The bus route down from the Medellín airport doesn’t make you nauseous like it used to, not like when you were last driven on it twenty years ago, an eight-year-old girl on her way to Heathrow. Now you’re twenty-eight and the road is still one sharp curved turn after another, past restaurants with names like Sancho Paisa and trashy nightclubs like Oh My Sweet Jesus. Grinning statues of machete-wielding farmers, Texaco gas station stars. PANADERÍA signs on every corner, scraggly half-dead grass on the side of the highway. And down there in the valley below is the city—your city—its far-off lights lurking like tiny star clusters from a distant galaxy, awaiting your arrival.

When you get off the bus at the Sandiego mall, a girl in a collared shirt heaves your suitcase into the front seat of a cab, paying no mind to your apologetic warning of Careful, it’s very heavy. You overtip her out of nervousness and she bows her head: —Thank you, miss. The taxi driver gets lost and keeps refusing to go down the street you insist is correct, based on the directions saved on your phone. —I really think it’s this way, you say, as he turns the steering wheel in the opposite direction of where you’re pointing.

By the time the driver has managed to lurch your suitcase onto the pavement, a man has come out of the building. He stands at an awkward distance, arms crossed, like he doesn’t want to get too close. You pay the taxi driver in exact change and he says, —Thank you, beautiful.

When the taxi finally drives off it feels like the man has been standing there an uncomfortably long time. His head is shaved close to the scalp and he’s wearing a long-sleeved white shirt that hangs past his wrists and white exercise sweatpants with a black line running down the sides. Even his tennis shoes are white: a clean white, like they’ve just been purchased. He could be an assistant football coach, or a sports-shoe salesman.

—. . . Matty? you say.

But the man shakes his head. —He’s not here, he says. He should be back soon. But he told us you were coming. Don’t worry, he left very specific instructions.

—Instructions, you say.

—That’s correct.

A shudder jolts through your torso but you’re able to restrain yourself: hopefully it looks more like a twitch, rather than a violent spasm. An unexpectedly chill breeze makes you grateful for your tights, impulsively purchased at the last minute from Terminal 3’s Boots pharmacy. One of the few memories you have left of Medellín (cradled close to your body, carefully, like you’re carrying a basket of eggs) is the temperate weather. Welcome to the City of Eternal Spring—that’s what the pilot said on the loudspeaker. But you don’t recall Medellín being this cool in the evening.

The man reaches for your suitcase. —This is embarrassing, he says, but I didn’t grab my keys. We’ll have to knock hard and hope somebody’s listening.

His shirtsleeve has risen up his arm. On the back of his hand, you see what looks like scar tissue: puckered wrinkled holes, lumpy like the bark of a tree.

—No problem, you say. Totally fine. (Apparently you’ve turned into a US cheerleader, all optimistic pep talk.)

—Or I’ll tell you what, he says. Are you hungry? Do you want to go get a drink? Let’s take the suitcase and come right back.

—Um, you say. You look down the road. An old woman has come out of a building and is placing a fat garbage bag by a tree. It all seems domestic enough. Sure, you say. Why not.

Your suitcase makes a terrible rasping sound every time it goes over a crack in the pavement. He walks quickly despite dragging your suitcase along and doesn’t seem bothered when it sways dangerously after going over a ledge. Following him down the street, like a duckling trailing after its mother, you tell him about airport security. When you’d sent your suitcase through the conveyor belt, the lady looking at the X-ray screen had furrowed her brow. She’d leaned to the left, Tower of Pisa style, and tried to catch your eye.

Did you pack boxes in here? she’d asked. Dozens of them?

Making a rectangular shape with her hands.

—Books, you tell the man now as he pauses by the traffic lights. I brought too many books with me. I’m sorry it’s so heavy.

—I’d never expect a woman’s suitcase to not be, he says. Watch out, here come the motos.

An army of helmeted figures on motorcycles buzz by, an angry swarm. You take a step back, swallowing hard. You hope you’re not standing inappropriately close to him. He has a strong smell of BO, a musky scent you never encounter in London, not even in the sweatiest, swampiest hours on the Tube. Why is being back in Colombia a reminder that you have a physical body, that it’s an actual thing existing in space?

—Those motos sound like insects, you say. From a monster movie.

He makes a face as though what you’ve said is very strange and he needs to struggle to understand it.

—If you ever get lost, he says, tell the taxi driver to take you to the Anthill headquarters. Tell him Circular, and then these numbers . . .

—I know, you say. I have the address. (You don’t add How else would I have got here?)

—Or, he says, just tell them, “The Anthill headquarters, please.” If you’re anywhere near this neighborhood they’ll know exactly what you mean.

You nod, refraining from thanking him, the most tepid of feminist victories.

—I don’t mean to be condescending, he says, suitcase wobbling wildly as he steps off the pavement. I just want you to be safe. Mattías would kill me if I didn’t protect you. Like, literally kill me.

He makes a gesture across his stomach, velociraptor-claw style. On your face: the slowest of smiles.

—Would he, now, you say, and the feeling of gratitude spreading through your stomach is like something warm get- ting spilled.

Why is being back in Colombia a reminder that you have a physical body, that it’s an actual thing existing in space?

The restaurant is comida pacífica, food from the coast. He orders you a portion of fried fish, which seems a bit heavy for this time of night, but since no one has brought you a menu it feels fussy to request one. For himself, he orders a plate with all the sides (plantain, cabbage, coconut rice) but nothing else.

—I don’t eat animals, he says, moving his knife and fork out of the way as the waitress sets down a basket full of popcorn. But I ordered you ocean fish. Not river. Whenever you can, get ocean.

—Aren’t we a bit far from the ocean?

—Not at all. He shoves a handful of popcorn into his mouth. The owners of this place, their family lives in Chocó. They ship it here direct in special ice containers. Trust me, whenever you can, avoid fish from the river. No tilapia or carp ever; it’s bad for the environment. Have you ever been to the Pacific coast?

—No. I never had the chance to travel when I lived here.

—You didn’t? the man says, tilting his head in the universal manner that signifies Tell me more.

You tell him the basics, speed-dating style. Your Colombian mother, killed in a traffic accident when you were eight. Your British father, a lawyer who sent you to English boarding school. He followed you to England soon after, moving back into his family home in the south-west. He’s still living there—at least, you haven’t heard otherwise.

—Does it look the way you remember it? the man says, taking the beers directly from the waitress before she has a chance to set them down. Medellín, I mean.

—I have a really bad memory, you say, raising the bottle to your lips. I was only eight when I left.

The man nods, as if this is acceptable. He starts talking about himself. In the time it takes you to need a second round of beers, you learn his name is Lalo, he’s a freelance writer, he just came back from a three-week camping trip on the Pacific coast of Chocó, and he’s been volunteering at the Anthill since the day it opened, over three years ago.

—Working at the Anthill saved my life, he says, as you use your tongue to poke at a popcorn kernel stuck in your molar. It did! I would have been lost without it! But remind me again—how is it you know Mattías?

You pinch at the flap of skin beside your thumb, then your index finger, descending down your hand like a musical scale. If you pinch hard enough, you can almost feel the redness. —We grew up together, you say. We lived in the same house when we were kids. (You almost don’t say it, but then go ahead anyway, brutally, like it’s nothing.) We were best friends. Why . . . What did Mattías say about me?

—Exactly that, Lalo says, rotating his beer so that the logo faces him. He said exactly that. How lovely the two of you were able to get back in touch. Did he contact you first? Or—

—No, you say quickly. I, ah, got his email. From a mutual friend.

Lalo picks at the label on his bottle. —Mattías always talks about your father—how he’s been a great friend of the Anthill and all that. Financially, I mean.

This is news to you. —He has?

—Of course! He’s even said that if it weren’t for your father’s contributions, the Anthill wouldn’t exist. Mattías went to so many people! He must have raised around twenty thousand dollars in the beginning! He’s very grateful to your father, obviously.

—Grateful, you echo. Of course.

When the waitress asks if you’d like another drink, you don’t even let her finish the sentence before blurting out, —Yes.

As you push the slice of lime down the bottle’s neck, Lalo gives you the basic lowdown about the Anthill. —The Anthill children come every day, he says, the lime fizzing in your beer. Five days a week. Fridays are different; that’s when we serve Community Meal. We offer all kinds of classes: art, sports, English, computers for the teens. We only have three computers, unfortunately. How long are you in Medellín for? Will you be staying here your whole trip? You could teach English. Or anything you want, really.

—I don’t exactly have a plan, you say, not mentioning your one-way ticket, purchased with your associate tutor stipend. I just thought it’d be good to come back for a bit. It’s been so long.

—Will you be working on anything while you’re here?

—What do you mean?

He drums his fingers on the table. —Like on a book, or something.

—Oh, I’m not a writer.

—Oh!

He sits there, looking at you. So you say, —I study literature. And teach it, I guess.

A young man carrying a stack of CDs approaches the table. He says he’s from Venezuela, that this is a rap single he wrote and recorded himself, that he’d appreciate any help you’re able to provide, God willing. Lalo gives him a crumpled-up bill, you give him a coin, but neither of you accepts a CD. After he leaves, Lalo says, —A lot of people are coming to Medellín these days to be writers. A lot of volunteers. I’m working on a book about Medellín myself, actually. You wouldn’t be alone! You shake your head. You almost don’t say it, then go ahead anyway, in a rush of beer-induced honesty: —I used to want to be a writer. When I was a kid, I mean.

He nods as if satisfied, not asking for more details.

The food comes out shortly: beautifully curved mountains of coconut rice and thinly sliced cabbage. A giant fried plantain, flattened like an ancient cowpat, takes up most of the plate.

—Delicious, Lalo says, leaning over with his knife and lifting the bones from your fish in one swift motion. I never ate food like this growing up. With everything so beautifully laid out. So well arranged. Back in the orphanage, they used to serve us leftovers all mixed together. Tuna, cucumber, chorizo, watermelon, white rice, the works. I’m not kidding! What’s this, I’d sometimes ask, if I was feeling brave. But the answer was always the same: You’re going to eat it, they’d say, and you’re going to be thankful. So there we’d be, sadly scooping our spoons in and out, like builders forced to eat their own cement mix.

You can’t help but laugh at how sheepish he looks, like a puckish small boy about to start trouble. —To me, you say, that’s basically child abuse. If someone fucks with my food, they’re done for.

He smiles with his mouth closed. —The orphanage was a wonderful place, he says. They took very good care of me. I’d have been lost without it. But it’s funny how as a child everything is so mixed-up all the time, isn’t it? You don’t get any say in the matter. It’s much better being an adult.

—I dunno. Taxes . . . groceries . . .

You don’t say, Some days I can barely do my laundry. Or, Let alone return overdue library books. Forget about responding to gently concerned emails.

He takes a long swig of beer. —I suppose I can never show you my room now. You’ll see my unmade bed and scream. You smile back. —How long were you in the orphanage?

He shakes his head. —No, no. Please, you first: where did you grow up after you left Medellín? What happened? Where did you go?

So you tell him in more detail, third-date level sharing rather than speed dating: living in that English boarding school. Twenty years ago in a cold northern city. You didn’t know how to use the microwave, you loathed the taste of tea with milk, you’d never made your own bed and plantain chips were nowhere to be seen. The other international students were from Mumbai and Hong Kong, Beijing and Singapore. A boy from Dubai nicknamed you Paula Escobar; the girls invented the rumor that your feet had dandruff, due to the smears of bicarbonate of soda still left in your shoes. One of the few physical traces of Medellín you’d managed to bring with you, all the way across the Atlantic Ocean. Apparently, in England, nobody’s feet ever stank or grew sweaty.

But as the white traces in your shoes gradually faded, so did that initial feeling, in the following weeks, months, years (and this is the part you don’t say to Lalo, your voice slowly trailing to a halt). Junior school, senior school, uni. Twenty years in England—can you really call yourself Colombian anymore? Isn’t it ultimately a bit pathetic, a bit petty, clinging to those first eight years as a desperate marker of—whatever it is? God knows where your Colombian passport is, if it ever existed at all. And then there’s the weight of the money—your father’s family money—fat in the bank account, heavier and more real than anything else. British money is solid; it’s straight-forward; it makes things happen and makes things possible; while Colombia is a vague weightless ghost you occasionally invoke as a wispy spell that proves—what? In pubs, you’ve often talked about Colombia in a deeply amused voice, rattling off the blandly standard details from any upper-class Third World childhood (or were you technically middle-class, compared to the other children whose families owned islands and helicopters and horse farms?). How, as a child, you never rode in a bus or a taxi. You grew up with maids and security guards in the apartment. Instead of fire drills your school had kidnapping drills. Etc., etc.

Twenty years in England—can you really call yourself Colombian anymore?

Sometimes your audience have asked questions. Other times they’ve laughed uneasily. More often than not, they’ve sipped their drinks and eyed you. Wow, they’ve occasionally ventured. You don’t sound Colombian . . . like, at all.

It was a long slow lesson, but you learned it eventually: how there’s something undeniably a bit . . . off about you.

Something embarrassing.

Maybe you’re just kind of privileged and oblivious. Maybe you’re just plain sad. Whatever it is, it’s definitely something to be ashamed of. Deep inside you, rotting away.

And if there’s one thing ten years of boarding school, three years of uni and never-ending years of postgraduate studies have taught you, it’s that there’s nothing you can ever do to hide it.

But what you do end up telling Lalo is how awkward it was—back in boarding school, when you’d open the door and someone else would do the exact same thing across the hall, so you were left staring at each other. —Sometimes, you say, picking at your napkin, I would immediately turn to the wall and press my ear against it, like I’d heard an awful noise. Just to avoid making eye contact. Sometimes I’d even mutter to myself.

—Brilliant, he says, dropping a forkful of rice into his lap. If I’d seen that, I would have run back inside. You wouldn’t have seen me for the rest of the term!

Speaking of eye contact, his is intense: unwavering, unblinking. Like two Jedi swords jabbing at you. Enlarged red bumps dot the side of his shaved skull, like buttons on a weapon suitable for space warfare.

It takes some getting used to, but in terms of dinner conversation, there’s something enjoyable about Lalo’s dazed flitting from one topic to another. —We’ve been doing very well at the Anthill in terms of attendance, he says, holding the plantain to his mouth like a harmonica. But we need to expand. Dance classes, music. Financial literacy for the mothers. It’s very important that the Anthill continues to support the community, to establish the values the neighborhood needs during these uncertain times. The country is going through an interesting transition at the moment, as I’m sure you know. Have you ever had a boyfriend?

—Sure, you say, not missing a beat. You tell him about Dan Crawley, second year of uni. Dan Crawley was famous for playing sports you never quite understood, mysterious activities like hockey and cricket. You asked him once if he could give you a “love bite” (you say this in English awkwardly, not knowing the Spanish translation), because you’d seen so many girls sporting them in your creative writing work- shops—it had seemed like a badge of pride at the time, some weird initiation ritual.

—“Love bite?” he says, repeating the English phrase.

—Like a bruise, you say, touching his neck, close to the collarbone. You give it to someone by sucking. I think it’s also called a “hickey?”

There’s a flicker of a second where it could go a variety of ways: he could smile nervously. He could look confused. He could even recoil, thereby justifying the sudden tension coiling up in your stomach of Oh fuck, I’ve gone and done it again. But what he does is laugh and clap his hands. —“Hickey,” he says in English, in a surprisingly clear accent. I used to do that when I was a kid: make giant bruises on my arm. Here, here and here, he says, lightly touching the back of your wrist, the centre of your forearm, the crease of your elbow. I once made a really big one there, he says, placing his hand on your shoulder. It looked like Africa. When a schoolteacher saw it, he asked if the orphanage staff were beating me. He laughs again.

—Did it hurt?

His gaze flickers briefly to a man walking by, selling bouquets of wilted roses. Your shoulder feels cold when he takes his hand away. —Only when I touched it.

By the fourth beer the food has long since been cleared from the table. Even the crumpled-up wrappers from the coconut candies are gone. You reach inside your handbag and touch your box of cigarettes, but it doesn’t seem appropriate to whip one out and pronounce your identity as a smoker, not yet.

—Oh God, he says, his phone whistling like a bird. He turns it face down on the table. I’m so sorry; I have no control over that. This guy from Spain, he was an Anthill volunteer a few months ago. He’s always sending me pornography videos on WhatsApp. He’s crazy!

—Pornography?

—Exactly. Exactly! His wife would go crazy if she knew! And it’s not just to me, either—there’s like nine other people in the chat group. Women, even! Gringas like you. God, we used to get so many volunteers from Europe. We haven’t had one for ages. Gringos are much more interested in Colombia than Europeans, don’t you think?

—I’m not from the US, you say. I’m not a gringa. But he picks up his phone and taps at the screen, like he hasn’t heard.

—Can I ask you something? he says, slipping the phone back into his pocket. What did you call me, back there on the pavement? When you first saw me?

—Huh? You’re suddenly aware of that popcorn kernel again, still stuck in your upper molar. Oh. I said “Matty.” He’s . . . It’s what I called Mattías when we were kids.

—Did you? That’s very interesting, he says, as if speaking to himself. And I’m sorry, what do you go by again?

You pick up your napkin. You’ve shredded it into pieces so ragged, they’d barely serve as mummy bandages. —My full name is María Carolina, you say, but everyone calls me Carolina. (In England, you’re actually often referred to as Caroline, but you rarely bother to correct people.)

—So what should I call you, then?

He’s leaning forward, pressing his torso against the table. Hands tensed like claws.

—You can call me whatever you want.

—I’ll be honest with you, he says. With so many volunteers coming and going from the Anthill, it becomes hard for me to tell them apart. In my head they tend to all be the same—the new volunteer.

He laughs but his hands are still tensed, fingers stiff. His shirtsleeve has risen up, exposing those puckered-lip scars.

You scrunch the napkin into a tight ball. —If you like, you can call me Lina.

—What?

He says it so sharply, you can’t help but sound defensive.

—It’s what Mattías used to call me! Or at least . . . that’s what I remember.

He leans back into his chair. Away from the table, away from you. —He doesn’t.

A motorcycle screeches to an abrupt stop behind you; your heart jumps against the bones of your chest, a startled caged animal. —Doesn’t what?

—Remember. Lalo rises to his feet. Excuse me, with your permission.

He heads to the back of the restaurant. While he’s gone, a woman with acne offers to sell you a plastic bag full of nuts, which you accept. A few tables away, an old man with a tiny black dog in his lap raises his glass and throws ice over his shoulder, scattering it all over the street.

—Let’s go, Lalo says, appearing at your side. It’s getting late.

—But the bill?

—I took care of it, don’t worry. He touches you on the elbow as you stand up. Listen, I wanted to ask you something: did you really mean it earlier, what you said about teaching some classes?

He wraps his fingers around the beer bottles’ slender necks, lining them up at the table’s edge.

You don’t recall saying you were willing to teach anything. But he keeps talking: —Because it would be a great help to us. We’d truly appreciate it. I know Mattías would too.

—What kind of classes?

—Whatever you want. English, if that’s easiest. You make a face.

He smacks his hand against his forehead, as if this reaction of yours is unbearable, intolerable. —No, forget that, forget I even suggested it! God, Lalo, so stupid of you! What an idiot! I know what you can do, he says, wagging a finger. You can run Leadership Club.

—Leadership? (It seems you’ve moved on from only expressing yourself via cheerleader-speak to high-pitched questions.)

—It’ll be easy, he says. Trust me. We’ve chosen specific children to participate, the ones who’ll benefit the most. Kids who are well behaved and get along with others.

—It all sounds a bit vague.

—That’s because it is. Mattías runs it, you see.

When he says Mattías’s name this time, you have to swallow hard: rising warm liquid, the taste in your mouth you get when you’re carsick.

Lalo says quickly, —But he’ll be much happier if you run it instead! Especially if doing it makes you happy.

—Is that true?

Lalo nods fervently.

Mattías: happy that you’re happy.

—Okay, you say. Sure. Leadership Club it is. I’m not good with kids, though.

He lines up the last beer bottle, clinking its belly against its companions. —But I thought you were a writer?

—Pardon?

—Teacher! He smacks his forehead again. Sorry, sorry. Lalo, you dummy, ugh! I meant to say: you’re a teacher, correct?

You think about it: the first-year undergrads you taught last term. Sixty-plus essays about Roland Barthes. You submitted your marks three days late and never responded to any of the module leader’s increasingly frenzied emails. Your student evaluations contained comments like The tutor did not seem to know what she was doing and This class was more of a book club than a seminar.

—Yeah, you say. I’m a teacher. Sure.

—“Piece of cake,” he says in English, surprising you again with his perfect accent. You can pay the volunteer fee tomorrow. We ask everyone for a one-time contribution, the equivalent of sixty US dollars. I’ll take you to the cash machine first thing, no problem. Shall we go to the bar?

You look at the row of beer bottles: it would be so easy, saying Yes. But instead you say (in an untypical demonstration of non-alcoholic restraint), —I should probably go to bed.

—Of course, he says. I didn’t mean to pressure you.

—No, no. Next time, I promise.

He claps his hands, as if sealing the deal.

On the walk back, the two of you pass a Virgin Mary statue on a squat cement block, her hands broken off. —A paramilitary victim, Lalo says, pointing at her granite stumps, but you don’t laugh. A flying cockroach buzzes past, brushing your arm.

—Jesus, you say, stopping in your tracks. Isn’t that lovely. He turns and karate-kicks the roach against the cement.

You can’t help but scream in surprise at how fast he’s moved, the explosion of noise, the roach’s little brown body smashed against the statue’s base.

—That’s how you do it, he says, straightening his shirt. That’s how you clean this place up.

You glance over your shoulder as you walk away. The roach has left a dark smear under the Virgin’s feet.

—You need to be careful in this city, he says, resting his hand briefly on a telephone pole. Especially you, with skin like that. I wouldn’t carry your iPhone around if I were you. And forget about putting in earbuds.

He starts crossing the street in long strides, his sweatpants swishing. You follow, your enormous suitcase squeaking behind you, which he didn’t offer to take this time.

—Medellín has changed a lot in the past few years, he says. As I’m sure you know. Oh, it’s safer now, for sure. It’s a bit of a tired narrative, to be honest, about how the city has transformed and all that. Everybody loves a nice renewal story, no? But war is not something good; on that we can all agree. And there’s nothing better than having a quiet life with your family and living in peace. Who wouldn’t want that, right? But to me (he says, quickening his stride), if this country knew the truth of what’s going on—about what happened to its neighborhoods, what’s still happening—the truth would make it fall apart. So when you’re walking around this city (he says, not looking at you as he speaks), when you’re looking at this person or that one, you won’t be able to recognize who was once a guerrilla or who was once a paramilitary. Who was bad or who was good. It’s like when you put something in the trash: it instantly becomes garbage. And it doesn’t matter if it used to be this thing or that thing, for the kitchen or the bathroom, used once and discarded or held on to for years and genuinely loved by someone, genuinely adored. Once they put you in the trash (he says, staring straight ahead, as though his eyesight is an intense beacon you both need to light the path ahead), you’re rotten. That’s just the way it is.

As the two of you approach the Anthill headquarters, he pulls a ring of silvery keys out of his pocket.

—Don’t kill me, he says, but I had them all along. I should have checked my pockets more carefully. What a dummy I am, right?

—Ha, you say. You clutch the handle of your suitcase, looking vaguely around. More trash bags have been brought out, propped against the trees like freshly laid eggs. There’s a bottle of duty-free whisky in your suitcase—should you invite him into your room to keep drinking? Would that be weird? Would it be even weirder (not to mention somewhat pathetic) if you just kept the party going by yourself?

The keys rattle in his hands as he raises them towards the lock. —I have something else to tell you, he says, but you have to promise not to kill me. Promise?

—What? you say. It feels like the conversation is getting away from you, escaping, like a balloon sputtering around the room. Maybe the jetlag is kicking in but you suddenly feel very, very tired. Okay, you say. I promise.

—It’s Mattías, he says. It’s me.

__________________________________

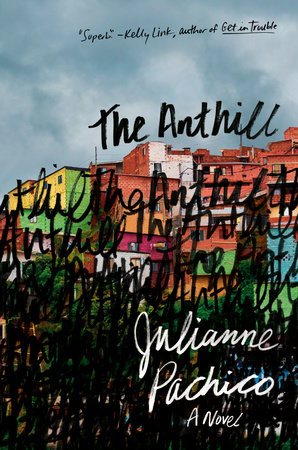

Excerpted from The Anthill by Julianne Pachico. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Doubleday.