, the serendipitous nature of how the book was put together, not unlike the history of the letter itself. Indeed, suggests Elaine Katzenberger, City Lights’ current editorial director, perhaps the most appropriate way to publish the full letter might be in an expanded edition of “The First Third.” “No one,” Ferlinghetti says, “really considered him a writer. I don’t think he considered himself a writer. He just blurted it all out.”

In the end, this is the conundrum of both Cassady and his long-lost letter, and it comes back to the question of legacy. Cassady, Cimino says, was “damaged,” a street kid from Denver who became an American archetype because he “gave Jack a character.”

A similar dynamic affects how we think of Kerouac as well, since On the Road blurred the line between them in the popular imagination; “[People] kept mixing Jack up with Dean Moriarty,” John Clellon Holmes observed in the 1986 documentary “What Happened to Kerouac?” “They kept thinking he was like Dean Moriarty—in other words, Neal Cassady—and he wasn’t.” After six decades, they remain in some essential way connected, as represented by the mural on the outside wall of the Beat Museum, an oversized image of the two men together, adapted from a photograph taken in 1952 in San Francisco by Carolyn Cassady.

Of course, 1952 was a long time ago—a life-time, almost—as evidenced by the small group of spectators at the Beat Museum for Cathy Cassady’s talk about her family. What makes this material still relevant? For Cimino, it is the timelessness of the themes the Beats embodied: “rebellion, identity, and a desire to know who I am in this world.”

For Cathy and Jami Cassady, as well as their brother, John Allen, the reclamation is more personal; they want a piece of their father back. “He was fun, funny, always teaching,” Cathy says. Once he got out of jail, however, “he was on a downhill trajectory”—a recollection that her sister shares. “The last time I saw him,” Jami Cassady remembers, “it was January 1968 and he was hallucinating. I lay down with him, but I couldn’t do anything to help. A month later, he was gone.”

This is not the portrait of a family man, no matter his desire or intention, but of someone coming apart at the seams. “I wake to more horrors than Celine,” he writes in the Joan Anderson Letter, “not a vain statement for now I’ve passed thru just repetitious shudderings and nightmare twitches.” Seventeen years later, at his death, not so much had changed.

Yes, the letter helped to reshape Kerouac’s ideas on writing; without it, “On the Road” would have been a very different book. But it also framed Cassady as larger than life, which was both a blessing and a curse. “Legacy?” wonders Ferlinghetti. “His legacy is what Kerouac made of him. What else would his legacy be?”

This piece appears in the new issue of Alta Magazine.

David L. Ulin

David L. Ulin is a contributing editor to Literary Hub. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, his books include Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay.