The Art Scene Rebels of San Francisco

On 2322 Filmore Street, home of Painterland

The building that became known as Painterland was home to an array of painters, poets, and musicians from around 1950 to 1965. Located at 2322 Fillmore Street in the Fillmore neighborhood of San Francisco’s Western Addition, the simple four-unit structure became the center of the close-knit communities, galleries, and other alliances that formed nearby during these years. Painterland was a latter-day West Coast Bateau-Lavoir: home, studio, and meeting place to a revolving cast of artists, filmmakers, and poets, not unlike the dark, flimsy buildings in the Montmartre section of Paris that provided a fertile living, working, and meeting place for Picasso and his compatriots in their early years. The poet Michael McClure, a sometime occupant who moved into an apartment on the top floor there with his wife, the poet Joanna McClure, in 1956, dubbed it Painterland.

The three-story building had a storefront on the ground floor (occupied by a flower shop, according to McClure) and four flats on the floors above. A poignant photograph of Bekins Moving & Storage Company workers forklifting Jay DeFeo’s monumental work The Rose out of her second-floor home and studio there on November 9, 1965, while DeFeo stood watching from the fire escape above, captures the last day the artists inhabited the building [fig. 2]. Although Painterland was integral to this community—the artists themselves, in later interviews, often referred to their years together there as key to their development—almost nothing has been written on the building and the important activities that occurred there.

Figure 2

Figure 2Bekins Moving & Storage workers remove The Rose from Jay DeFeo’s home and studio at 2322

Fillmore Street, November 9, 1965. Courtesy of the Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley

When the McClures moved to Fillmore Street in 1956, the Bay Area figurative painter James Weeks (1922–1998), who was a colleague of Richard Diebenkorn’s at the California School of Fine Arts, already lived in the building, together with his wife, Lynn Williams Weeks, also a painter. Other tenants included the musician James “Jim” Newman (b. 1933), who founded the Dilexi Gallery in 1958; the painter Craig Kauffman (1932–2010), later associated with Los Angeles’s “Cool School,” who shared Newman’s flat for a time; and the painter Ed Moses (b. 1926), another artist identified with Los Angeles, who with his wife, Avilda Peters, took over Newman’s third-floor flat for a year beginning in 1960. Moses in turn gave the flat to the painter Les Kerr (1934–1992) in 1961; Kerr and his wife, Mary Kerr (b. 1937; later a documentary filmmaker), lived there until 1964.

The saxophonist and artist Paul Beattie (1924–1988) also lived in the building in the early 1950s. Beattie was a member of the Studio 13 Jass Band at the California School of Fine Arts when Hedrick joined the group in 1954; Beattie brought Hedrick and Jay DeFeo home for dinner one evening, and both artists were, in DeFeo’s words, “overcome” by the space. “It was just an enormous flat, really huge. It just seemed to go on and on. Of course it was dilapidated.” When in early 1955, Beattie and his wife moved out, Hedrick and Jay DeFeo took over the Beatties’ second-floor unit for $65 a month.

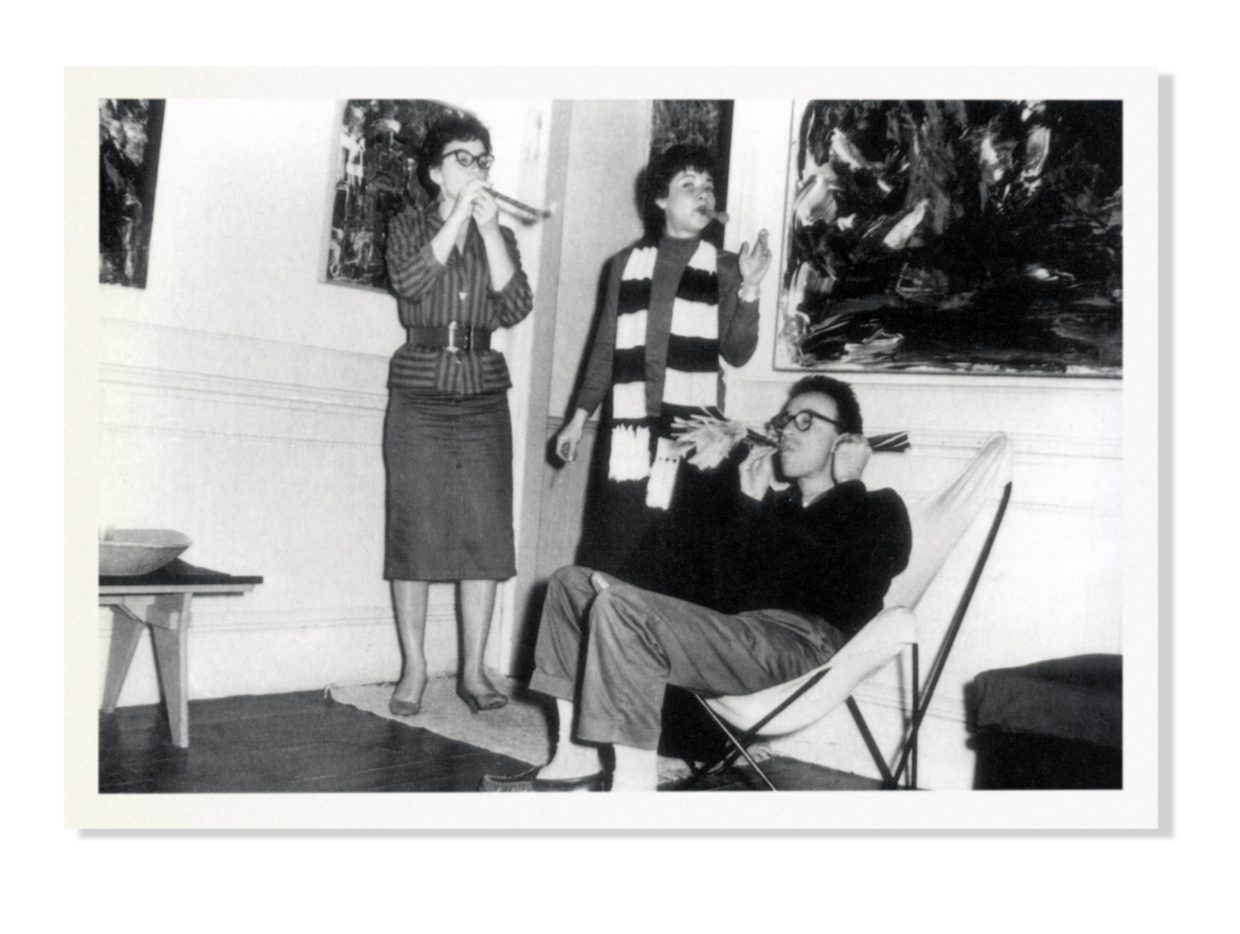

The painter Sonia Gechtoff and her husband, the painter James “Jim” Kelly (1913–2003), also moved into the second floor of the building in early 1955 [fig. 3]. The couple left for New York soon after Sonia’s mother, Ethel “Etya” Gechtoff, owner of the East & West Gallery just down the street at 3108 Fillmore, died of a stroke in summer 1958. Joan Brown and her husband, the figurative painter Bill Brown (1932–1980), took over Gechtoff and Kelly’s flat, next door to DeFeo and Hedrick, soon after. (Gechtoff recalls selling her refrigerator and stove to the Browns, because the apartments were not rented with appliances.) Not content to be just neighbors, the two couples, who had met through the Six Gallery in 1956, cut a door-size hole in the wall between their apartments so that they could come and go more freely [fig. 4]. “We got very tight with Wally Hedrick and Jay DeFeo, really tight,” Brown told an interviewer in 1975.

Figure 3

Figure 3Sonia Gechtoff, Jay DeFeo, and

Jim Kelly on New Year’s Eve, 1957.

Photograph by Wally Hedrick

Manuel Neri moved in with Joan Brown when she and Bill separated; their flat was eventually passed on to the painter and musician Dave Getz (b. 1940), who was finishing his studies at the San Francisco Art Institute. When the McClures moved out, DeFeo and Hedrick kept their second-floor apartment and took over the McClures’ third-floor apartment as well. As DeFeo told an interviewer in 1975, “We adopted the upper flat and the place became a bigger party area than ever. We really had everything.”

For nearly fifteen years, the building McClure nicknamed Painterland was a favorite stop for poets, artists, critics, and curators alike, from around town and as far away as New York City. The artist Fred Martin (b. 1927), who was the director of exhibitions at the California School of Fine Arts (or CSFA, renamed San Francisco Art Institute, or SFAI, in 1961) from 1958 to 1965 and director of the institution from 1965 to 1975, recalled visiting DeFeo and Hedrick’s apartment repeatedly over the years, usually with guests from out of town in tow:

In those days . . . one of my jobs was to take visiting curators, critics, [and] directors around, and I would always take them to Jay and Wally’s place—for lunch preferably, because the setting would just make their eyes pop. The way the rooms were, the height of these rooms, the way Jay’s big Rose painting was at the end of these rooms, the way there were Jay’s and Wally’s things everywhere, the way Jay would do her lunch with a hundred little bits of things: it was like a Chinese lunch. It was by far the most arty [place]. . . . I guess it was fifties bohemia.

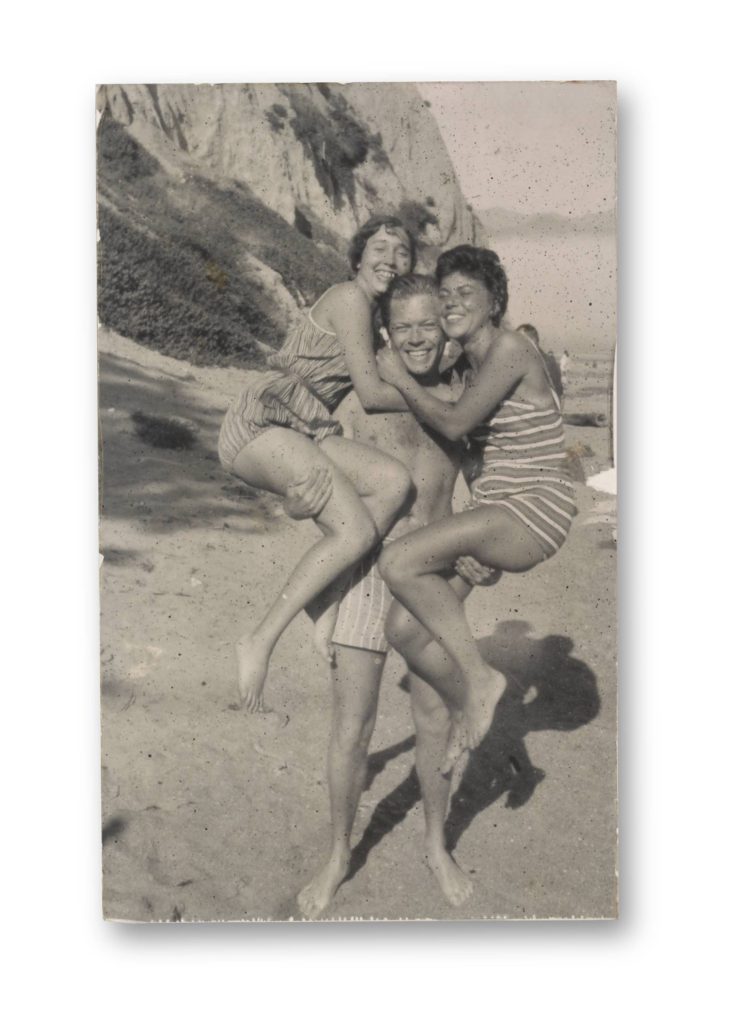

Figure 4

Figure 4Unidentified photographer, Joan Brown,

William Brown, and Jay DeFeo at Bolinas

Beach, between 1957 and 1960. Jay

DeFeo papers, Archives of American Art,

Smithsonian Institution.

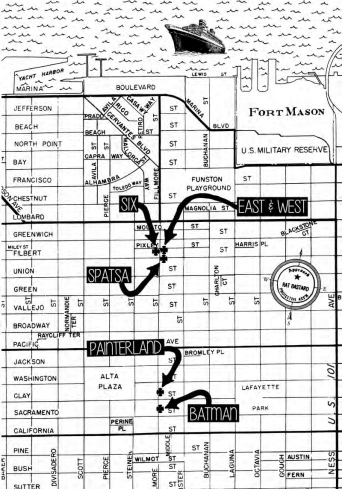

Capitalizing on the popularity of the Fillmore neighborhood for its cheap rent and the attraction of being near Painterland, a number of artists, poets, and musicians opened galleries in the Fillmore between 1952 and 1965 (fig. 5). King Ubu Gallery, begun by Jess, the poet Robert Duncan, and the artist Harry Jacobus (b. 1927) opened in a former garage space at 3119 Fillmore Street, near the corner of Fillmore and Filbert Streets. Hoping to help make ends meet, Jacobus opened Pere Ubu Restaurant about two miles west, at 321 Ninth Avenue. Jess and Robert designed the menus; Jacobus did all the cooking and painted each of the seventeen walls a different color. The restaurant did not last long and neither did the gallery. King Ubu operated for a year, from December 1952 to December 1953. When it closed, the artist-run Six Gallery opened in its place. Hedrick was one of the six co-founders, together with Hayward King, Deborah Remington, John Allen Ryan, David Simpson, and Jack Spicer. According to Ryan, “It was exactly what we wanted. Anything that we wanted to have happen could happen.” Hedrick was its first director and Manuel Neri, its last; the gallery closed with a poetry reading and the smashing of a piano on December 1, 1957.

Figure 5: Map of the Fillmore neighborhood, 1953–64.

Figure 5: Map of the Fillmore neighborhood, 1953–64.

To help fill the gap left by the closing of the Six, in early 1958 a young art student and fan of the Six named Dimitri Grachis opened the Spatsa Gallery nearby, at 2129 Filbert Street, in a one-car garage he rented for $35 a month. Spatsa Gallery shared a backyard with Etya Gechtoff’s East & West Gallery, which had opened across the street from the Six in May 1955 (and closed with Gechtoff’s death in July 1958.) The Painterland tenant Jim Newman partnered with Robert “Bob” Alexander to open the Dilexi Gallery a little over a mile away, at 721 Broadway, in 1958. Newman and Alexander also opened a branch of the Dilexi in Los Angeles in 1962 that closed in 1963; the San Francisco branch remained open until 1970. Finally, William “Billy” Jahrmarkt and his wife, Joan Jahrmarkt, opened the Batman Gallery at 2222 Fillmore Street in 1960. It remained open until 1965, closing because of the same rent hikes that forced DeFeo and Hedrick out of their flat just up the street.

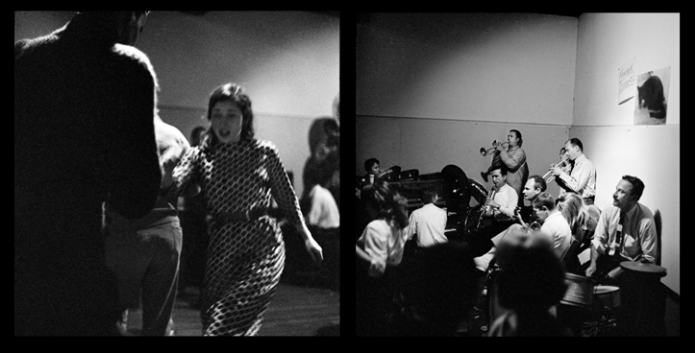

Etya Gechtoff nurtured a stable of older Bay Area Abstract Expressionist painters at her East & West Gallery and made regular sales of their artworks. The directors of the younger artist-run galleries, however, typically kept irregular hours and used their spaces for performances, poetry readings, and parties. These galleries sold very little work and the spaces became—like Painterland and the nearby coffee shops and bars—just another setting for sharing ideas, socializing, and making art. For that reason, a lot of the art was ephemeral, made from materials deemed worthless. “The rattier the better,” Conner later recalled. “There wasn’t much point in making anything that would have any function in the art world itself, because there was no place for it to go. So we had a lot of parties” (fig. 7).

Figure 7 Jerry Burchard, contact sheet prints, ca. 1958–59, (left) Joan Brown dancing to the Studio 13 Jass Band; (right) “Maximum Coolness”: David Park on Piano, Elmer Bischoff on Trumpet, and Wally Hedrick on Banjo Performing with the Studio 13 Jass Band at the California School of Fine Arts. Courtesy of the estate of Jerry Burchard.

Figure 7 Jerry Burchard, contact sheet prints, ca. 1958–59, (left) Joan Brown dancing to the Studio 13 Jass Band; (right) “Maximum Coolness”: David Park on Piano, Elmer Bischoff on Trumpet, and Wally Hedrick on Banjo Performing with the Studio 13 Jass Band at the California School of Fine Arts. Courtesy of the estate of Jerry Burchard.

McClure was an especially close friend and mentor to Bruce Conner, whom he met as a boy in intermediate school in Wichita, Kansas, in 1949. Eager to expand his artistic community in San Francisco, McClure wrote frequently to Conner, urging him to move to San Francisco.20 Conner and his new bride, Jean Sandstedt, moved there on September 1, 1957, immediately after their wedding ceremony in Jean’s hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska, largely because of McClure’s letters. The Conners had all their trunks shipped to 2322 Fillmore Street ahead of time and lived there with the McClures for several weeks.

Jay DeFeo recalled that Conner’s arrival was much anticipated: “For a long time there was this marvelous talk that ‘Bruce is coming, Bruce is coming.’ I used to have dreams about all these crates of Bruce Conner’s paintings coming. Honest to god dreams. And by God, one day, all these trunks came full of Bruce Conner’s paintings, preceding his own arrival. Bruce came on the scene a little bit later, in his own dramatic way, as you can well imagine.”

The young couple arrived in San Francisco eager to become part of the community at 2322 Fillmore, having already heard about the building and its occupants from McClure, Dave Haselwood, and other childhood friends from Wichita who had moved to San Francisco before them. Because there were no vacant units in the Painterland building, the Conners moved to a three-room apartment around the corner on Jackson Street, a few doors from Wallace and Shirley Berman and their son, Tosh. “One room was the studio, one room was the kitchen, and the other one was living room/bedroom, and that was it. I just didn’t have any space. I couldn’t afford to buy the space. Nobody was going to buy what I did,” Conner recalled.

Conner, despite being new to the scene, announced just months after arriving in San Francisco that he was starting a collective of sorts: “I started a group called the Rat Bastard Protective Association, sent letters out to Joan Brown and Manuel Neri and Wally Hedrick and Jay DeFeo and Art Grant and Fred Martin and a few other people I can’t remember right now. Told them that they were members of the organization and I was the founder and president, and that they should pay their dues right away. The next meeting was next Friday at my house and that we would have meetings every three weeks at a different person’s house.” As a newcomer, Conner was most likely eager to consolidate his inclusion in the community and saw the association as a way to achieve this end. He placed himself firmly at the center of this cohort of young artists by forming a group and appointing himself its president.

Conner derived the name Rat Bastard Protective Association (RBPA) by combining the name of a San Francisco trash collectors’ organization, the Scavengers Protective Association, with a slur picked up at the gym. Conner’s friend McClure, who was then the district manager of a chain of Vic Tanny gyms in San Francisco, related that his boss’s “favorite cuss word was Rat Bastard. So I picked that up, and Bruce picked that up from me.” Their meetings were held mainly at the Six Gallery, according to Manuel Neri, though many of the parties at 2322 Fillmore Street began as meetings. Conner once called for a meeting on the Golden Gate Bridge (for which only Neri showed up). “He instructed me to jump off the bridge,” Neri recalled with a laugh. Fred Martin also hosted a meeting at his apartment, Bruce and Jean Conner held one or two in their home, and another was held, in spring 1959, at the Clay Street studio of Alvin Light (1931–1980), a sculptor who moved in 1951 from his hometown of Stockton to San Francisco, to attend the California School of Fine Arts. (Light ended up spending his entire life there, first as a student and then, beginning in 1962, as a teacher.) Carlos Villa was at Light’s studio, along with “eight or nine other people,” including Bruce and Jean Conner, Joan Brown, and Manuel Neri. Light had just moved into an enormous studio, Jean Conner recalled, and he “had pieces there by Manuel Neri, or a piece, as well as his own work. [Light’s] work was very lovely woodwork, wooden sculptures. It didn’t seem to fit with the Rat Bastard work, but I guess he was part of the gang.”

Conner told the curator Peter Boswell in 1983 that the name Rat Bastard was fitting because, like the garbage collectors and the rougher types of men who frequented gyms in those years, he and his friends saw themselves as “people who were making things with the detritus of society, who themselves were ostracized or alienated from full involvement with society.” Besides Conner, the idiosyncratic group over the years included Robert “Bob” Branaman (b. 1933), Wallace Berman, Joan Brown, Jess, Jean Sandstedt Conner (b. 1933), Jay DeFeo, Art Grant (1927–1995), David Haselwood (1931–2014), Wally Hedrick, George Herms, Jess, Alvin Light, Fred Martin, McClure, Manuel Neri, and Carlos Villa, among other, less constant members.

The group played in jazz bands, ran alternative galleries, and lived, worked, and exhibited together in the Fillmore neighborhood for the better part of a decade. Conner even designed what he called the “approved seal of the Rat Bastard Protective Association,” a rubber stamp to be used by members to sign their works. Carlos Villa recalled that Conner also used the stamp to signal his approval—of just about anything. Like so much of Conner’s work, the seal was multivalent: it signaled belonging, it commodified, it spoke of hubris, and it was funny. Most of all, the stamp was designed to unify a group of artists who felt alienated from the mainstream and deprived of institutional acceptance (if only because few knew about them).

Conner himself, according to McClure, was the personification of a Rat Bastard work:

The first time I ever saw a Rat Bastard, Bruce had disappeared for several days while he got himself ready for his draft examination. Draft physical. He disappeared for, I don’t know—three, four, five days. And then, after the test, he came knocking on the door. Here was Bruce, whiskers growing in different directions, his face smeared, his clothes tattered and torn, dishevelment that would make Hamlet at his worst look like a sartorial exclusive. Bruce really looked like hell. And he had spent several days getting himself in this condition, preceding the draft examination. And he was carrying the first Rat Bastard [work] I ever saw. It looked like a canvas with a handle on it. So here he was, in this horrible ex-army jacket he had, and he was carrying this, and it had feathers sticking out, dolls heads in it, peyote buttons in it, and I said, “Bruce, what happened?” and he said “I’m out.” When I first understood what he was doing with the Rat Bastards I said, “This is the first big thing since Pollock dripped. This is the next big thing.” Not that they were assemblages but that they were Rat Bastards.

The work McClure saw Conner carrying that day was RATBASTARD (1958; fig. 11). The RBPA was a social group and an artistic alliance in equal measure. It filled an urgent need at a time when Bay Area artists were isolated from artists elsewhere in the country, lacking both galleries and serious collectors to support their artistic endeavors. Assemblage was a common denominator in the group during these early years, when their works often addressed consumerism, the drug culture, and political unrest. Few of the artists in the group achieved much national recognition during their lifetime, certainly not in comparison with the Beat poets, but their work animated broader social and artistic discussions, and over time their ideas dispersed into art movements that spread and became an accepted part of American culture.

From WELCOME TO PAINTERLAND. Used with permission of University of California Press. Copyright © 2016 by Anastasia Aukeman.