German-born Italian photographer and publisher Inge Feltrinelli, described by some as “the queen of Italian publishing,” died on September 18 in Milan at the age of 87. She kicked off her career as a photojournalist by snapping a now-iconic portrait of Ernest Hemingway, Gregorio Fuentes, a marlin, and herself, and went on to photograph many great writers and artists, including Allen Ginsberg, Pablo Picasso, Greta Garbo, Gary Cooper, John F. Kennedy, Elia Kazan, and Marc Chagall.

In 1959, she married the publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who had been the first person to publish Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago, and by the late 1960s, she had effectively taken over the publishing house. She had an incredible eye for literary talent, and quickly steered Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore into the center of Italy’s leftist intellectual scene, publishing works by Isabel Allende, Gabriel García Márquez, Günther Grass, Doris Lessing, Amoz Oz, Nadine Gordimer, and many more.

We collected below the memories of some of those who knew and loved her.

Feature photo by Rachel Cobb.

![]()

Richard Ford, writer

I met Inge in the summer of 1988, implausibly in the lobby of the Hilton Hotel in Budapest. Implausibly, because it was probably the only time Inge ever found herself in a Hilton, anywhere. She was with her great friend Ledig Rowohlt, the brilliant, boisterous, diminutive Hamburg publisher of Faulkner, dressed in his regulation four-button serge suit, and smoking a considerable Montecristo. Inge was rather boisterous herself, “fabulously” dressed as usual in something bright and extremely orange. Together, they seemed like a still photograph of a pair of wealthy, Weimarish fun-seekers from the 1920s—naturally, they’d been drinking champagne. I, at that moment, had never heard of her Inge Feltrinelli. I was 44 and could not have more benighted. But when Inge was told my name—she was far across the lobby—she exclaimed to me and at me (there’s never been a better use of the word “exclaim”)… “Rich-ard Ford! I am your Italian publisher. Who are you?” There has never been a more propitious moment in any writer’s life.

Now that Inge has departed life and me—and now that I’m 74—there’s a selfish urge to say that a certain golden age has passed in world publishing. People who knew the greats; people who helped make the greats greater; publishers who read books, even wrote them; men and women who signed on to a writer’s career for the whole journey—not just till one book fails to earn out; publishers who knew their writers as friends, people for whom literature was a living force, not just a business… there’s a feeling this long moment of publishing giants has gone by.

But this view would be the last thing Inge would’ve conceded. Inge was a fantasy, a glory, a noisy, exuberant radiantly beloved, wily, intelligent, impassioned force in the lives of everyone who knew her or came across her. But she was also a supreme optimist. Publishers, whether they know it or not, are optimists—just like writers; it’s what we have in common. Inge believed in the promise of imaginative writing and therefore in the promise of publishing books. Namely that the world has an unexpressed need and that acts of imagination can approach that need. She believed that there will be a future in which books would and will be useful, and that publishing will continue being dedicated to that need. In other words, Inge believed that the only golden age is the one we’re living in right now; and it was her responsibility to burnish that patina a bit more brightly. She embodied and she reflected that brightness in her every breathing moment. I’m sorry for everyone who didn’t know her.

With Gunter Grasse.

With Gunter Grasse.

Judith Thurman, writer

A world without Inge? It is hard to fathom. She was the life force incarnate.

The voluptuous and intrepid beauty on the cover of Photographs, a collection of her work as a photojournalist, posing with Hemingway and a glistening marlin, did, of course, get older in the course of her nine decades—she would have been 88 in November. But she didn’t age, if you define aging as a progressive enfeeblement of spirit, the waning of desire, the failure of courage, the loss of a gift for abandon. We liked to reaffirm our membership in “The Bad Girls’ Club”—a sorority of female yea-sayers to pleasure and freedom—birth dates unimportant—but no one was badder than Inge.

She ran an empire, and several houses, where she dispensed her extravagant hospitality, and ruled a family that adored her. Inge was the empress of international publishing, and a patron of great books and writers, but also of newcomers, whose work she championed (I was once among them).

Her passions and her fashion sense were equally dramatic—she blazed into a room. And her loyalty was blazing, too. In literature, as in politics, Inge was, as the French say, a true engagée. Her engagement was immersive, contagious, and, at times, reckless because inhibition was alien to her, perhaps morally. But the one thing she never flaunted was her sorrows. There is a word for that coincidence of strength with stoicism: gallantry. Has a woman ever been more vivid than Inge? A more visceral embodiment of generosity?

And that, I think, is how we should mourn her: by turning up our own heat, and letting it warm others.

With Ernest Hemingway.

With Ernest Hemingway.

Lisa and Richard Howorth, booksellers

With the passing of Inge Feltrinelli, a large number of admirers and friends mourn, many of whom hail from the remotest parts of the planet, including Mississippi. I met Inge at a then-ABA party in 1987 hosted by the new regime at Atlantic Monthly Press, which included Morgan Entrekin and Gary Fisketjon. High times these were, with toasting and boasting over a medievally long dinner table, and one of the authors feted there was our friend Richard Ford, whose Rock Springs was near publication. (Years later I would become to Inge “Richard Two.”) After dinner I stepped out on the patio for fresh air and introduced myself to a smiling, gracious red-haired woman smoking a cigarette, wearing large glasses, stylishly and colorfully attired: Inge Feltrinelli.

Inge routinely attended ABA conventions at this time, when the foreign publishing community constituted a large presence. Lisa met her in Frankfurt a few years later, holding court with a group of writers and publishers, and witnessed the extent to which Inge presided over such affairs. Through the mutual friendships of the Fisketjons and Fords, we came to know and love Inge, her partner, the architect-philosopher, Tomas Maldonado, Inge’s son Carlo and his family. Carlo is the principal officer of the Feltrinelli publishing empire and its 100-plus bookstores. Carlo’s biography of his late father, Feltrinelli: A Story of Riches, Revolution, and Violent Death (Harcourt, 2001), is an amazing and tragic story, marvelously told.

We visited them all several times in Milan, where both the Feltrinelli family and business are centered. Inge lived on Via Andegari just around the corner from La Scala, and had a guest apartment nearby. We also met up with Inge in Venice, where she invited me to speak at the annual Italian bookseller school. One night we walked across the city to an opera at La Fenice, and I toted a box containing as needed either her walking shoes or dress shoes. On the way out of the theater, Inge hugged an old friend, introducing him to me. As he walked away, Inge nudged me, and said, “Gucci.” It took me a second to realize she referred not to his shoes, but the man. When we went to Harry’s Bar, the maître d’ greeted Inge as so many did, an old friend. We took home as gifts a couple of kits of Harry’s signature martini shot-glasses.

We stayed at their heavenly Villadeati, a drive south of Milan, and at their retreat in Mossna, Austria. Wherever Inge was, we were always treated to the unparalleled hospitality that so many writers, editors, booksellers, and publishers enjoyed.

Once, Inge came to Mississippi to visit us. She arrived shortly after our front hall roof had been “repaired” by an incompetent roofer. Came a rain storm, of course, and we set out buckets to catch the gushing leaks. When Inge walked through the door and saw the mess, she threw up her arms and shouted with a smile, “Ees Berlin… 1945!” We toured the Mississippi Delta and Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak. There Inge immediately found among the great writer’s library a copy of I Remember by Boris Pasternak, whose Doctor Zhivago became the foundational publication of Feltrinelli in 1957, after Inge’s husband, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, magically finagled worldwide publication rights.

Inge had a way of, um, elevating the status—and feelings—of everyone around her. Once, on a visit to the continent, not long after I’d been appointed to the Tennessee Valley Authority board by President Obama, whom Inge was wild for, everywhere we went in Milan she heralded me—not at all correctly—by saying, “He is of the family of Faulkner and a friend of Obama!”

Our younger daughter, Bebe, moved to Milan for a post-gap year or two to work for the Feltrinellis. Inge, at such ease with everyone, especially young people (she doted on her grandchildren), took her under her wing, ushering her about the city or sometimes as her substitute to wonderful parties, supervising her wardrobe, and just hanging out.

If here it seems that being with Inge Feltrinelli was like being in the movies, that is somewhat true. The scenery was always glamourous and the stories splendid, with plenty of laughter, though the conversation was generally serious, about literature or politics. But the movies don’t give you friendship and love, or endless coupes of her signature pink champagne, with which we’ll be toasting… “To Inge!”

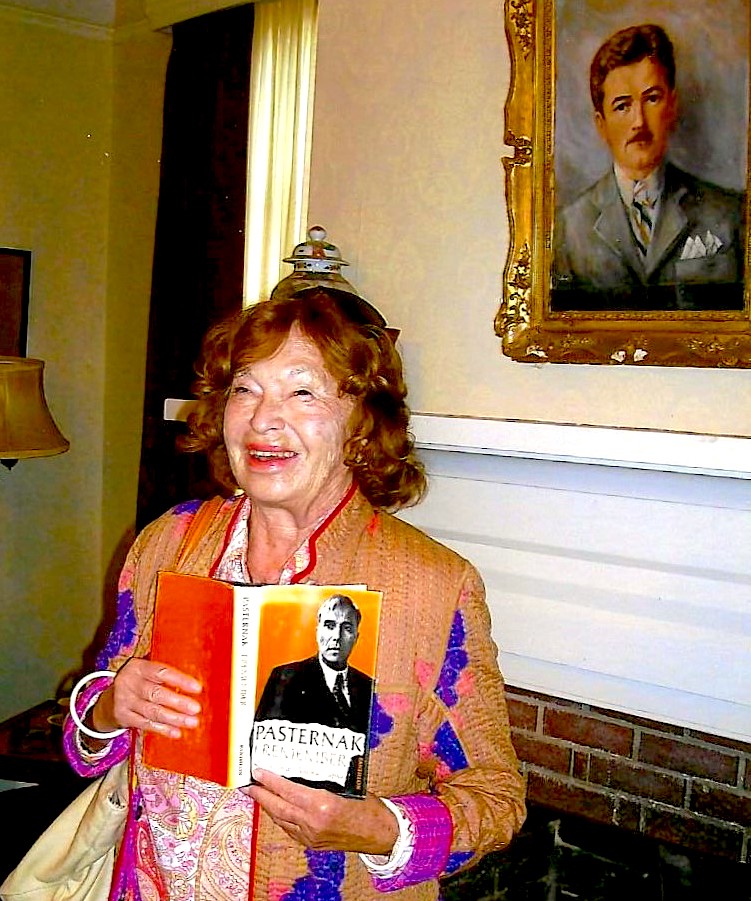

In Mississippi, as Faulkner looks on.

In Mississippi, as Faulkner looks on.

Morgan Entrekin, publisher (and cofounder of this website)

Inge Feltrinelli changed my life. When I first met her almost 35 years ago Inge welcomed me with what I would learn was her unflagging exuberance into the community of international literary publishers that included Ledig Rowohlt, Karl Otto Bonnier, Jorge Herralda and Lali Gubern, Christian and Dominique Bourgois, Jean Claude and Nicky Fasquelle, to name just a few—men and women who published books with commitment but also with passion and style and a sense of fun. These publishers weren’t corporations, they were individuals and families who published serious books—some had been doing it for generations. Books that introduced new voices, took chances and helped change the world.

These people, like Inge, first with her husband Giangiacomo Feltrinelli and later with her wonderful son Carlo, all have a deep commitment to social justice and human rights and to the writers whose books they bring into the world. And as my colleagues and I have worked over the last decades to build Grove Atlantic, this family of friends has offered support, inspiration and friendship in good times and bad. We could not have done it without them.

One Inge story: In the fall of 1999 at the Frankfurt Book Fair (of which she was the undisputed Queen), Inge hosted a party to celebrate the upcoming millennium. She convinced the men to bring a tuxedo to the fair (only for Inge), took over a lovely Italian restaurant, served delicious pasta and champagne and hired a band. It was a glorious evening and we were all dancing as it turned midnight when suddenly I saw Inge looking sad so I went over and said, “What’s wrong, it has been a wonderful night, great fun among our friends.” And she said “Well the band just said they have to stop playing, time’s up. “I said let me see about that. So I passed the hat, collected some deutschemarks (thank you Michael Klett) and went to the bandleader and told him how much fun Inge and we all were having. I asked if he and his colleagues couldn’t play just a bit longer. He agreed, the band launched into a lively song, Inge lit up with joy, and we danced until the wee hours of the morning.

So thank you Inge for that night and for so many, many other wonderful times and for so much inspiration. I’m sorry the music had to stop. If I could find the bandleader I would ask him to play on because none of us are ready for the party to end. But I know you are on to the next party, joining Ledig and Roger and Peter and all your other friends who are already there. Now that you’ve arrived that party can truly begin. Godspeed my beautiful friend.

With Morgan Entrekin. Photo by Rachel Cobb.

With Morgan Entrekin. Photo by Rachel Cobb.

Gary Fisketjon, editor

“A light can go out in the heart” is a line written by a friend that I quoted when a dear mutual friend of ours died, because I believed it was powerfully true. Which it still often seems to be, now 30 years later, except when this isn’t true at all.

The loss of Inge Schoenthal Feltrinelli is irreparable to more of us than anyone could count up, yet by this I mean her absence, of her not being here among us to brighten our rooms and our days and our joys and tribulations alike. Many people are excellent celebrants, none as spectacular as Inge, but what about the other 99 percent of our lives? At times when I haven’t known what I should do about some hideous conundrum, even what I could do in order to survive it, well, I turned more than once to Inge, who confronted much worse throughout her life, who demonstrated you can face down the very worst ordeals, chiefly on your own terms, and that rather than anxiously brood about or fearfully fight these impossible challenges you just need to get on with it—and when would a little sprezzatura come in handier?

“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, thereof one must be silent.” Inge is not immune to Wittgenstein’s truth. Anyone who loves her has countless memories thereof that define “precious,” and I’ll leave them all to their own and do the same myself. In mine, Inge’s right by my side, as she so often has been for so long. And this proves that the light mentioned above in fact doesn’t go out. Sure, it flutters and seems so fickle and feeble in this howling wind that it has to or will at any second. Nope, because it so happens that this pilot light in your heart will not give out. She who lit the wick will be reflected in those candle-flames until you give out. In the meantime, Inge ain’t going anywhere.

Thanks to Inge, we see how to have serious fun, and how much fun the most serious things really are—not a bad mantra, if you ask me. And, since I guess no remembrance is complete without some anecdote: I’ve lately been recalling her last visit to the South, when she proclaimed it the only place on earth where bourbon tasted delicious instead of “disgusting” and that she wanted to drink a glass of it at midnight while standing over William Faulkner’s grave. And after being given the key to the city of Oxford, she did exactly that, which grants this little story a nice shape, because earlier that day she’d toured Faulkner’s house Rowan Oak with infectious delight, which is precisely how she encountered and helped shape our global literature, as a singular publisher and simply as her own grand self.

Dominique Bourgois, publisher

Inge Feltrinelli believed in storytelling: fiction, essays, biographies, travel books, interviews, politics… She knew better than most that books bring us together.

My personal and professional life of the last 45 years would not have been the same without Inge. As a friend, as a mother, as a person, she was demanding. “How are you, how is the publishing house?” was not a question to be evaded. She made her work a life commitment, and she expected the same no dilettantism, just success and responsibility.

Inge set a great example of how to live: her taste for life, for meeting people, visiting new places, eating new food, her ever-famous wardrobe which made us looked so plain… her insistence that we should all be on our best behavior, always… She made us believe that we all belong to the Maison Feltrinelli.

Over the years we all had to make choices, fight, give talks, write columns; books were our tools and our weapons, as it should be. Inge always told me to pay attention to details from the book cover to the promotion. “Authors are always right; editors, translators and journalists must be taken care of. But publishers are in charge.”

Bookstores were always so very important. I briefly worked in the now-closed but then-famous bookstore in Paris, La Hune, on boulevard Saint Germain, after Inge told me I couldn’t be a good publisher without that experience. I am still grateful to her for this advice, and I have learned to call booksellers by their first names, to go and visit, to be partners with them. Bookstores bring us social cohesion when it is fading, and Inge knew that. Feltrinelli bookstores are necessary; the Feltrinelli Foundation in Milan was Inge’s last pride.

On the Friday night after she died, after the Town Hall ceremony in Milan, people danced in Feltrinelli stores around Italy to the soundtrack of The Leopard, the film based on the Lampedusa book; I was there and it was so moving—how Inge would have loved it.

We shared authors, we shared friends for life. Milan, Rome, Villadeati, Frankfurt, Berlin, Paris, London, New York, Panarea, Stockholm, Manneville, lago di Gardia, Mossna, Venice, so many more places… We met and were met by friends.

Now we are left with cherished memories, and a duty to pass on to the next generation a love of book publishing.