The Art (or Non-Art) of the Cinematic Dictionary Open

The Definitions that Begin 13 Films and TV Shows

On the first of February, 1884—134 years ago today—the first installment of the earliest edition of what we now know as the Oxford English Dictionary was published. In 352 pages, it covered words from A to Ant, cost 12 shillings and 6 pennies, and was officially titled A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. It sold about four thousand copies, which sounds pretty good for the time. Of course, today, the OED is ubiquitous—and as it turns out, dictionary definitions in general are also ubiquitous, not just in academic settings, but as openings for bad speeches, lead-ins for awkward presentations, and title cards for tons of movies and television shows. Which has made them pretty cliché. To quote Alison Brie’s Annie, in Community: “The “Webster’s Dictionary defines” intro is The Jim Belushi of speech openings: it accomplishes nothing, but everyone keeps on using it, and no one knows why.” I may not know why, but on the birthday of the Dictionary of Record, I have rounded up some of my favorite examples from film and television—certainly not an exhaustive list, but fun nonetheless. Add on at will below!

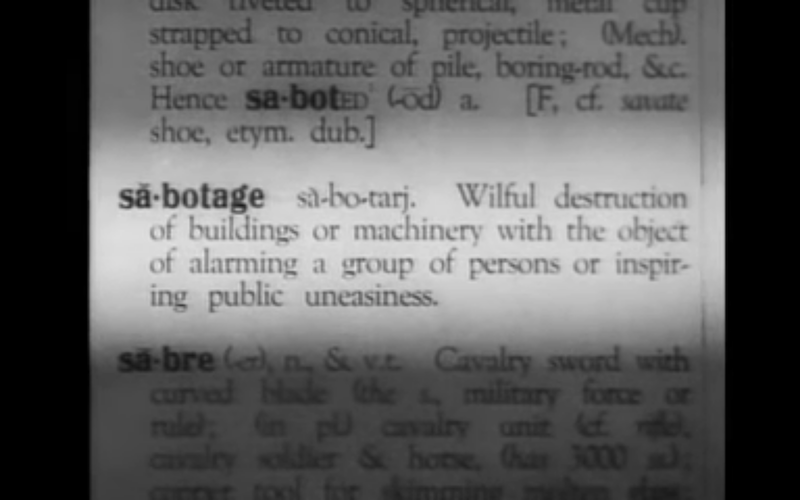

Sabotage (1936)

Sabotage (1936)

Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage is the earliest example of this trope that I could think of (which doesn’t mean that it’s actually the earliest example of this trope), and he opts for a spooky lo-fi approach: an actual filmed shot of the definition as it would appear in a dictionary, as opposed to a title card.

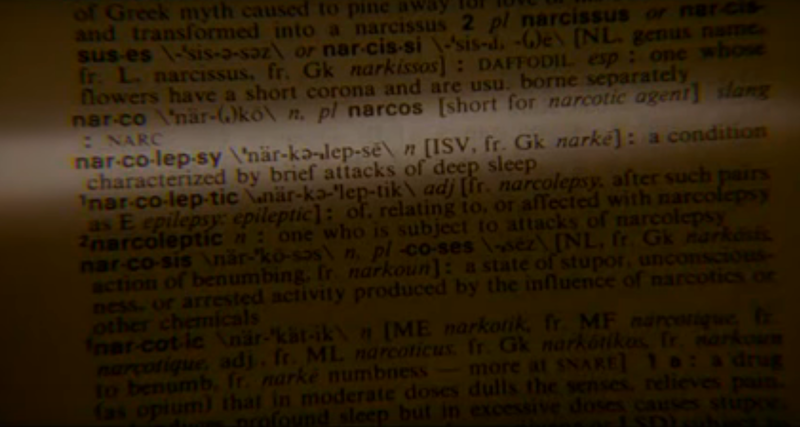

My Own Private Idaho (1991)

My Own Private Idaho (1991)

And in the opening shot of My Own Private Idaho, Gus Van Sant references Hitchcock (in addition to Shakespeare, of course) by using an actual dictionary—and even highlighting the relevant definition with a band of light, as Hitchcock does.

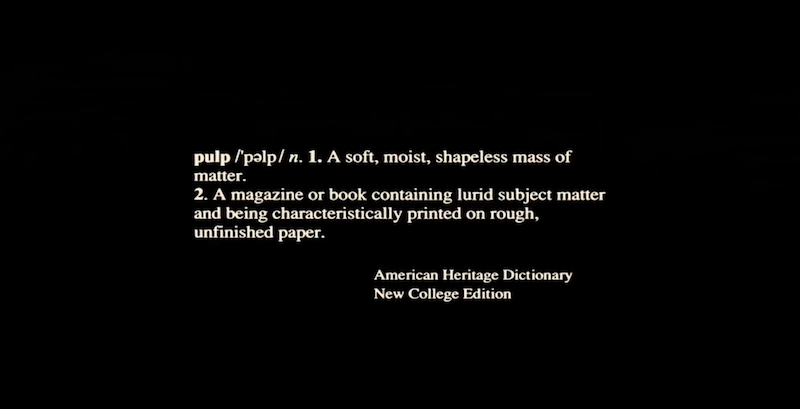

Pulp Fiction (1994)

Pulp Fiction (1994)

This is probably the example you thought of first—and it’s one of the most interesting, in that its relevance (particularly the relevance of that first definition) isn’t immediately obvious to the movie. Count on Tarantino to make a cliché into something cool.

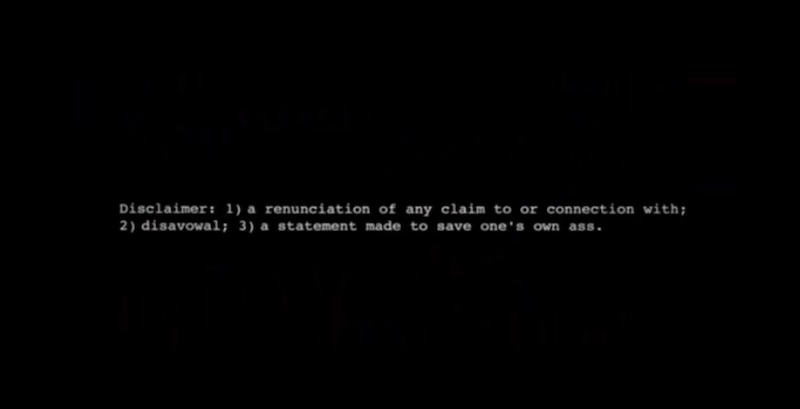

Dogma (1999)

Dogma (1999)

Dogma does not define “dogma,” but instead defines “disclaimer,” which it then immediately provides. This did not, of course, prevent the protests.

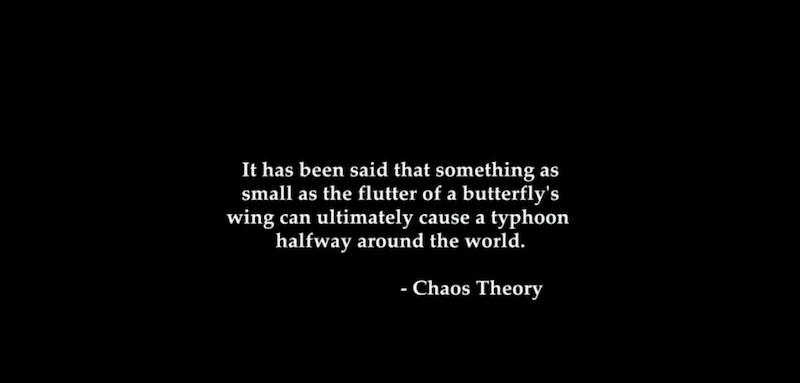

The Butterfly Effect (2004)

The Butterfly Effect (2004)

This one’s weird, because the way it’s set up it looks like a quote from someone named “Chaos Theory,” when in actuality it’s a (fairly watery) definition of chaos theory itself. I’m going over the writers’ heads to count it.

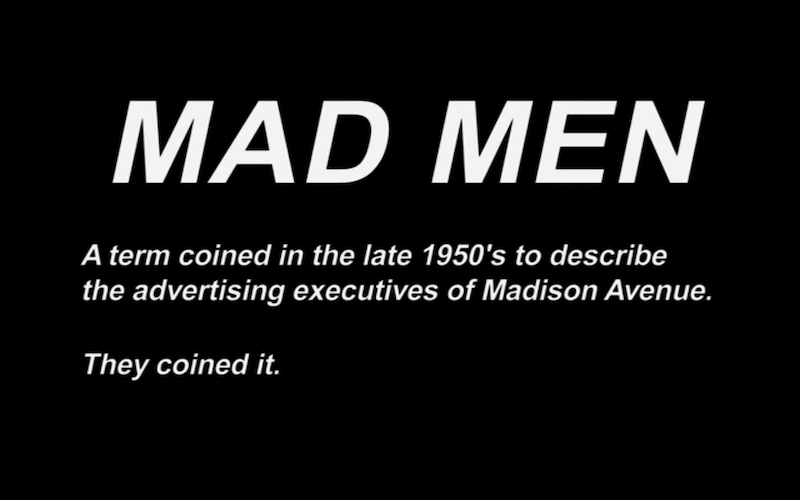

Mad Men (2007)

Mad Men (2007)

Do you remember this from the very first episode of Mad Men? Looking at it now, it’s shocking to me how devoid of style it is—very much at odds with what the show came to represent.

The Mentalist (2008)

The Mentalist (2008)

Sometimes you need multiple cards in order to get your point across. The typewriter font is cringeworthy.

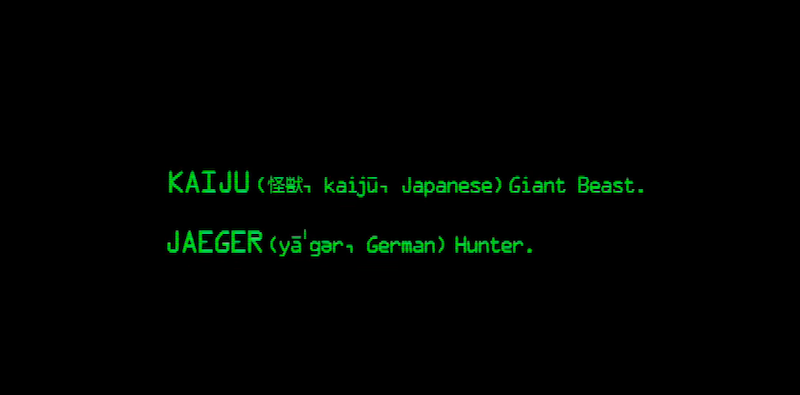

Pacific Rim (2013)

Pacific Rim (2013)

Guillermo del Toro’s monster movie opens with definitions of its two principal combatants: the giant sea monsters that have snuck onto earth via an underwater interdimensional portal to wipe out humanity, and the robots that humanity has built to fight them. Both definitions above rather undersell the creatures in question, I’d say.

Halt and Catch Fire (2014)

Halt and Catch Fire (2014)

The beginning of an underrated period piece about early computer programmers in the 1980s. The “catching fire” idea is an exaggeration, but only literally.

Dope (2015)

Dope (2015)

The rare occasion where a straight definition is also a humorous one. You knew all of these definitions for “dope,” of course—but it’s still funny to see them all next to one another.

All These Sleepless Nights (2015)

All These Sleepless Nights (2015)

This Polish movie has the distinction of offering the only definition for a phenomenon I’ve always noted but never been able to describe.

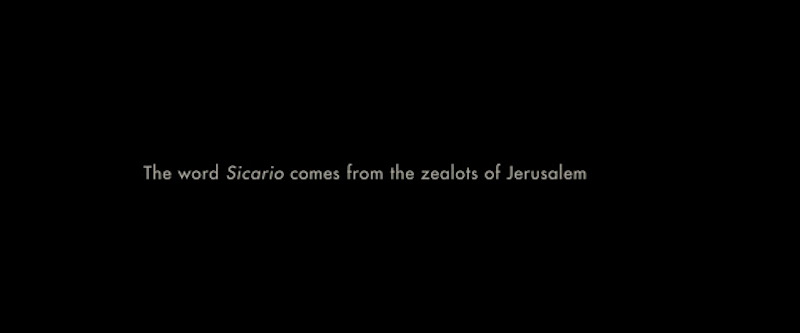

Sicario (2015)

Sicario (2015)

According to Wikipedia, the Sicarii were one of the earliest “cloak and dagger” assassins, who would sneak into crowds to stab the Romans with tiny knives hidden in their clothes—the word translates literally to “dagger-man.”

Narcos (2015)

Narcos (2015)

The next slide reads: “There is a reason magical realism was born in Colombia.” Though not everyone agrees.

Bonus: Vertigo trailer (1958)

In which there is not only the definition of “vertigo” but the dictionary opening (on its own?) to reveal it.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.