The Art of Lying: Kate Weinberg on the Similarities Between Fibs and Fiction

“Let’s be more honest with ourselves and all those who may learn from us: about the slipperiness of truth, about the wonders of fiction.”

The first time I remember lying, by which I mean telling a real whopper, I was nine years old.

My mother had died when I was three, and my stepmother sought out a single sex boarding school that “took girls early” and had more than a whiff of the Victorian. Certain details are hazy, others are not. I think I was in my second year. I’m absolutely sure I was sitting in an English class (named, I now realize, with astonishing pomp) Anthology: A Collection of Poetry and Prose.

We were mid-class when the door opened and Miss Elder walked in. Miss Elder was my housemistress, an Australian woman with a thin, mean face and bunched lips that moved in and out even when she wasn’t speaking, like a puckering cat’s bum.

“Kate Weinberg, come with me,” she said, beckoning with a bony finger.

If you think this sounds too much like the beginning of a Roald Dahl story, you’d be forgiven. Godstowe Preparatory School was like that back then. If Miss Elder could have led me down the corridor by the ear, she would have done.

Looking back, I’m interested in the lie I told that day….It was, in other words, my first attempt at fiction.

“Your parents are waiting in my office,” she said.

This was devastating news. By “parents” she meant my father and my stepmother (who always dressed head to toe in black, and, I was pretty sure, had a few Dalmatian fur coats in her cupboard). And if they had come all the way from London to High Wycombe in the middle of the day, leaving their busy day jobs, this was Very Serious Indeed. I normally only saw them a handful of times a term, on half-term and fixed exeats. A mid-week visit was unheard of.

But it was only when Miss Elder opened the door to her study, that I realized I was truly screwed. There was my father, immaculate in a blue shirt with a crisp white collar, navy suit and red tie; and there was my stepmother, terrifyingly glamorous, with her heavily kohled-eyes and thick ivory bangles on her wrists. But far, far worse than this was the figure sitting upright in an armchair, with a rigid perm and unblinking eyes.

Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly was the headmistress of the school, a semi-mythical figure who was rarely seen anywhere apart from Morning Assemblies. At 8.15 AM every morning she would sweep into the chapel, at which point the whole school rose wordlessly to their feet, teachers included. She would walk gravely down an aisle in the middle, preceded by a few paces by an anointed girl who carried a hymn book aloft on a small velvet fringed cushion. They would both advance to a stage at the front, where the girl would place the hymn book on a table and then walk backwards to the side of the stage where she would stand with her hands placed behind her back, legs slightly akimbo like the Swiss Guard at the Vatican. Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly would take her seat in a large chair in the middle of the stage. It was covered in red velvet, with gold initials embroidered on front. EIIR. Elizabeth The Second Reigns.

“Good morning, girls,” said Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly.

“Good morning, Miss Fitz-Maurice Kelly,” chorused the upstanding girls in lilting unison.

And you begin to see it now, the pickle I was in. There they all were, sitting waiting for me in Miss Elder’s study. Miss Elder, my father, my stepmother and Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly; all staring at me like the board of disapproving nuns at the beginning of The Sound of Music.

“Do you know why you’re here?” asked Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly.

I shook my head. It was true. I didn’t. I was a naughty child, given to causing a ruckus after lights out, doing impressions of teachers behind their backs and teaching other kids swear words I’d learned in summer camps. It could have been anything.

“It’s been brought to one’s attention that you told a disgusting story that you seemed to think was a joke. We have been minded to expel you. But I have discussed matters with your parents and we are going to give you a choice. Either you pack your bags now, leave with your parents and never come back. Or you tell us the whole story, word for word.”

“You mean, tell you…the joke?” I faltered.

Miss Fitz-Maurice Kelly gave me a short sharp nod. Her perm would not move, I reckoned, if she went sky-diving.

I looked back at the board of nuns. The cat’s bum was puckering at alarming speed. The true horror of my situation began to sink in.

It still pains me to relate the joke now, as an adult. Partly because I can remember the terror of the stifling weight of silence in that room. But also because of the extreme awfulness of the joke. Which was, I’ll make this fast, a story about a woman who lost her beloved husband Charles in a car accident, sliced off his dick and mounted it on the wall, so she could still have sex with it every night. An opportunistic stranger spotting the routine, cut a hole in the wall and swapped his dick for the dead man’s. A few weeks later a woman walked in with a carving knife and announced, “Come on Charles, we’re moving house.”

Like I said, not a humdinger.

I don’t how long it took me to open my mouth and tell the joke. Possibly it wasn’t the seventeen hours it felt like. I do remember trying to swap out some words to make it less damning. I used “willy” instead of “dick.” I described how “every night she battled away” to avoid saying “sex.” None of the assembled group found it funny. If my father’s lips twitched, I didn’t see it.

We would like to know who told you this filthy story, said Miss Fitz-Maurice Kelly when I’d finished.

I stared at my headmistress.

She stared back at me with her pale-lashed eyes.

“A girl in Summer camp,” I said eventually.

Children spend a lot of time crossing the line between reality and fantasy….Let’s not pretend to our children or each other we have a lock on “the truth.”

And I then went on to describe the girl in detail. Red hair with a fringe. Freckles. Braces: not railway tracks, the upper-teeth plate that you took out for meals. Nail varnish that was black and green on alternate fingers. The bully of the camp. I’d heard her father was a criminal, so maybe that was why. He was in prison, I added. For stealing race horses.

It hadn’t occurred to me to lie about what the joke was. I guess I assumed whoever had sneaked on me (we slept in dormitories of six, but the matrons were also spies) had also relayed the story. But I knew I wouldn’t snitch on the girl who had actually told me the joke. She was at school, in my year. Another troublemaker.

Looking back, I’m interested in the lie I told that day. I’d lied plenty before that, self-serving childhood fibs: blaming siblings, cheating at board games. In a family of six children, it was survival of the fittest. But this was quite a different order. I gave the imagined girl a very distinct, detailed appearance, a back story that might tally with her behavior. It was, in other words, my first attempt at fiction. It made me feel awful.

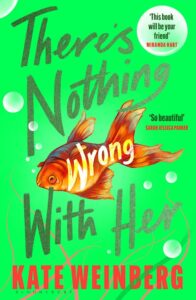

They say Eskimos have lots of different words for “snow.” I wish there were as many for “lying.” Because I would have loved to tell that frightened, shamed girl sitting in the oppressive silence of that room, imbibing the thick disapproval in the air and believing that she was, to quote Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly, a “corrupting presence”—that what she did that day wasn’t so bad at all (although the joke was lousy). That coming up with an imaginary culprit may have been a lie, but it was also creative and kind, and that one day she would turn into a novelist, who would make up things every day, and give people pleasure from it. And moreover, she would explore lying in her work, she would make her main character also tell a whopper that was far more outrageous and disastrously consequential, but creative and kind and morally interesting, too.

Children spend a lot of time crossing the line between reality and fantasy. We urge them to, when we foist story books and movies on them, tell them that Father Christmas and the Tooth Fairy arrive for good children, give them the impression that as adults, we know the rules, have it all under control.

Let’s not pretend to our children or each other we have a lock on “the truth.” That like Miss Fitz-Maurice-Kelly we are sitting on some stage, reveling in our authority, and dispensing judgement from our made-up thrones. Let’s be more honest with ourselves and all those who may learn from us: about the slipperiness of truth, about the wonders of fiction.

__________________________________

There’s Nothing Wrong with Her by Kate Weinberg is available from Bloomsbury UK.

Kate Weinberg

Kate Weinberg was born and lives in London. She studied English at Oxford and creative writing in East Anglia and is the author of The Truants. She has worked as a slush pile reader, a bookshop assistant, a journalist and a ghost writer.