The Ballad of Steinbjørn Jacobsen

On Escorting a Faeroese Poet-Hero Around the USA

In memoriam, Steinbjørn Berghamar Jacobsen, September 30, 1937–April 12, 2012

When the phone rang that evening in 1978, I was caught off guard. “How soon can you be here in DC?” the voice was asking. I lived in Los Angeles. “And—you do know Old Icelandic, right?” Old Icelandic, spoken by the Vikings some thousand years ago, was extinct.

As I hung up, I wondered: How had my career come to this?

My Stanford PhD in Germanic Languages had led to my teaching at UCLA and then Pomona College. But in 1973 my position had been eliminated, and I found myself unemployed—and unemployable. Students were demanding “relevant” courses, and the traditional foreign language requirement had been abolished by colleges almost everywhere. Looking back on this today, I see I was ahead of the curve when it came to joblessness.

All I had been trained to do was teach. What other marketable skills might I have? Slowly I began to find work as a freelance translator. My first assignment dealt with German and French cat food. Thomas Mann had been replaced by KATKINS für die Katze and POUSSY pour le chat. The one bright spot was that I had passed the State Department examination for escort-interpreters in both German and Swedish.

The assignments for State were normally one-month stints during the summer; I would accompany foreign dignitaries across the country, always starting out in DC. But when my contact at Language Services called me on this Monday afternoon in July, clearly something was amiss. I figured the earliest I could get there would be Wednesday.

“I guess that will have to do,” Pavel told me. “At this point you’re all we could come up with. But you do know Old Icelandic, right?”

“Well, sort of,” I ventured, wondering why he was asking this. I had passed State’s oral exams in German and Swedish. “Where is this person from?” I asked. Had they stumbled upon a Viking frozen in a block of ice? I didn’t understand why he was being so evasive.

“How’s your Danish?” Pavel continued. “He does speak Danish. Sort of.” I tried to explain that although I could read Danish, spoken Danish is notoriously problematic. With all its slurred sounds and glottal stops, even the next-door Norwegians—much to their consternation and great annoyance—often can’t understand spoken Danish. Couldn’t they find a native Dane closer to DC? It was like this: One of their more seasoned escorts had been assigned to this visitor, but the first night he had made “advances” to her. She was discreet in giving the details—other than that he had been quite inebriated—but she had quit on the spot. Stranding him. Stranding them. There was a silence while I tried to absorb this. But there was more:

“Unfortunately, that’s only part of the problem. Steinbjørn”—I was amused that his first name meant “stone bear”—“doesn’t speak Danish. He’s a poet, from the Faeroe Islands. They have their own language.

“He’s supposed to speak Danish,” Pavel quickly continued. “Most natives of the Faeroe Islands do. But apparently he doesn’t. At any rate, not a Danish that the Danes can understand.”

“What makes you think I can understand him, then?”

“We saw on your résumé that you took Old Icelandic at Stanford. Won’t that give you a leg up?”

“We read the sagas in Old Icelandic, but we never spoke it. It’s a dead language.”

“Well, apparently his ‘Danish’ is something of his own invention, so if on your end you can invent some kind of Danish, then the two of you ought to be evenly matched. Anyway, see how soon you can come and we’ll book your flight. Oh, and it’s probably best if you meet him directly at your hotel. Steinbjørn has locked himself in his room and is refusing to come out. No one can talk to him.”

When I called Pavel back the next morning to arrange for my ticket, he provided a few more details. The Faeroes were up in the North Atlantic, halfway between Norway and Iceland. They consisted of an archipelago of eighteen major islands, populated by forty thousand souls, who spoke a language all their own. In the middle of nowhere.

I tried to imagine—a separate language for a country half the size of Santa Monica! And like Icelandic, the language had barely changed in a thousand years. It was a living relic, a far distant past that was still hanging in there, but as the present. And to represent the Faeroese, State had invited an alcoholic poet. As it turned out, Steinbjørn proved to be an important man. Just not in the way that our government had expected.

* * * *

Traffic was bad coming in from Dulles; I got to the Dupont Plaza around 7:00 pm. When I asked for Steinbjørn’s room number at the front desk, they seemed greatly relieved that at last someone had come to “take care of things.” They gave me a duplicate key to his room.

I knocked loudly, but there was no response. Reluctantly I let myself in. The air conditioning had been set at arctic. The floor was littered with tiny liquor bottles from the mini-fridge, as well as wrappers from Oreo cookies, Mars Bars, and Snickers. In a corner I saw a figure slumped down on the floor, leaning back against a wall, apparently sound asleep. All he was wearing was a colorful pair of paisley Faeroese skivvies.

I knelt down and shook his knee; slowly he opened his eyes. They were an amazingly piercing blue, but at this point too bleary to pierce much of anything. I told him my name and that I would now be his escort-interpreter. I was here; I would stay with him. I said this in my dodgy Danish, which he didn’t appear to understand. I tried again, pronouncing all the Danish sounds that are normally slurred or silent. Finally I sensed he was absorbing what I was saying.

Pulling him up by both hands, I was able to get him to his feet. I was surprised at how short he was. As he tried to bring me into focus, his eyes filled with tears. I put my hands on his shoulders, trying to steady him. I wasn’t ready for any of this. Although this assignment still seemed preferable to KATKINS für die Katze, I knew I was out of my depth.

Trying to keep him upright, I asked if he wanted something to eat. I used the Danish word “spise” and then the Swedish word “äta,” miming lifting a spoon out of an invisible bowl. He shook his head no. I heard “sove” as he mimed tilting his head down into his folded hands. So I led him into the bedroom.

I watched him crawl onto the rumpled unmade bed. Then, lying on his back, he stared up at me and broke into a smile before he closed his eyes. He didn’t say goodnight. All he said before he fell asleep was, “Eiríkur.” My name in Faeroese.

My instincts told me to call State immediately and tell them I couldn’t do this. But then they had already been stranded once. And I had given them my word.

* * * *

After I had put Steinbjørn to bed, I went down to the lobby and checked in. State had messengered over a thick packet of material for me, which included a bio of Steinbjørn, our month-long itinerary, plane tickets, and a small book in English that described the Faeroe Islands.

The Islands—Føroyar—are indeed halfway between Iceland and Norway. Apparently the name of the Islands derives from the Faeroese word for “sheep.” “At present,” the book informed me, “sheep are roughly equivalent to twice the human population of the Islands. Every winter, many sheep slip on the rocky slopes and plunge to their death in the sea.” The whole episode, it seemed, could have been written by Monty Python.

Reading further I learned that roughly 98 percent of Faeroese exports were related to fishing and that the Islands had been under Danish control since 1388. Since then Faeroese had been forbidden as a teaching medium in the schools. For a while it looked as if the language was facing certain extinction. It wasn’t until 1948 that school children were finally allowed to be taught in Faeroese instead of Danish. In that year the Home Rule Act granted the Islands special status as a self-governing community within the Kingdom of Denmark.

In 1970 the Faeroese withdrew from NATO. And somehow they managed to remain outside the “Common Market,” as the European Union was called back then. In 1946 there had been an independence referendum in which the people voted for secession from Denmark, but this was overruled. “It was a consultative referendum,” I read, “and the parliament was not bound to follow the people’s vote.”

This is where Steinbjørn came in. In addition to writing poetry and children’s books, he was known to be the Islands’ most vocal political activist. He wrote plays advocating complete independence from Denmark. His took his plays and troupes of players down to the docks. When the fishermen came in with their catch of cod, he incited them to join his demonstrations—demanding that the Faeroe Islands break away from Denmark.

The next morning I called State to check in. We still had a full day for sightseeing in DC before we were to fly off to our first official meeting with a professor of Comp Lit and Folklore at one of the Ivy League schools.

I mentioned that Steinbjørn seemed like an odd choice to invite for a high- level visit. Well, Pavel admitted, no one at State knew Faeroese, but they did know he was a political activist and a voice to be reckoned with as the Islands determined their future. If they did achieve total independence from Denmark, they would be a new nation. Before that happened, they wanted Steinbjørn to become favorably disposed to our country. “So that they might become our allies and not get sucked into the Soviet orbit,” Pavel said, only half tongue-in-cheek.

Nixon had “opened up” China six years earlier, but we still feared the “Red Menace.” In 1964, when I was hired to teach at UCLA, I’d been required to sign an oath that I was not a Communist.

“Once we saw him,” Pavel continued, “it occurred to us we may have made a mistake with this one. It all depends on you, Eric, as to whether or not this will work out.”

* * * *

By noon I felt it was time to wake Steinbjørn. I had no idea what to expect but hoped he would at least no longer be inebriated and crying. To my relief he was up and dressed. He was wearing a very plain white cotton shirt, with a simplicity that struck me as something the Amish might wear. His generic jeans were clean, and he wore spit-polished black dress shoes, something a boy might wear to his first Communion. His eyes were a pure blue, his cheeks were rosy, and the planes and angles of his face were quite striking. He could have been a poster boy for the Vikings if only he’d been taller.

We stopped by the first fast food place we found. Since all the items were depicted in saturated color on a sign behind the counter, all he had to do was point. While on most days I would’ve lamented this apparent slide into a language-less culture, that afternoon it was a welcome reprieve.

Once out on the street, Steinbjørn looked at the mass of humanity hurrying past. He had the unguarded curiosity of a child, and like a child his questions never let up. An elegant woman caught his attention; her burgundy silk dress was so beautiful that I could tell it was something special. She wore spaghetti- strapped shoes with stiletto heels that looked virtually impossible to walk on.

“Om skoarna eetje errr smerrtilika?” Steinbjørn asked. “Om hun eetje ramlar omkull ibland?” Were her shoes not painful? Did she not topple over occasionally? I told him apparently not; she seemed to be walking just fine. “Sprrrrrrrrrrk!” he demanded. “Ask!”

He started trotting behind her, looking at her feet. I tried to explain one didn’t ask strangers that kind of thing. But he got louder each time he commanded: “Sprrrrrrrrrrk!” So I caught up with her and posed the question. Her expression was incredulous. Didn’t I understand the rules of civilized behavior? When I went back to the expectant Steinbjørn, it was easier simply to tell him that yes, they were extremely painful to wear. And she had indeed experienced great falls wearing these shoes. He beamed at me. I had asked!

The next person who caught his eye was a willowy young African American woman with cornrows. Her braided hair was intricately woven into tight patterns very close to her scalp. Steinbjørn wanted to know what kind of hairdo this was and why she wore it. “Sprrrrrrrrrk, Eiríkur,” came his command: “Sprrrrrrrrrk!”

I had no Danish word for cornrows and no insider’s knowledge as to the custom.

When I went up to ask her, she smiled at Steinbjørn and looked right into his preternaturally blue eyes. He greeted her in Faeroese. She hesitated for a moment, then said, “You like my hair, child?” And in the melodic rhythms of Jamaican English, she gave us a detailed lecture on cornrows. I found I didn’t need to translate. Steinbjørn was captivated by her warmth and her accent.

* * * *

The flight to Boston had been just a short hop. Steinbjørn seemed anxious about our first academic appointment. He was wearing his same outfit—white cotton shirt, clean pair of jeans, and polished black shoes—only now he was carrying a very worn old leather satchel. The professor who had agreed to meet with us ushered us into the conference room of his department, rather than just his office.

Professor R. greeted us with hearty pleasantries and asked Steinbjørn if he’d like some coffee. The department secretary had brought in a steaming pot, along with a sterling silver creamer and matching sugar-cube holder. “Kaffi,” said Steinbjørn. “Ja, takk!”

Professor R. slid across the table to us a folder that resembled a press kit. It contained his CV, a lengthy list of publications, and offprints of a number of his scholarly articles. Many of them dealt with Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I noticed that he was an Endowed Chair.

“Överrrrrsett!” Steinbjørn called out. I had no idea how to translate “endowed chair.” To me the term had always had a slightly salacious ring to it. So I “translated” for Steinbjørn in our still-evolving idiolect, giving him generalities about the importance of our host.

Professor R. had a kind face. He told me he set great store by high-level meetings of scholars, and was grateful to the State Department for helping bridge the gulf between linguistics, folklore, and world literature from all eras. He mentioned he was eager to learn Steinbjørn’s spin on the Green Knight: whether he favored the interpretation of his being the Green Man of traditional folklore, or rather of his being a Christ figure. How did all this fit into the overall Arthurian legend? How could so many ambiguities be resolved? What did Steinbjørn have to say?

In translating I used the Swedish word riddare for knight. Den gröne riddaren. This made no sense to Steinbjørn, who had never heard of Sir Gawain. He asked how a knight could be green. “Sprrrrrrrrrrrk!” he demanded. Clearly I must have been wrong. Clearly I had misunderstood!

The light reflecting off his round spectacles, Professor R. began his own exegesis of the Green Knight. Steinbjørn, without seeming aware of it, had begun to remove the sugar cubes from the sterling silver container and to stack them up, forming a kind of pyramid. When Professor R. noticed this, he stopped speaking.

Steinbjørn apparently felt this meant that the man was finished. He leaned down to open his vintage leather satchel and produce a small book. He walked around the table and slid down to crouch at the professor’s side, with me standing behind him, and placed the book onto the table in front of him. It was a very slim volume, almost more of a pamphlet than a real book. The paper was of the same poor quality as propaganda flyers in East Berlin.

“Överrrrrrrsettt!” Steinbjørn instructed. Without ever having read any Faeroese before, I found I was able to translate the title of what was clearly a Faeroese children’s book, Hin snjóhvíti kettlingurin. “The snow-white kitty- cat,” I translated. The professor’s expression suddenly congealed. Something was deeply wrong. For my part, I felt I was back at my PhD orals at Stanford, where I had been called upon to sight-read a passage from one of the sagas in the original Old Icelandic, Brennu-Njáls Saga, the Burning of Njál. I was both surprised and relieved that I was able to sight-read the book about the kitty-cat in a language I had never seen before.

Steinbjørn turned to a random page in his book. Kettlingurin var kritahvítur, hann hevði ikki ein myrkan blett á kroppinum. “The kitty-cat was white as chalk, he didn’t have a single fleck on his body.” This time it wasn’t my PhD orals, so I could relax. What I didn’t understand, I made up, easily guided by the colored illustrations of happy children in their brightly colored Faeroese sweaters and the snow-white cat that was white as chalk. “Well,” I said, looking up from the slender book, “I’m sure this will give you the overall idea.”

Judging from the professor’s expression, I could see he was mentally shifting gears. Clearly Steinbjørn wasn’t the high-ranking international scholar he had expected him to be. I explained that there wasn’t much written in Faeroese, and that Steinbjørn’s children’s books were an invaluable learning tool for schools and parents back home in his Islands. Professor R. seemed to be taking this all in.

In a beautifully flowing script, Steinbjørn penned a dedication to the professor on the back cover of the slim volume, then autographed and dated it. With great ceremony he presented it to him. Then he went back to the other side of the table and put the CV, the offprints, and the publication list into his satchel. They smiled at each other as they shook hands. I took a parting look at the sugar-cube pyramid on the table.

Professor R. clasped my shoulder warmly as he guided me out the door. In a quiet voice he told me, “This was quite refreshing. I teach folklore—but I almost never come into any living, breathing contact with it.”

I was greatly relieved that the meeting had not turned into a fiasco. “We’re counting on you,” State had told me. Well, maybe I might actually be able to pull this off.

* * * *

Our itinerary was a bit of an odd zigzag across the country, since our meetings depended upon our hosts’ availability. We next flew to Lexington, Kentucky, and drove through breathtaking rolling hills to a small Appalachian town. We were to meet with a man who had made a short documentary film about coal mining. On our itinerary he was listed as a “political activist playwright,” which was what Steinbjørn was supposed to be and was the reason State had invited him here.

Many boys in rural Appalachia, we’d been informed, were leaving school early to work in the mines; many of them did this for instant earnings. They wanted to be somebody now; sadly, most often their highest priority was to spend the money on a flashy car. The film was called In Yer Blood, because in that part of the world mining was deeply entrenched. It would almost be unusual for a boy from a poor family not to go into mining. But black lung disease, for which there was no treatment, was not uncommon, nor were horrific mining accidents. The underlying message of the film was that this practice was the equivalent of sending the boys into the trenches. The writer/director was hoping for widespread distribution of the film in schools throughout the area, as a warning.

We watched the film along with the young director, as well as eight or so teenage boys who had appeared in the film. Clearly they were quite poor. Already some of them had rotting teeth, but they smiled as if that didn’t matter. The boys took an instant liking to Steinbjørn.

One cowlicky boy with freckles mentioned that most of the time they didn’t have much food at home, so he would be lucky if he could shoot a squirrel for breakfast. There wasn’t much meat on a squirrel, but with a nice gravy he could eat it with biscuits. Translating, I drew a blank on all the Scandinavian words for “squirrel.” I told the boy I didn’t know the word off-hand, so without missing a beat he hopped down from his chair and sank to his haunches, twitching frantically with his nose, holding up his hands in a mendicant’s position, darting his eyes skittishly back and forth. “Ekerrrrrrn!” Steinbjørn said, in immediate recognition. He too hopped down from his chair, and for a long moment Steinbjørn and the boy became mirror-image squirrels. Then they both broke up in laughter.

Still crouching as a squirrel, the freckled boy—his name turned out to be Lanny—asked me if we were familiar with “haint” stories. Here I was at a loss, but the director explained they’re a kind of ghost story popular in Appalachia, about restless spirits who come back to “haint”—haunt—the living. They’re best told to a group sitting in a circle around a remote campfire as the storyteller casts his spell. “Done properly,” the director told me, “these tales can scare the bejesus out of the listeners.”

Lanny got up to dim the lights so that we were in almost total darkness. As our eyes adjusted, he instructed us to sit around in a circle on the floor. When we were properly assembled, Lanny began to tell his tale. His coal-black eyes darted around the room far more warily than when he had been the alert but anxious squirrel. His voice was sonorous and almost caressing—but it was an unsettling caress. His rhythms were almost purely Appalachian and it was hard for me to follow the dialect. What I got was the gist of the story, in which some kind of horror had started its slow build. As Lanny let his story unfold, Steinbjørn sat there in complete absorption. He didn’t understand the words either, but he understood the tone of menace, and even in the shadows I could see his Nordic blue eyes grow wide as he leaned in to listen.

* * * *

Our next appointment was with a Comp Lit professor at a large Midwestern university. Professor K. looked young and vulnerable. He sized us up for a long moment, then was visibly relieved. Apparently Steinbjørn did not look the part of the imposing intellectual he had come to expect. “I think I’m going to enjoy this visit,” he said.

“The Department makes me host all the ‘visiting firemen,’” he confided, “and the last one just about did me in. He was one of these über-intellectuals for whom literature is something remote and abstract. He swept me into a thick cloud of Ingarden’s phenomenology and Dilthey’s hermeneutics. To be honest, scholarship like this has always scared me.” I told him that I had my own horror of hermeneutics, and it occurred to me for the first time that maybe my freedom from academia was not the tragedy I’d always assumed it was.

“I understand you’re a poet!” he said, turning to Steinbjørn. “Yrkjari,” I translated as Steinbjørn beamed. “And that you write children’s books. Do you have any samples of your work?”

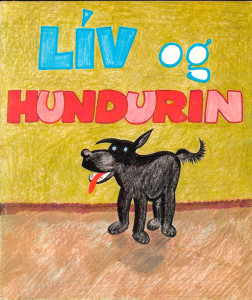

I translated this for Steinbjørn, and the next thing I knew he was over on the young professor’s side of the table, presenting a small children’s book that I hadn’t seen before: Lív og Hundurin. On the cover we saw a girl named Lív and a blue-eyed dog with a long red tongue.

Lív æt ein lítil genta, hon var rund og næstan altíð glað. I was able to sight-read the Faeroese: “Lív was a little girl, she was round and almost always happy.” In the colored illustrations, Lív played with her dolls, and her friends Kára and Hanur and Eyð played with their building blocks—when one day Mamma opened the door and out of nowhere there appeared a blue-eyed dog. It smiled at Lív, a long bright red tongue extending down from its eager smile. Professor K. looked rapt. I explained how Steinbjørn was writing these books so that Faeroese children, whose language had once been banned and almost died out, would have something to read. That he was presenting them with—and preserving—their own culture. The boy had the Faeroese name Hanur, not the Danish name Hans. And until Steinbjørn came along, school children had been reading Anders And—“Donald Duck” in Danish. “You know, they look like a lot of fun,” Professor K. observed wistfully. Steinbjørn didn’t ask me to translate this. From the professor’s expression he could tell that whatever he was saying, he was happy.

* * * *

While Steinbjørn slept on our flight to San Francisco, I tried to take stock of our situation.

Neither of us really spoke Danish. My “Danish” was essentially Swedish with Danish words thrown in. Steinbjørn was certain that his Danish was very solid, but he spoke it pronouncing all the silent consonants, with an extravagant trill to his r’s, and shamelessly sneaking in words from the Faeroese. My mind was constantly making adjustments: For “boy,” dreng became drongur; for “English,” engelsk became enkst. The most confusing shift for me was to realize that in Faeroese svanger—in German the word schwanger means “pregnant”—means “hungry.” But gradually I understood and incorporated more and more Faeroese, and our two versions of “Danish” more or less merged. No outsider would ever have been able to understand us.

But there was one aspect of Steinbjørn that was beginning to worry me far more than his “Danish.” One morning when I had gone into his hotel room to pick him up for an early flight, I found propped up next to his suitcase a fifth of Southern Comfort, with about two inches of “Comfort” left at the bottom. He suggested maybe there wasn’t enough to keep. Would I like some? At 6:00 am? Hardly. So he chugged the remaining two inches—like something out of a fraternity initiation—and then tossed the bottle into the wastebasket.

These bottles were becoming a regular phenomenon. If it wasn’t Wild Turkey, it might be Old Crow or Jim Beam. In the book on the Faeroe Islands, I had read that anything other than a virtually non-alcoholic beer had to be specially imported, and was sold at horrendous prices. In addition, according to Faeroese regulations, “it is a breach of the law to consume any alcoholic drinks in a restaurant or other public place.”

Here Steinbjørn was taking full advantage of the relatively low price of alcohol and his unlimited freedom to drink. But I was becoming increasingly concerned. I hoped I had made the right decision in not calling State to tell them about this. I was afraid they would send him home. But I was also afraid I was enabling him to develop an addiction from which he might never recover. On the other hand, he was the visiting dignitary and I was merely the escort, the “lowly interpreter,” to use a term I had once encountered in Time magazine.

Was it my responsibility to intervene? In the end, I made my decision by not making a decision.

* * * *

In San Francisco we rented a car and drove down to San Juan Bautista, 17 miles north of Salinas. A rather remote town, it was the home of El Teatro Campesino, which loosely translates as the “farmworkers’ theater.” The original actors all worked in the fields, and the group had been founded by the United Farm Workers. I realized we were invited here because State considered Steinbjørn to be a “political activist playwright.” And the Teatro Campesino fit right into this category.

The troupe, which had started out performing Aztec and Mayan ritual dramas, had moved on to broader aspects of “Chicano” culture—as it was then called—including a focus on the Vietnam War and racism. It was here that Luis Valdez premiered his play Zoot Suit, which had gone on to Los Angeles and then even to Broadway and a 1981 film.

At the time we visited them, they were between productions, but they greeted us warmly. They had a lunch ready for us at outdoor picnic tables, introducing Steinbjørn to tacos and burritos, corn-husk tamales and nopales—cactus as a vegetable. He loved Dos Equis and Corona and Negra Modelo. And he helped himself liberally to straight shots of mezcal from a bottle that contained a gusano—the ritual worm.

Many of the children spoke only Spanish, but when Steinbjørn went up to play with them, language proved irrelevant. They showed Steinbjørn some of their folk dances; he watched attentively and then joined in. He joined their circles, arm in arm, as they swayed about, knowing what dance steps came when. And when he gave them instructions on some of his dances in Faeroese, the children caught on almost immediately.

Then one of the children—a little girl in a frilly party dress—hit on the idea of stringing up a piñata to show him, even though it wasn’t Las Posadas or anyone’s birthday. They explained to Steinbjørn that he must break the piñata hanging above—a container in the shape of a donkey, covered in papier-mâché—with a special bat. Blindfolded! They sang songs as they spun him around and around and around. Dizzy from the whirling and the Dos Equis and mezcal con gusano, he made wild swings with the bat. He kept at it with a joyous frenzy until pow! he managed to connect with a crisp perfect crack. Steinbjørn fell to the ground laughing, still blindfolded, as a torrent of fruit and peanuts, small toys, wrapped candies, and confetti rained down upon him.

At that moment everything went black. From behind me, someone had slipped a blindfold over my eyes and I felt a bat poking at my hand. “Te toca a ti!” a young boy’s voice told me. And then I was sent awhirl as childish voices were singing, “Esta piñata es de muchas mañas, solo contiene naranjas y cañas.”

For all my languages, I’d never studied Spanish, not even in high school, and yet like Steinbjørn I found the joy of that afternoon infectious, beyond any need for shared language or culture.

* * * *

In Berkeley we had an appointment with a Professor B., who taught folklore. This was to be the last of our formal meetings with professors, for which I was grateful. So far we had made it through them unscathed, but by now Steinbjørn seemed to be in a constant alcoholic fog. At times he lurched noticeably; even casual observers could sense there was something amiss. He was very loud and we were always the center of attention.

Again we sat in a conference room. Steinbjørn had brought his leather satchel but left it on the floor by his feet. Professor B. seemed pleased to see us. I translated his cordial greetings, but this time Steinbjørn just sat there, looking down, sunken in thought. He didn’t say anything. I asked him if he was all right.

Then slowly, resolutely, Steinbjørn got up and strode over to a blank wall. He looked at us, intently, then at the wall, intently. Then he held out his arm at full length and began to trace large circles on the wall; circle after circle. He would fix us with his gaze, then look intently back at the wall. Then more circles. And more circles.

Professor B. seemed to be taking all this in stride. Steinbjørn, who appeared to have finished, proclaimed loudly, in English: “I have vrite a poom!” Then he stared at the wall and at the invisible circles, while Professor B. and I looked on. I said quietly that Steinbjørn was a poet—perhaps first and foremost a poet, although he also wrote plays and children’s books. “He’s very respected in his Islands,” I added, hoping that he was.

Steinbjørn stood there looking at the blank wall. Then abruptly he went back to the conference table, scooped up his satchel, and headed out the door. Professor B. still seemed to accept all this as being within reason. Or, if not within reason exactly, something that transcended reason, or to which reason no longer applied.

“You clearly have your work cut out for you,” he said to me.

“I’m just hoping to get him home in one piece,” I said. By that point I hoped that the trip would not kill him. His alcohol intake had just kept escalating, and by the time I realized how far gone he was it was too late to try to stop him.

“That thing with the circles,” he said, “I’ll have to try that in charades sometime. See if anyone figures out that it’s a poem. Or should I say ‘poom’?” He reflected for a moment, then added: “In an odd way, one could say that he himself is the poem. If that makes any sense.”

It did. By now it made perfect sense.

* * * *

Before we began to make our way back to the East Coast, as a special treat State had arranged for us to stay at a cabin-like hotel within a short walking distance of the Grand Canyon. Steinbjørn loved the rustic décor and the large pitchers of red wine that could be ordered with dinner—and the pitchers just kept coming.

The next morning, right after breakfast, we walked the short distance over to the rim of the Canyon. It must have appeared to Steinbjørn like something out of a saga—a gigantic fjord now plunging straight downward into the earth. He seemed transfixed. There was a pathway for walking down inside the Canyon, and a few tourists were venturing a short way down in order to take photographs.

I was standing there lost in the immensity of the Canyon, when Steinbjørn took off his white cotton shirt and handed it to me, and then his polished black shoes. “Eg gårrrr inn!” he proclaimed. He was going to go in. It was just a dirt pathway; apparently he wanted to keep his shirt and shoes clean. Before I could say anything, he was out of sight.

And then I waited. After some twenty minutes or so I sat down on a bench, carefully folding his shirt and keeping his shiny black shoes within sight. And I waited. I sat there with ever-increasing anxiety for several hours, and still he didn’t return. It was hard to make any sense of this. Finally I went into the hotel restaurant, figuring Steinbjørn could find his way back. Maybe he’d turn up for a late lunch.

By late afternoon I had gone from anxious to frantic. Had I lost him? Where did he go? He was shirtless and without shoes! I sat in the lobby trying to read a novel but wasn’t able to concentrate. Back then, cell phones were just as wishful a fantasy as Dick Tracy’s two-way wrist radio, so Steinbjørn was completely on his own. I would just have to wait.

I couldn’t think of any explanation for Steinbjørn’s disappearance. Had he been mugged? What kind of people went down this path, anyway? Had he decided to go all the way to the bottom? Had he fallen and was lying alone and in pain in the dark?

I was sitting in our room at about 10:00 pm, wondering if I should call State, though I knew no one would be there at that hour in DC, when suddenly and dramatically the door to the room burst open. Steinbjørn—his face, arms, and upper body lobster red—came staggering in and collapsed on the floor, emitting a small cloud of dirt.

“Eg må bada,” he said weakly. Well, yes, a bath would definitely be in order. I ran the water for him in the old-fashioned tub, then helped steady him as he undressed. The top half of him was a bright alarming red, and below the waist he was as white as the underside of a fish. His feet were raw and swollen. He was in a daze.

Had he gone to the very bottom? He had! But after the sun had set it had turned very cold and he had to run all the way back up from the bottom. He hadn’t had any food or water with him. Didn’t he get hungry?

He did. When he realized he had neither food nor water with him, he hailed fellow hikers. In the language that existed only between the two of us, he told me he had asked people if they had a súrepli to give him: an apple. He proudly explained that he had actually spoken English. He had told other hikers, “I sing you for an apple!” People, sensing something was wrong, must have been solicitous of him, giving him water to drink as well as apples and perhaps even sandwiches. He told me he planned to write a memoir about his trip to America.

He would not entitle it the Faeroese “Eg sang fyri eitt súrepli!” It would be just what he had told the other hikers, in English: “I Sing You for an Apple!”

I sat on a stool while he soaked in the bear-claw tub, drifting in and out of sleep. I had to be watchful that he not let his head sink below the waterline and drown. Finally I helped Steinbjørn get into bed. Instinctively, I pulled the covers up to his chin to tuck him in.

I needed to clear my head, so I decided to go back outdoors. Off the hotel lobby was a spacious gift store and I bought a pair of soft, beaded moccasins that Steinbjørn could wear until his feet had healed enough for his dress shoes again.

Then I walked over to the rim of the dark canyon. It was a strange sensation: what lay in front of me was pitch black, a vast unseen void. It was both eerie and calming.

I realized that if I hadn’t been thrown over the walls of Academe, I wouldn’t have been sitting there at the moment. At Pomona College, with no grad students, my life had narrowed down to teaching case endings to eighteen-year-olds at eight in the morning. I spoke German and they didn’t, so there wasn’t very much I could learn back from them.

Now, as a translator and sometime escort, I never knew what might lie ahead. One day I would be translating a Swedish child-custody dispute that led to the kidnapping of ten-year-old Felix. The next it might be a German art historian with a new interpretation of Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram, the assemblage of a stuffed angora goat encircled by an automobile tire. I translated for both Playboy magazine and National Geographic. In addition to the State Department, I found myself working for the German FBI, the LA Philharmonic, and the J. Paul Getty Trust. When the Olympic Games came to LA in 1984, I was an interpreter for the West German water polo team. For the Disney Aladdin film, I had to spend a day with Gilbert Gottfried—the voice talent who later went on to become the voice of the Aflac duck—coaching him to say his lines in eight different languages for his role as Iago, the “wisecracking parrot.”

Sitting at the dark shimmering void of the Grand Canyon that night in 1978, I had no idea where my career would lead me. But I knew it would continue to surprise me, and that I would not have been able to turn back.

* * * *

Years later, in 2007, I went onto Google and searched for him: Steinbjørn B. Jacobsen. I hadn’t thought about him in years, but there he was.

The Faeroe Islands were in the throes of celebrating his 70th birthday. The text was all in Faeroese, but once again I was able to get the gist. The photos revealed that Steinbjørn’s hair had now turned white, but his eyes were still a piercing blue. His face was boyish and yet—wearing a charcoal gray suit and holding a book up by his chest as if posing for a painting—he had the gravitas of an elder statesman. Extravagant bouquets abounded.

All of the capital city Tórshavn seemed to have turned out to celebrate his birthday. Judging from the crowds, I could see that he had become a national hero. At the time of his visit, I had had no idea how important he was in his Islands, nor to what degree he was loved. In translating his books for the various professors we met with on our trip, I hadn’t realized the full magnitude of his accomplishments. This was a language that had come close to extinction; now thanks to the children it was being kept alive.

I scrolled through the list of his works, which was exhaustive. Plays, children’s books, works for adults. But nowhere did I see either “Eg sang fyri eitt súrepli!” or “I Sing You for an Apple!” So I realized it was up to me to tell his story.

Of course I didn’t know any of this back then, while the sunburned Steinbjørn lay sound asleep in our hotel room. At the time I was overcome with relief at not having lost him under my watch. No headlines crying out, “Acclaimed Poet Meets Tragic Death; Interpreter Arrested.” He was safe; I was safe. My mind began to float away as I sat there near the edge of the Grand Canyon, contemplating the unending blackness.

I don’t know how long I sat there.

Eric Wilson

Eric Wilson’s work has appeared in The Massachusetts Review, Epoch, Carolina Quarterly, Witness, Boundary 2, German Quarterly, and O. Henry Prize Stories. After a Fulbright year at the Free University of Berlin, he went on to receive a PhD in German Literature at Stanford. Wilson taught German at UCLA and Pomona College; Harper & Row published his college-level German textbook Es geht weiter in 1977. Subsequently he was a freelance writer and translator, and taught fiction writing at UCLA Extension for thirty years.