The Art of the Late Bloomer

On the 18th-Century Artist Mary Delany and the Power of Second Acts

The 18th century was a golden era for finding stuff in England: Roman coins in the garden soil, plesiosaur bones in the Dorset cliffs, passions buried under the crust of social expectations.

Among the more delightful discoveries of the age was the 1771 realization of a new art form by Mary Delany, a 72-year-old Englishwoman recovering from the grief of widowhood on an extended visit to a friend. After an inspiring meeting with Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, the botanists who accompanied Captain Cook on his journey through the South Pacific, Delany took a pair of scissors and began to cut a piece of handmade paper. The result was the first of the Flora Delanica, a collection of 985 paper mosaics of plant life so startling in their accuracy that botanists still consult them more than 200 years later.

These blossoms husbanded from the barrenness of grief were a remarkable act of creation by a woman with no formal training or credentials, apart from “eyes that had 72 years of pure noticing,” as the poet Molly Peacock writes in her luscious biography of Delany, The Paper Garden: An Artist Begins Her Life’s Work at 72.

The mosaics belong now to the British Museum. The complete collection is available to view in the museum’s online gallery or in person by appointment, and two rotating examples are on perpetual display in the museum’s Enlightenment Gallery. Designed as the personal library of King George III, the gallery has the high molded plaster ceilings and inlaid mahogany floors befitting a monarch’s place of learning. Its display cases and shelves are a menagerie of the oddities whose inspection and categorization the Enlightenment found so enlightening: ichthyosaur jaws and Greek urns, flint axes and dried blowfish.

A walk through the gallery’s aisles reveals how many of the museum’s early collections were seeded by people whose hobbies provided creativity and meaning perhaps not found in their daily roles. Gustavus Brander was a director of the Bank of England and an avid fossil hunter. Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode was a wealthy bachelor who left behind a bequest of prints, shells, fossils, and engraved gems, plus an obituary in the Gentleman’s Magazine that noted with some awe that he had never ridden a horse. The desperately poor Mary Anning sold seashells to tourists near Lyme Regis, while quietly unearthing, preparing, and classifying one of 18th-century Britain’s most important troves of paleontological discoveries.

Delany’s primary occupation, of course, was being a woman of some means, a role so all-consuming society strongly discouraged any other activity. “She lived in an age when women hid their lights,” Peacock explains, “but to hide a light means you know you have one, and it means you understand that you have to protect it from threat and nurture it for growth.”

Delany lived first through a forced teenage marriage to a grotesque, much-older landowner, then a relieved early widowhood, and then a happy union of nearly 25 years to Patrick Delany, an Irish theologian with whom she enjoyed friendship and and a mutual passion for British gardens. It was a relationship in which both parties flowered and thrived, two late bloomers (Mary was 44 at their wedding, Patrick 57) taken aback by the pleasure of one another’s company.

His death in 1768 cast a darkness. There was no model for elderly widows to find purpose or self-expression in a new medium expertly layering art and science. Mourning the end of a marriage and the loss of a kind and loving life companion, Delany’s cultivation of art from the loam of her grief was a creative act as bold as any of her blooms.

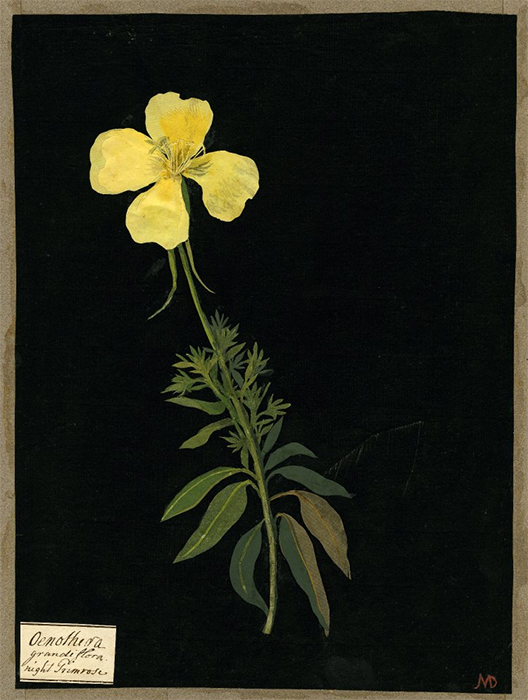

Mary Delany, Night Primrose, 1780. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Mary Delany, Night Primrose, 1780. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

I thought I’d have to look hard for them when I visited the British Museum on a late April day this year, but Delany’s flowers were just to the left of the gallery’s southerly entrance, tucked behind a bust of botanist John Ray and two cases over from the mounted, taxidermied feet of a zebra, giraffe, and rhinoceros. The glass-encased cabinet bloomed with a moss provence rose, a delicate-seeming but deceptively resilient pink blossom encased by a prickly stalk, and a night primrose, another late-blooming wonder erupting bold and yellow against an inky black background.

In person, the mosaics resemble pressed flowers more than paintings. The detail is stunning: each one a delicately overlaid assembly of as many as 200 pieces of finely cut paper, every vein and anther its own deliberate act. It was a failure of eyesight, not of imagination, that ended Delany’s artistic career in 1783. She wrote a farewell ode to her beloved blossoms and lived another five years in a cottage provided by George III, he of the elegant library and deep admiration for Delany and her work.

Unexpected flowers can have wondrously uplifting effects. I visited Delany’s blooms shortly after a period of marital metamorphosis, the kind brought about not by any single cataclysm but by the accumulation of life’s ordinary trials, like a petal collapsing suddenly under the weight of a soft summer rain.

It was one of those times in which the only viable resolutions are to break apart (the leaf falling from the branch, the brittle blossom crumbling at the touch) or to grow into something new, a form that acknowledges and accommodates the specimens you have grown to be. We chose the latter, and in the aftermath I wandered the museum exhilarated, exhausted, looking for examples of second acts of greater depth and color than the first.

“Living a full life requires invention, but that needs a previous pattern, if only to react against or, happily, to refigure in the making of something new,” Peacock tells us. It’s true in art, and in love, and in the long unfurling toward maturity that is every life’s work. A marriage is an act of constant creation, one that demands a brave and watchful eye willing to seek the shoots of new growth in the ashes of what’s been lost. We marry as two-dimensional silhouettes, opaque to one another and ourselves; over time we layer our shared joys and heartbreaks, disappointments and discoveries into figures we could never have imagined as we faced one another unseeing, into shapes that take our breath away with their depth.

A seed germinates in the detritus of plants that died before it; our earlier missteps fertilize a more mature love. There is always something new to be found.